Exhibit Sections

Image

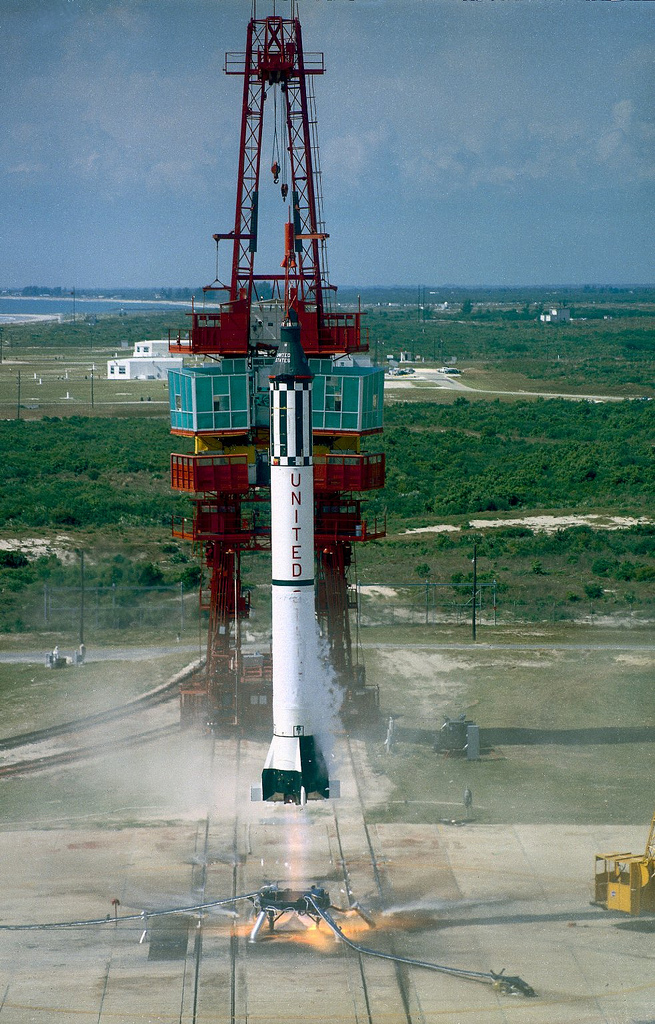

Project Mercury

America’s first man-in-space program ran from 1958 to 1963 and was known as Project Mercury.

Through Mercury, NASA sought to achieve three objectives: to successfully orbit a manned spacecraft, to study man's ability to function in space, and to return both man and spacecraft safely back to earth.

The Mercury program culminated in six successful “manned” missions. Some of Mercury's earliest testing, however, was completed by one unlikely astronaut with ties to the Tar Heel State.

