Exhibit Sections

Image

Project Gemini

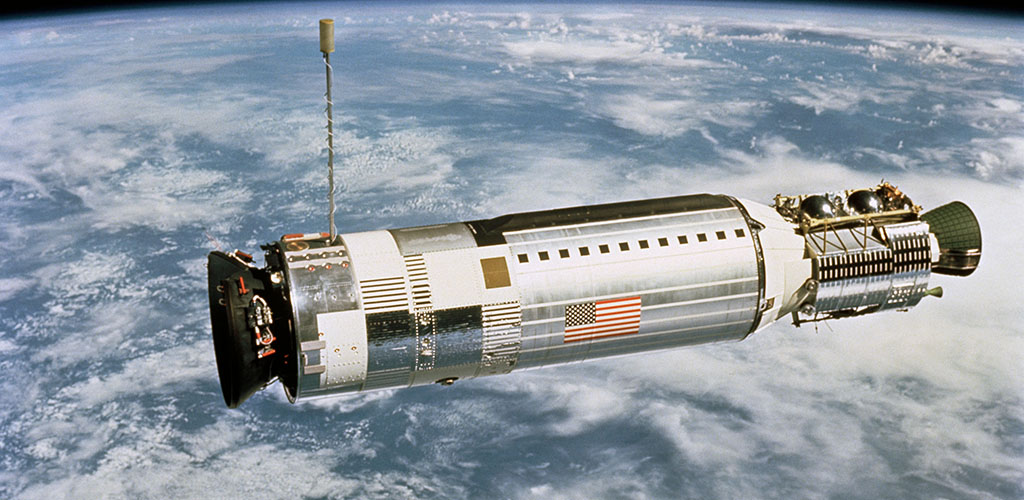

NASA’s second phase of space exploration was called Project Gemini. Gemini’s ten manned missions flew in 1965 and 1966, successfully demonstrating man’s ability to live and work in space for extended periods of time.

Primary aspects of the Gemini program included the implementation of spacecraft built for teams of two astronauts, the development of safer reentry and splashdown procedures, the introduction of maneuverability options to spacecraft, and the advent of “extravehicular activities,” or walking in space. Upon Gemini’s completion, astronauts and support staff were well prepared for the grueling six- to twelve-day missions of the Apollo program.

