In the 1916 Democratic primary—the first legal primary held in the state—Thomas W. Bickett soundly defeated his opponent, lieutenant governor Elijah L. Daughtridge.1 With his party’s nomination secured, Bickett then set his sights on the general election, in which he would face Republican nominee Frank A. Linney. Linney focused his campaign on Democratic corruption and mismanagement, citing financial irregularities in recent state audits and the deplorable conditions of the Confederate Soldiers’ Home. Democrats took criticisms of the latter right on the chin, the press largely printing the damning reports of overwhelming fly, bed bug, and cockroach infestations then plaguing the home and its residents.2

In return, state Democrats branded Republicans as unpatriotic, corrupt, and eager to destabilize white supremacy, stoking racial fears at every possible turn. At the Democratic state convention in April 1916, United States Senator from North Carolina Furnifold M. Simmons decried the Republican Party as an “alien horde” that “burdened the state with debt, disgraced it with scandal and degraded it with negro rule.”3 Future Democratic governor Cameron Morrison urged voters in Guilford County to remain vigilant and steadfast. Any lapse in their support, he warned, would result in a return to “mongrelism, negro rule and incompetency.”4 In a widely circulated letter, state Democratic Party chairman Thomas D. Warren equated a Republican victory with the “restoration of Negro suffrage” and the institution of “Negro rule.”5

Campaign button bearing Thomas W. Bickett's likeness, name, and campaign slogan, circa 1916. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Governor Thomas W. Bickett delivers a speech at the Esmeralda Inn in Chimney Rock on July 4, 1918. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

For the most part, Bickett steered clear of race-baiting politicking, allowing Democratic peers to lead these kinds of craven attacks. In campaign speeches and public addresses, he chose instead to closely align himself with the policies of the Wilson administration, centering his talking points on foreign policy, the war, and domestic peace and prosperity.6 At every turn, he refrained from openly criticizing state Republicans and appealed to populist and progressive sympathizers—those who had helped install Republican politicians in 1896 and 1912, specifically—imploring them to return to the Democratic Party: “In the name of the family that has missed you I extend to you an invitation to come back to the old homestead. You are essentially of Democratic lineage.... Our doors swing wide to receive you.”7

If the politically centrist tone of his campaign wasn’t enough to convince fallen Democrats and moderate Republicans, Bickett could always rely upon his personable and affable nature to win voters’ hearts. Across the state, Bickett’s audiences could not help but fall in love with his keen wit, charm, and able storytelling, tools that he used to his advantage again and again. At Lexington on October 3rd, 1916, the many days of travel and long speeches began to catch up with him. With a “crippled voice,” Bickett began his address to the assembled crowd “slowly and deliberately” but eventually picked up speed and “soon had the audience roaring with laughter…or hanging almost breathless to catch [his] every word.”8 It was a scene that played out at campaign stops throughout the state. He was nothing if not a great speaker.

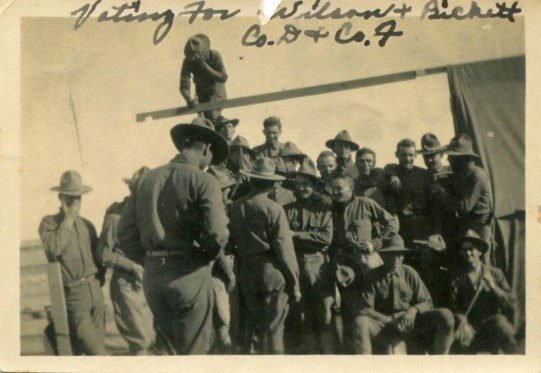

Support for the Democrat’s campaign was enthusiastic. Wilson-Bickett Clubs organized across North Carolina, in towns large and small, arranging speeches, rallies, barbecues, and voter registration drives. Club members in New Bern fabricated and displayed campaign signs riffing on Wilson’s reelection campaign slogan, a nod to the nation’s isolationist stance towards the war: “America First, vote for Wilson and Bickett.”9 On “Wilson Day”—October 28, 1916, ten days before election day—the clubs made one last push for the Democratic ticket, holding rallies to promote and celebrate Democratic gains made since the turn of the century.