Image

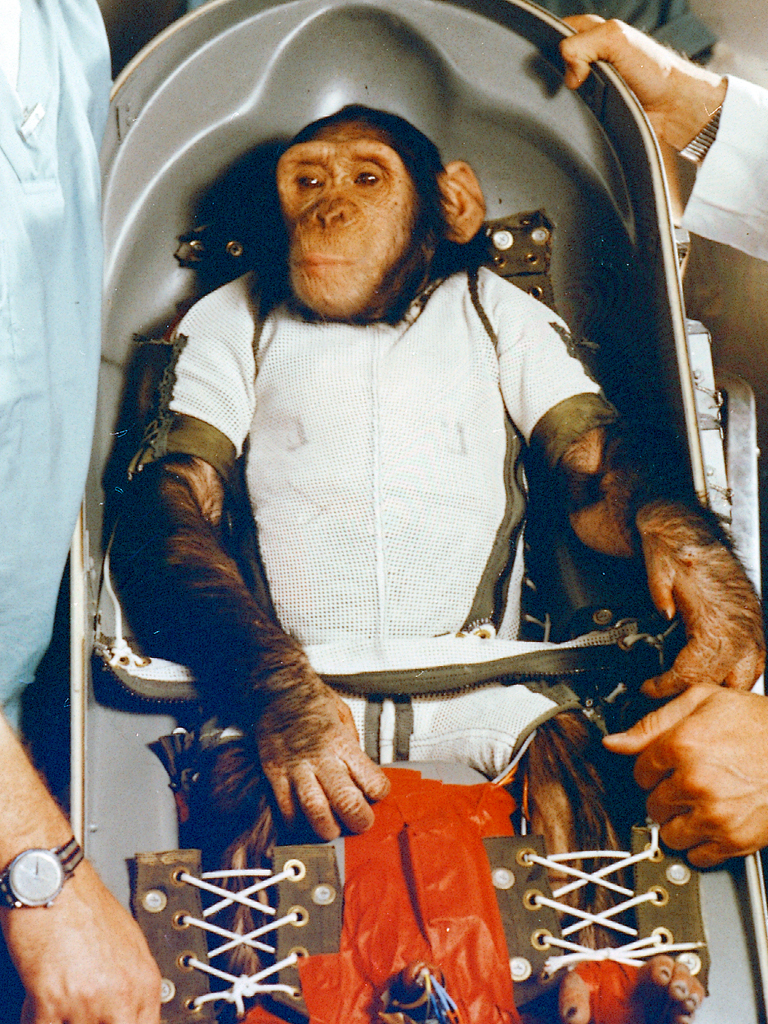

Ham, the Astrochimp

On January 31, 1961, an African-born chimpanzee named Ham successfully completed a 16-minute, 39-second suborbital flight. Traveling close to eight times the speed of sound (more than 6,000 miles per hour), Ham reached an altitude of 157 miles above the Earth’s surface.

In those sixteen minutes, Ham completed a series of simple tasks, manipulating levers, switches, and knobs in a certain order, proving that fine motor tasks could be completed at all stages of spaceflight, from launch to landing. His success demonstrated that manned space flight could be safely accomplished; three months later, Alan B. Shepard Jr. followed him into space.

In 1963, Ham was transferred to the National Zoo in Washington, DC, where he lived in relative isolation for seventeen years. Noting his loneliness, advocates arranged for Ham to relocate to the North Carolina Zoo in 1980 where he lived out the rest of his life surrounded by fellow chimpanzees. He died two years later, a national hero.

