History of Revolutionary War Pension Legislation

State Pension Act of 1784

The North Carolina General Assembly granted pensions to disabled Revolutionary War veterans. It also granted smaller pensions to widows and orphans of deceased veterans.

Federal Pension Act of 1806

This act provided federal pensions to all disabled veterans, including those who served in the state militia and Continental Line.

Federal Pension Act of 1818

This act allowed lifetime pensions to Revolutionary War veterans who had served at least nine months in the federal army or navy. To qualify, applicants had to demonstrate a financial need.

Federal Pension Act of 1832

This act granted at least partial pensions to all men who had served six months or more in any unit. Veterans no longer had to prove a disability or financial need to qualify.

Federal Pension Act of 1836

This act made Revolutionary War widows eligible to receive their husbands' pensions provided that they were married prior to the end of the war and never remarried.

Federal Pension Act of 1838

This act granted a pension to Revolutionary War widows who were married before January 1, 1794.

Federal Pension Act of 1848

This act allowed pensions to all qualifying widows who had married their husbands prior to January 2, 1800.

Federal Pension Act of 1878

This act allowed pensions to all widows of men who had served at least 14 days during the war, regardless of the date of their marriage.

What Does a Pension Application Consist of?

Pension applications required that a widow prove her marriage, her husband's military service, and her good moral character.

A federal pension application for a veteran required that the man make an affidavit proving his military service and obtain additional affidavits from locals supporting his claims and attesting that the man was well-respected in the community.1 Widows had to provide the same documents and also prove that she had married the veteran when she claimed. The bulk of an application was made of affidavits, which had to answer a number of questions set by the pension office and be sworn and certified before the local court, a time-consuming and confusing process for many elderly widows. These affidavits were even more difficult to obtain if the widow had moved recently (and so was lesser known in her community) or was too infirm to attend court in person.2

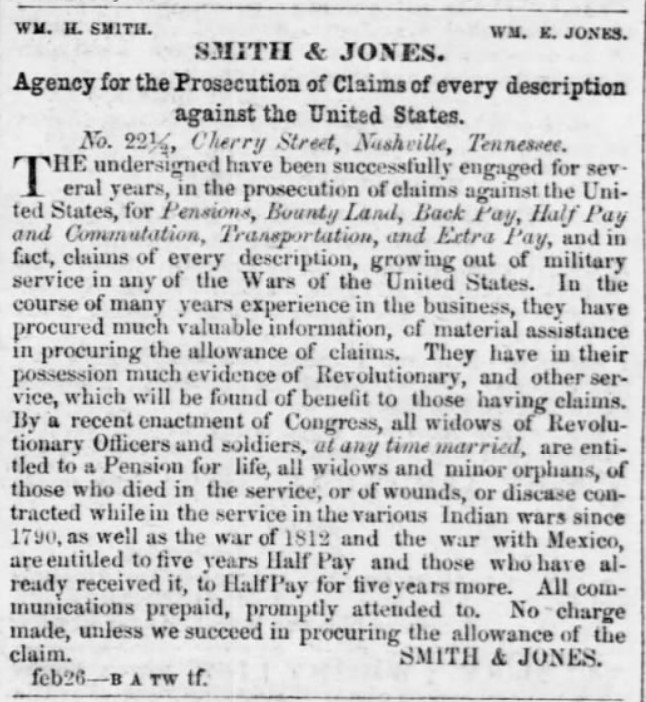

Compiling all these application materials was complicated, especially for elderly widows who were often illiterate, unfamiliar with the legal system, and who may have found it difficult to leave their homes due to their health. Consequently, most widows employed a pension agent or lawyer who would help assemble an application for them, typically with the understanding that the agent would receive a commission if the pension claim was approved. Agents became advocates for their clients, doggedly pursuing claims on widows' behalves when widows were unable to navigate the complex application system on their own.

Newspaper article from the Nashville Union and American, 15 March 1853. By offering pension services with no upfront cost, firms like Smith and Jones helped Revolutionary War widows pursue their claims.

What were the Outcomes of Pension Applications?

Although many widows' claims were approved, others were rejected due to a lack of evidence.

The pension office rejected applications for a variety of reasons. Commonly, it was because applicants did not provide enough detail in their statements or because their evidence contained contradictions. In 1832 Thomas Robison applied for a pension based on his service in the Caswell County Regiment of the North Carolina Militia. Though Robison thought he served in 1781, service records showed that a "Thomas Robertson" served in 1779. Because Robison's statement and the service certificate were "so much at variance," the pension office rejected it. Later in her own claim, Robison's widow Mary tried to explain the error. She stated that her husband's "memory was almost lost" in his later years and he had likely suffered from some form of dementia. She assured the office that the service records were correct, but because she had no other affidavits to support her claim, the pension office rejected her.