Image

Rogallo Wing

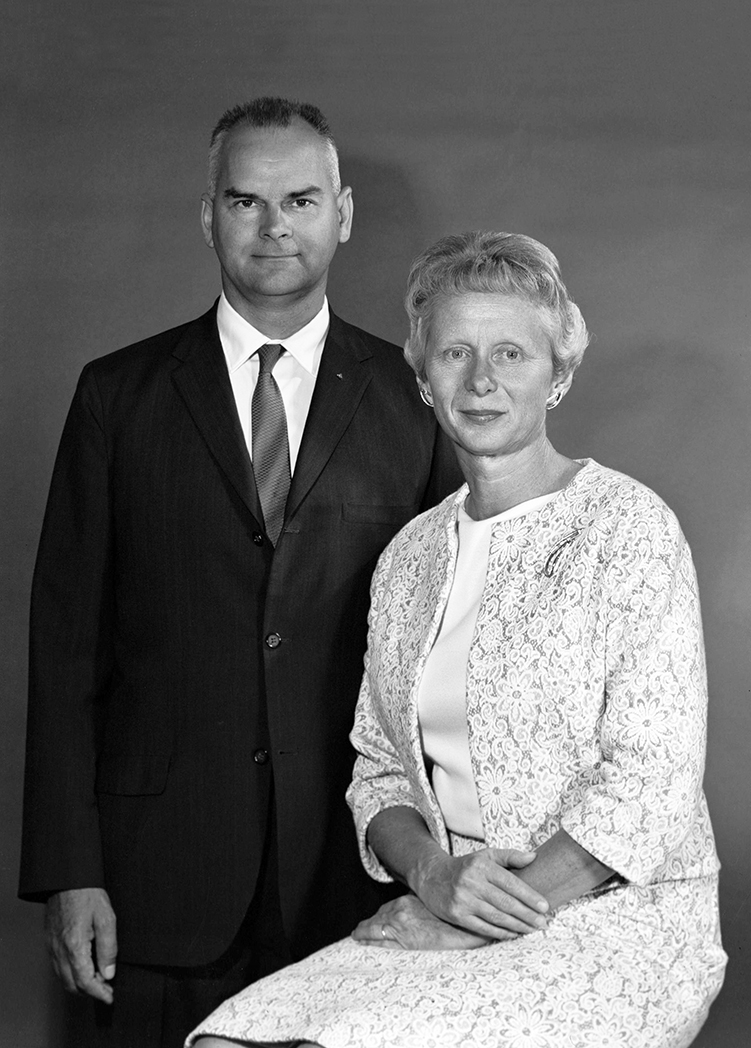

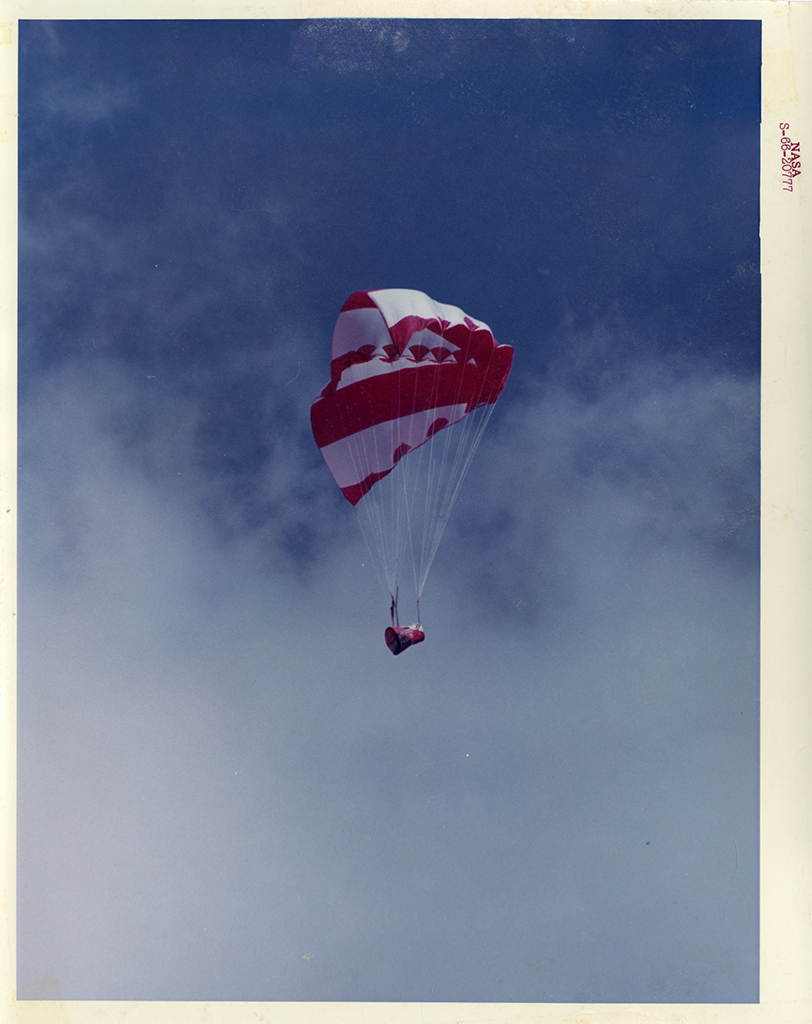

In the early stages of Gemini, NASA engineers developed an alternative to the parachute landing “splashdown” method that had been used with Mercury spacecraft. One of their options was a kite-like parawing, the creation of long-time Outer Banks residents Francis and Gertrude Rogallo.

The Rogallos’ parawing would have allowed astronauts to steer the Gemini capsule back to Earth’s surface and land it much like any other aircraft. Testing proved the concept, but engineers ultimately opted to retain the parachute landing system. While the Rogallos had missed an opportunity for space fame, their flexible-wing technology revolutionized the sport of hang gliding and remains in use to this day.