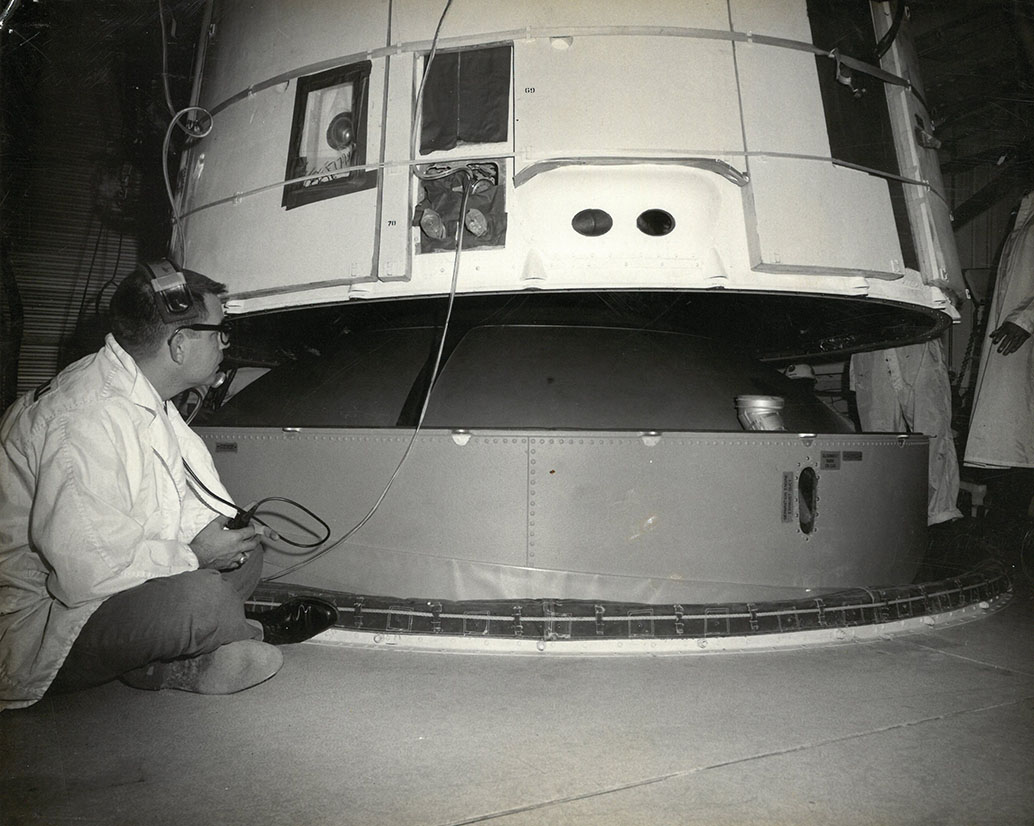

Image

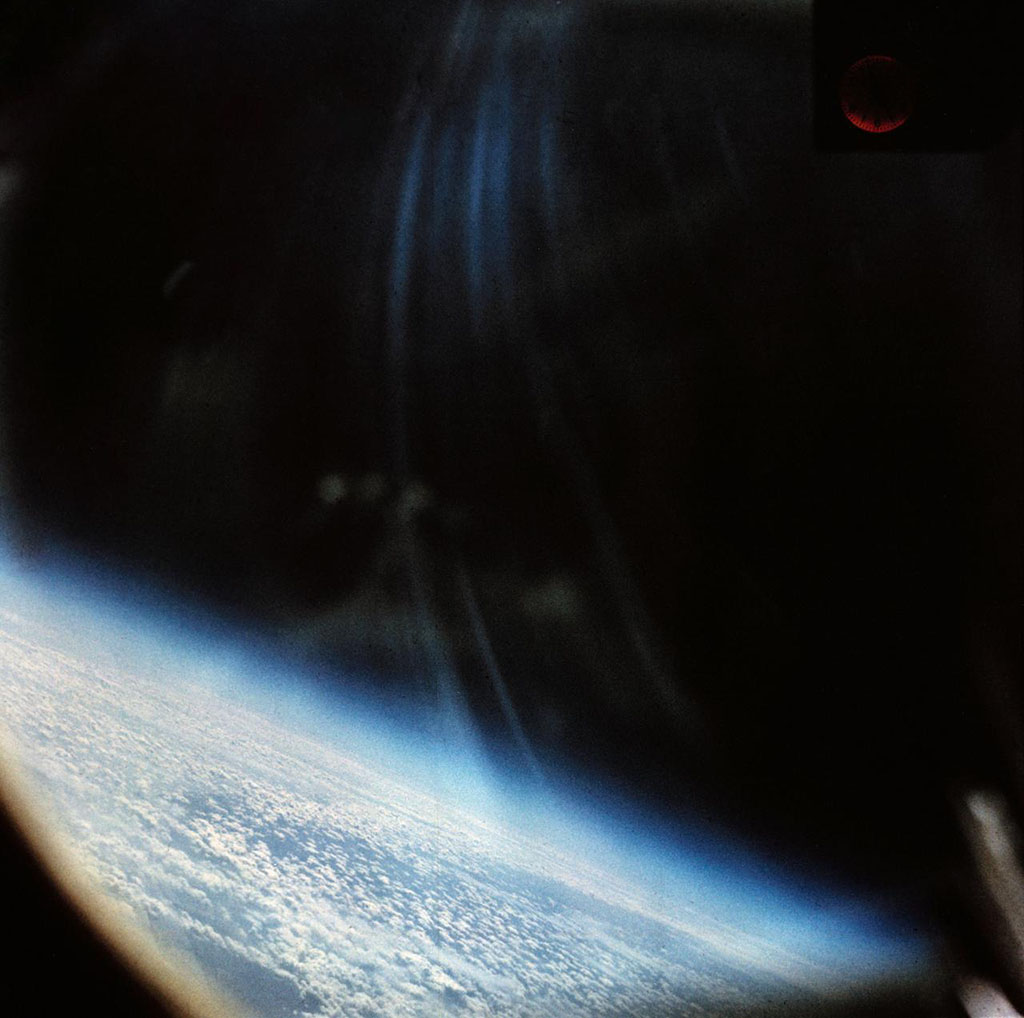

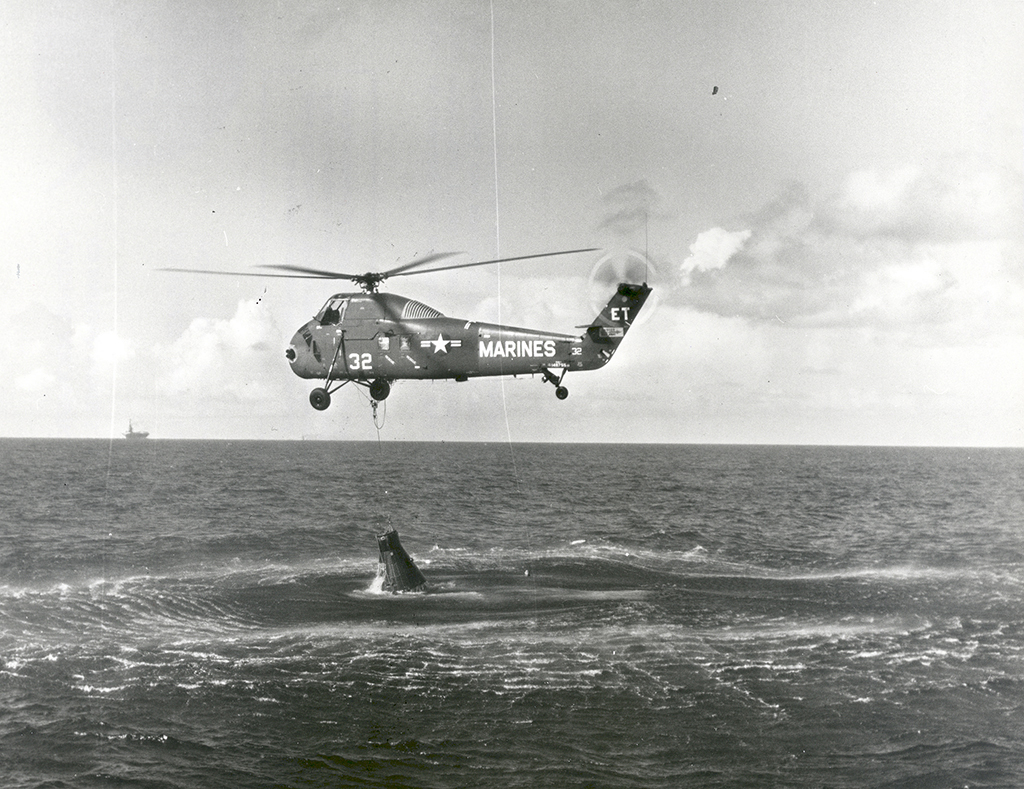

Early Capsule Recovery

Aviators from helicopter squadron HMR-262 stationed at the Marine Corps Air Station New River in Jacksonville, North Carolina, were crucial in developing early recovery procedures for Project Mercury. Pilot Wayne Koons, of Kansas, and co-pilot George Cox, a long-time resident of Newport, North Carolina, drew national attention for recovering astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. and his spacecraft Freedom 7, during Mercury-Redstone 3. Their experiences informed recovery planning up through the end of Project Apollo.

Exhibit Text

The historic film above shows the recovery operations of helicopter 44, of HMR-262, following the successful flight of astronaut Alan B. Shepard and Freedom 7. North Carolinian George Cox can be seen operating the winch during the recovery and welcoming Shepard aboard the deck of the USS Lake Champlain. Courtesy NASA.

You asked what was happening in the Space Program the day you were born. For the part I played in it, it was a very busy day.