On election day 1916, more than 167,000 eligible voters10—which included few men of color and no women—cast their ballots for Bickett, handing him the governorship by a margin of more than 46,000 votes.11 Linney humbly conceded, and Bickett accepted with grace:12

Members of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry cast ballots in the 1916 election while stationed at Camp Stewart near El Paso, Texas. Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina.

Bickett’s victory ensured the fulfillment of the state’s Democratic Party platform as it stood in 1916: support for the good roads movement, improvements in public health, continued development of public education, recruitment of new businesses and capital investments for job creation, and increased support for agriculture and the rural communities that relied upon it.13

Democratic triumph additionally guaranteed—in explicit terms, no less—the continuation of white supremacy. “So long as the Democratic Party is in power,” the platform promised, “the people have assurance that this State shall be conducted by white men….” Strict, racially-motivated voting laws, established by a state constitutional amendment passed in 1900, stripped most Black men of the franchise. Sixteen years after its passage, Democrats doubled down on the measure, reaffirming their “confidence in the wisdom and justice of the suffrage amendment."14

Over the next four years, Bickett walked a fine line between progressivism and conservatism, championing advancements for the people of North Carolina while also maintaining well-established societal norms governing race, class, and sex. As a result, his decision-making as governor can be, at times, confusing to modern researchers. The same man who mobilized the National Guard against white lynch mobs also upheld and defended what he perceived to be the righteousness of white supremacy and racial segregation. He decried women’s suffrage as a threat to that white supremacy but ultimately called upon the North Carolina General Assembly to ratify the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution. He led the charge for more and better mental health facilities but also publicly advocated for the institution of a state-funded eugenics program to sterilize those he viewed to be “incurable mental defective[s].”15

1. Bickett prevailed over Daughtridge with a final count of 63,121 to 37,017. John L. Cheney, editor, North Carolina Government, 1858-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History, (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State, 1981), 1375.

2. Frank A. Linney, “Partial Press and Democracy,” Union Republican (Winston-Salem), 20 April 1916.

3. “Keynote Speech of the Raleigh Convention is Made by Sen. Simmons,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 April 1916.

4. “To Democrats: Charlotte Man Talked to Guilford,” Everything (Greensboro), 29 April 1916.

5. Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, The Nomination of Thomas D. Warren to be United States Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, 66th Cong., 1st sess., 1919, 35.

6. “Bickett Thrills Great Crowd of Alamance Democrats at Graham,” News and Observer (Raleigh), 20 Aug 1916; “Cheering Throng was at Ashboro (sic) Saturday to Hear T. W. Bickett,” Greensboro Daily News, 27 Aug 1916;” Governor-Elect Bickett Addresses the Democratic Voters of Nash County,” Graphic (Nashville), 31 Aug 1916.

7. “Bickett Speaks to Large Audience,” News and Observers (Raleigh), 01 Oct 1916.

8. “Bickett Arouses Davidson Farmers,” News and Observers (Raleigh), 04 Oct 1916.

9. “A Voice from Craven County,” Union Republican (Winston-Salem), 26 Oct 1916.

10. Suffrage law in 1916 extended the vote to an incredibly narrow portion of the state’s citizenry, the result being that the electorate was largely comprised of white males over the age of 21. To maintain eligibility, of-age male citizens were required to be literate, to pay a poll tax, to have no criminal record, and to acknowledge the “being of Almighty God.” To ensure that no illiterate white men were turned away from the polls, the 1900 suffrage amendment also instituted a “grandfather clause.” The clause allowed illiterate white men to cast a ballot if they, or a lineal ancestor, had registered to vote before January 1, 1867. R. D. W. Connor, editor, North Carolina Manual, Issued by the North Carolina Historical Commission for the Use of Members of the General Assembly, Session 1917 (Raleigh, NC: Edwards and Broughton Printing Company, 1917), 340-342; James L. Hunt, “Grandfather Clause,” NCPedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/grandfather-clause, accessed January 23, 2019.

11. Final tallies for Bickett and Linney are officially recorded as 167,761 and 120,157, respectively. Cheney, North Carolina Government, 1858-1979, 1409.

12. “Linney and Bickett Exchange Messages,” News and Observer (Raleigh), 11 Nov 1916.

13. Connor, ed., North Carolina Manual, Session 1917, 256-261.

14. Connor, ed., North Carolina Manual, Session 1917, 261-262.

15. Thomas W. Bickett, “Message of Governor T. W. Bickett to the General Assembly of 1919,” 9 January 1919.