Image

Rosman Tracking Station

In 1963, NASA opened a Satellite Tracking and Data Acquisition facility on the edge of Pisgah National Forest near Rosman (Transylvania County). The chosen site exhibited several important qualities: it was government-owned, had an absence of light pollution, and was free of electromagnetic interference.

The base at Rosman, one of twenty-three located around the world, served as the primary east-coast tracking station for satellites and manned spacecraft. The base consisted of two dish-shaped antennas—one measuring an astonishing eighty-five feet wide—that sent and received commands, scientific data, and location information.

Image

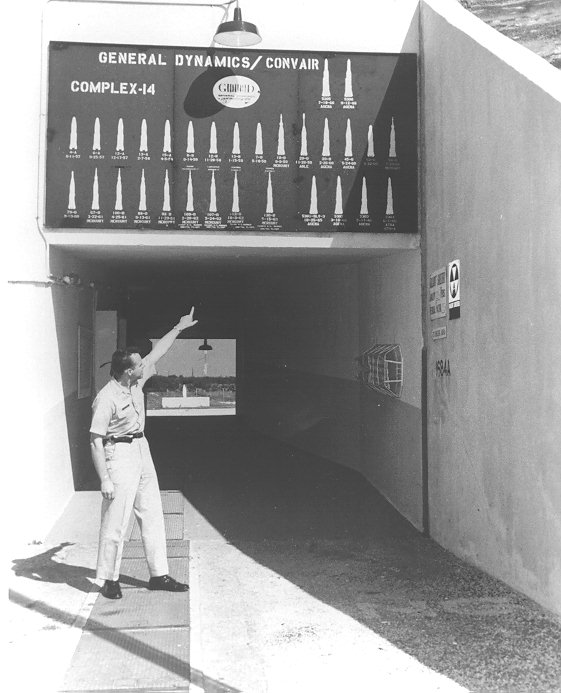

Agena Launch Director

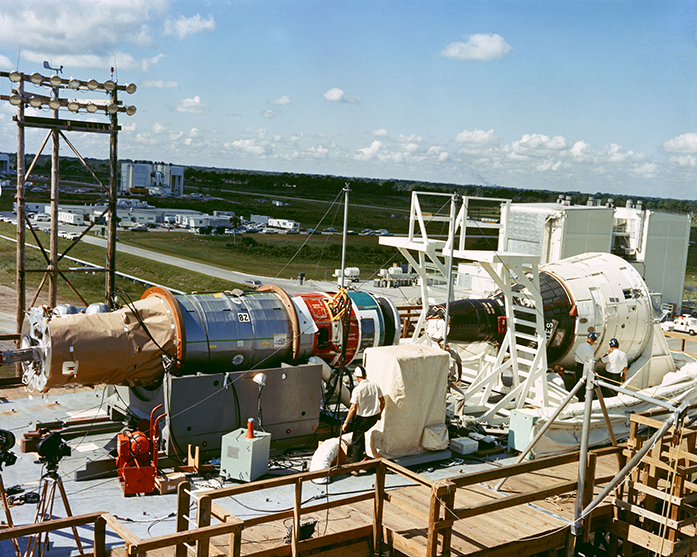

A key goal of the Gemini program was to successfully dock a crew capsule with another spacecraft while in orbit, a skill that would have to be tested and perfected before the space program could take on the Apollo missions. Gemini astronauts practiced the maneuver using an unmanned spacecraft called the Agena Target Vehicle. The two vehicles required separate, but perfectly timed, launches from Cape Canaveral. Any minor delay on the ground impacted the ability of the two crafts to rendezvous in space.

The high-stress environment didn’t deter Lt. Col. LeDewey “Jack” Allen of the Air Force’s 6555th Aerospace Test Wing. From 1963 to 1967, the Alamance County native served as commander of the SLV-3 Division, an assignment that also made him the launch director for seven Agena Target Vehicle launches in 1965 and 1966. Working in tandem with colleague and Gemini launch director Lt. Col. John G. Albert, Allen was responsible for running final checks on the Agena and its Atlas booster before giving the “go, no-go” status to NASA’s deputy director of launch operations.

Exhibit Text