—Samuel T. Beddingfield, to his daughter Beth,

March 27, 1980

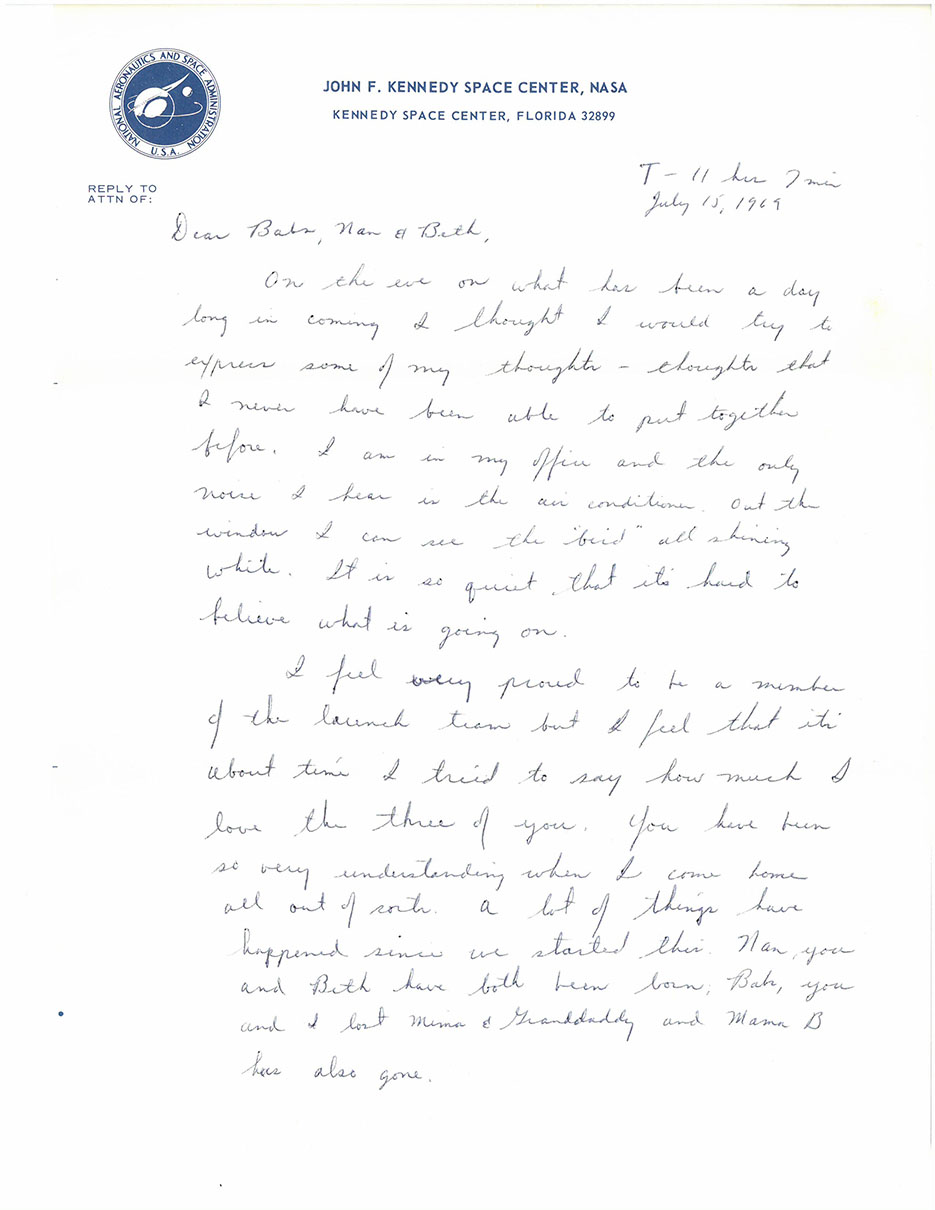

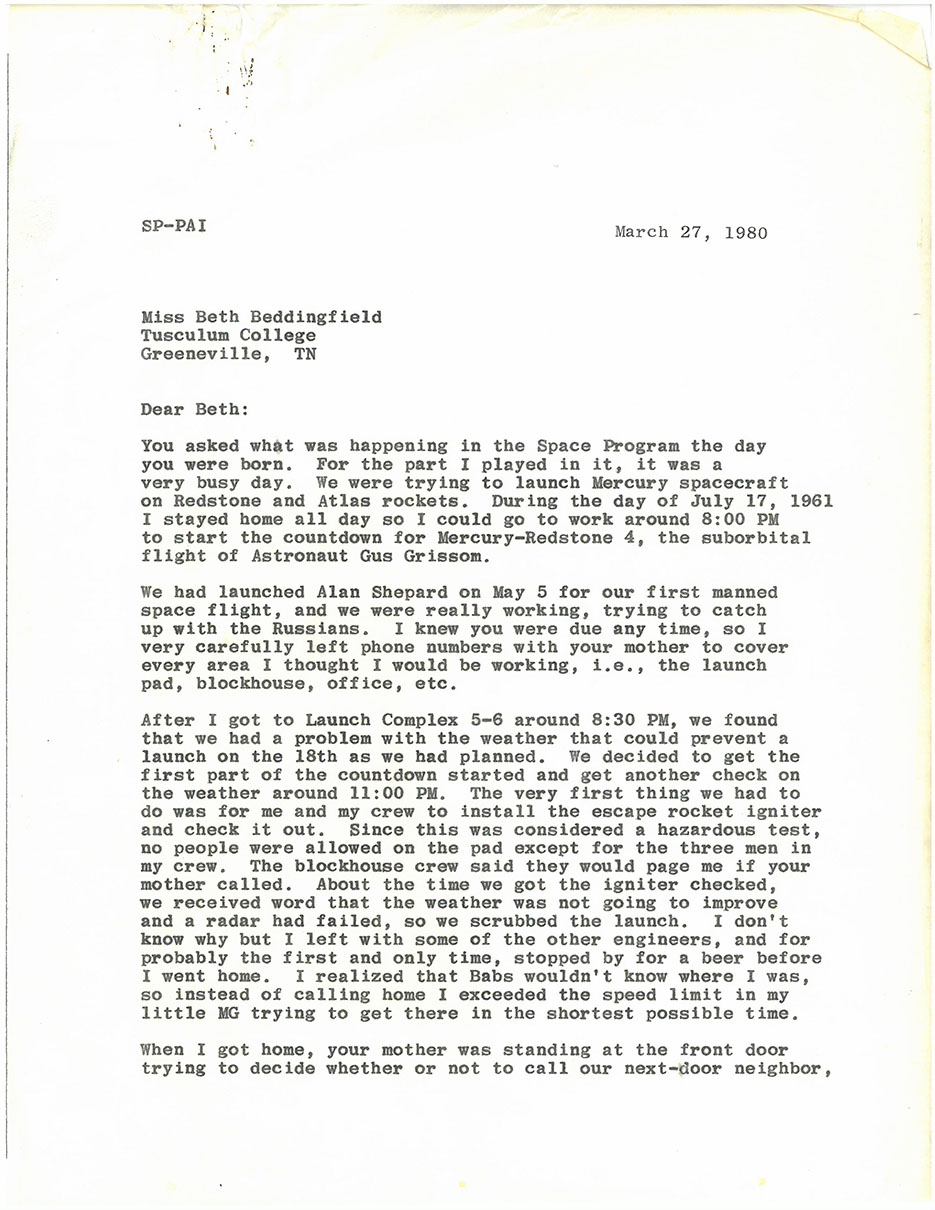

Image

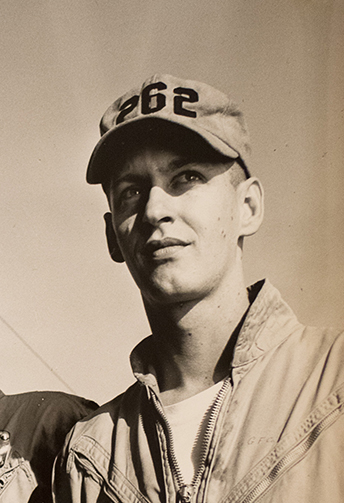

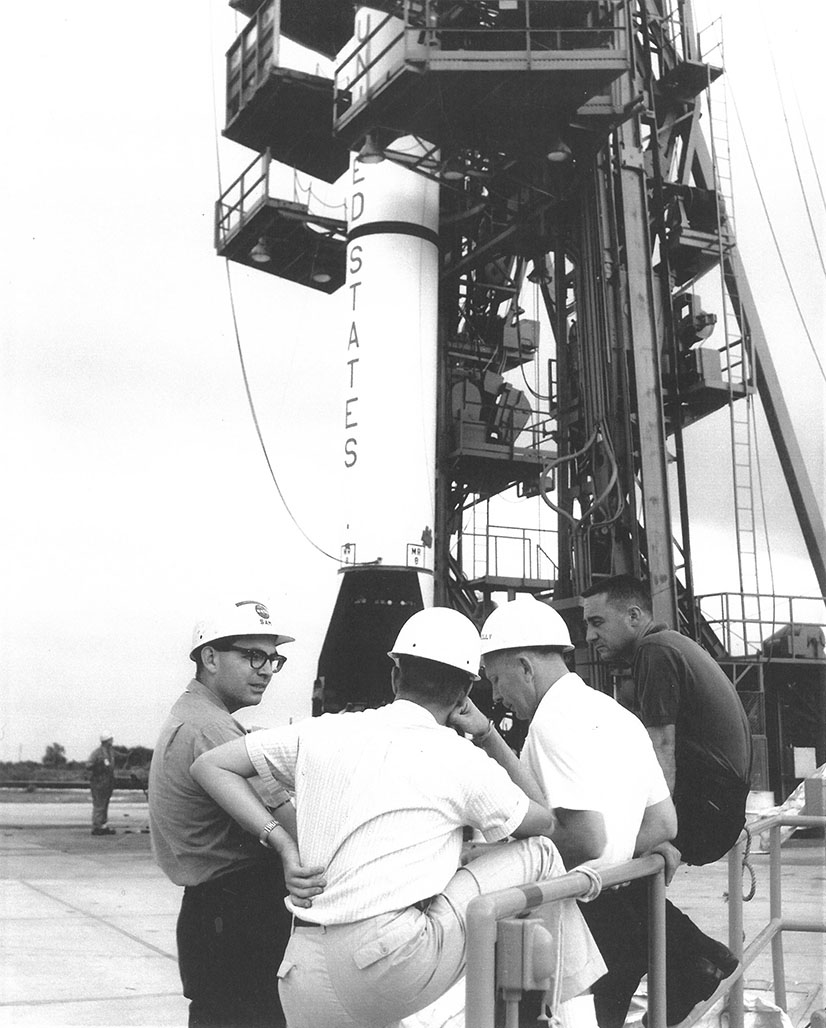

Engineering Mercury

Clayton native Samuel Beddingfield joined NASA as an engineer in 1959, becoming one of only thirty-three agency employees assigned to Cape Canaveral, Florida, at that time. During Mercury, Beddingfield oversaw mechanical and pyrotechnic operations, including the deployment and jettisoning systems for landing parachutes and capsule escape hatches. He concluded a twenty-six-year-career with NASA in 1985, when he retired from the agency as the deputy director of the space shuttle program at Kennedy Space Center.

Image

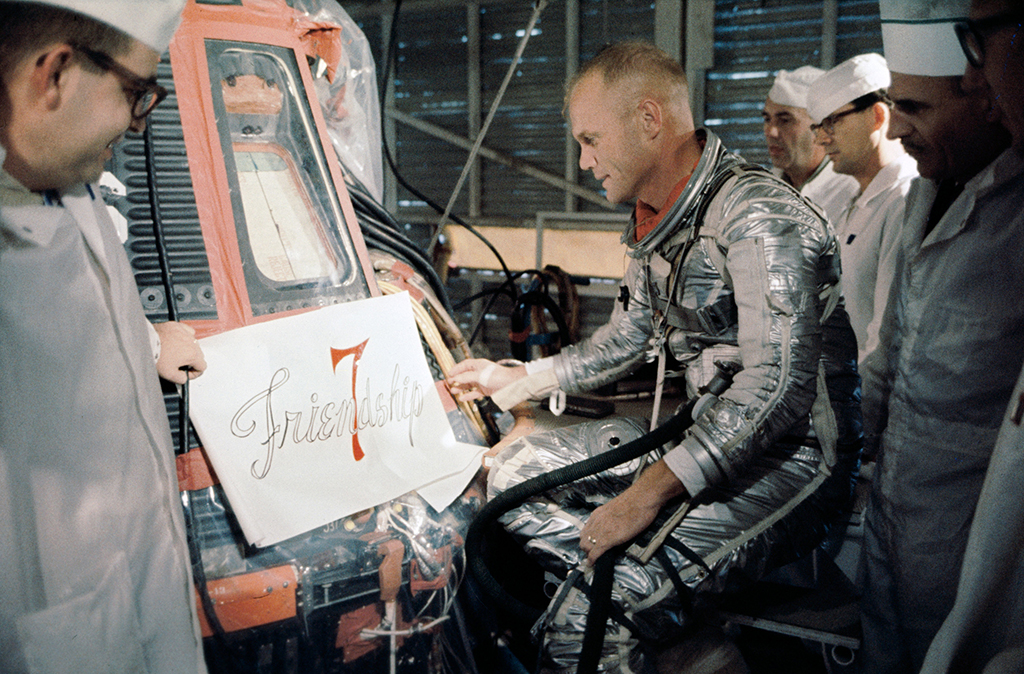

Celestial Navigation Training

One of the more crucial aspects of astronaut training occurred at Morehead Planetarium on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. From 1960 to 1975—through Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo—sixty-two astronauts attended the planetarium’s celestial navigation course, including eleven of the twelve men who walked on the Moon’s surface.

At Morehead, the astronauts learned how to navigate their spacecraft in the event that their flight instruments failed or otherwise became corrupted. The training guided astronauts home following emergency situations during Mercury-Atlas 9 and Apollos 12 and 13.

Image

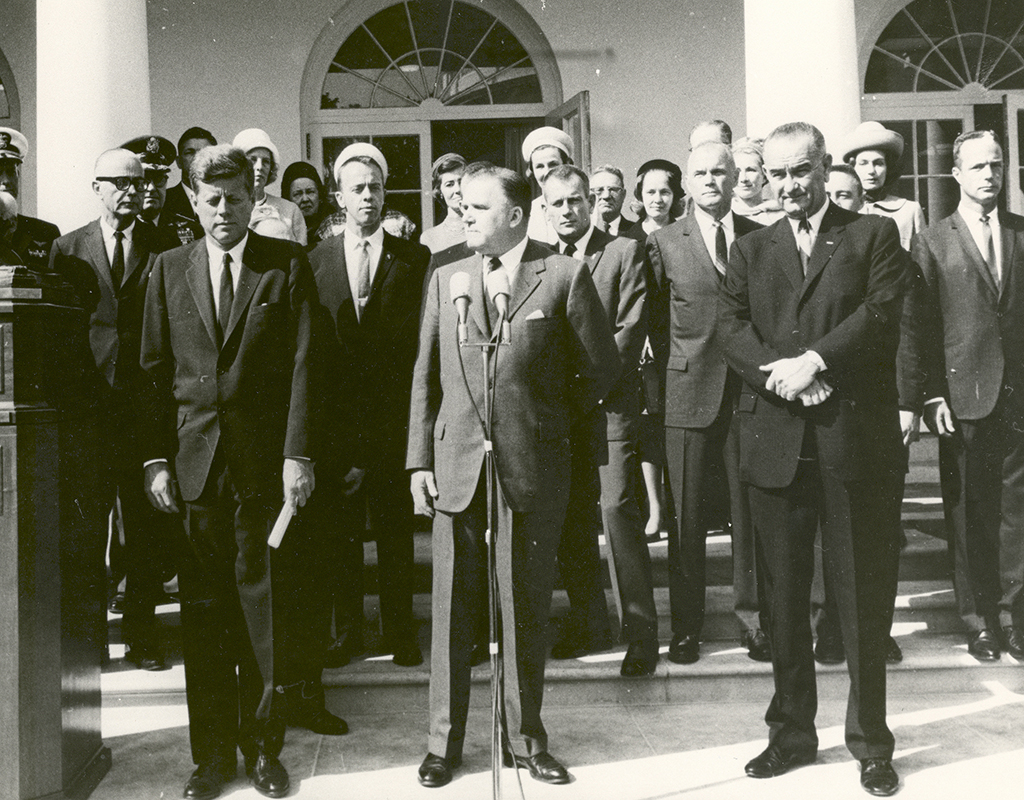

Administrator to the Stars

James E. Webb, a native of Tally Ho (Granville County) and graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was named NASA administrator by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. His charge: the goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Through Projects Mercury, Gemini, and the early years of Apollo, Webb’s leadership laid the groundwork necessary for American victory in the Space Race. In the words of later NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe, Webb turned “our imagination into reality. Indeed, he laid the foundations . . . for . . . astronomical discovery.”

Exhibit Text