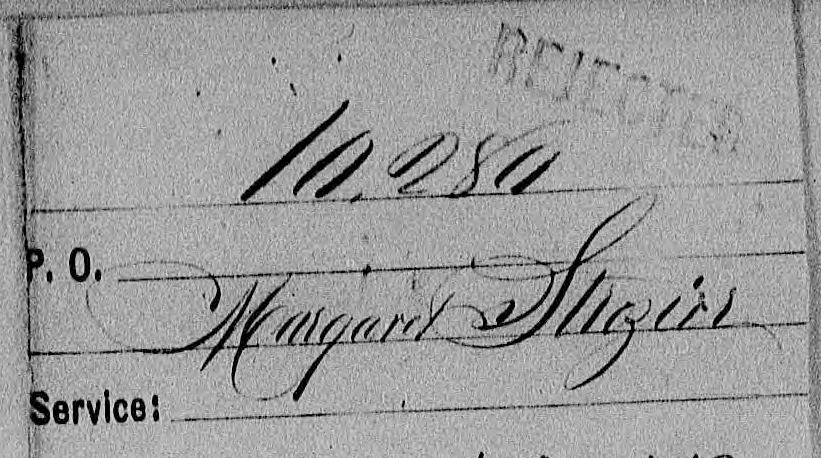

Even a small technicality might be enough to delay or reject an application. In 1836 Rosana Murray applied for a pension based on her husband John B. Murray's service. However, no "John B. Murray" appeared in the military service records, only "John Murray." Given it was a common name and Rosana did not know the exact units or dates of her husband's service, the application was rejected. Only after two more tries was her pension finally approved in 1850, fourteen years later.

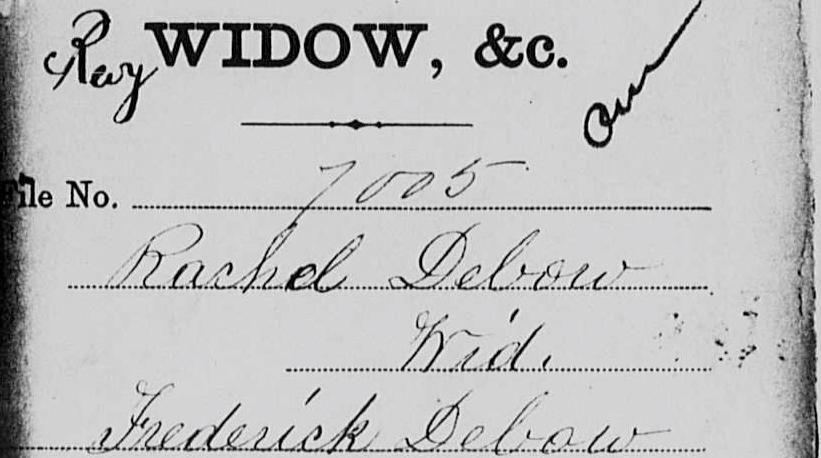

Rachel Debow's pension application. Her claim is noted as "am" or admitted. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Margaret Strozier's pension application. Her claim is stamped "Rejected." Courtesy of the National Archives.

Due to processing delays, some widows died before their claims were approved.

Some applications only took a couple months to process, but if the U.S. Pension Office determined that additional proof was needed, it might take years before a widow's pension was approved. And every widow did not always have years to wait. Lydia Ray first applied for a pension in 1837. In her application, she explained that her husband Joseph fell sick and died while on a furlough from the North Carolina Militia in 1780. Despite Lydia's claim that her husband died while he was in service, the pension office initially rejected her claim, arguing that his death was not classified as "in service," as he was on a furlough at the time. Moreover, Joseph had not served for at least three months in the militia, so Lydia did not qualify.

Lydia and her pension agent applied again in 1840, clarifying that Joseph had served a four-month tour in the North Carolina Light Dragoons in 1779. Therefore, Joseph had served enough time in the military prior to his death and Lydia was eligible for a pension even if they wanted to contest that her husband's death had not been while he was in service. The pension office delayed again, wanting additional proof of Joseph's dragoon service.

Finally in 1845 the pension office determined that they could approve Lydia's claim, but only if her agent proved the ninety-three-year-old was still alive. After the local county court clerk sent an affidavit proving Lydia was still living, the pension office approved her claim and issued a pension. Mail delays, however, meant that when the pension certificate arrived in December. It was too late, as Lydia had died just two weeks prior, unaware that she was ever recognized officially as a Revolutionary War widow.

What Can Pension Applications Reveal?

Pension records often contain the only extant record of a family's births and deaths.

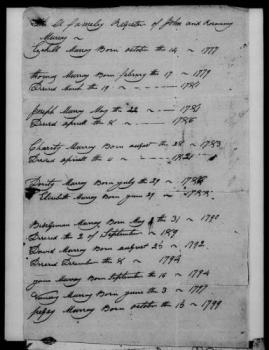

To be eligible under the 1836 federal pension law, Revolutionary War widows needed to prove that they had married a veteran before his term of service ended. One way to do this was by sending an official marriage certificate. Still, some women had long since lost this certificate, and not all county courts kept matrimonial records during that period. In the absence of a marriage certificate, the U.S. Pension Office also accepted a family's record of births (sometimes called a bible record because it was often written in the family bible) as evidence to prove a couple's marriage date. Instead of a certified copy however, the pension office increasingly only accepted the original record, often torn straight out of the bible, in an attempt to mitigate fraud.3

Once a pension application was processed, the birth record was not returned to the family, but instead remained with the claim, eventually ending up in the National Archives. Today, these birth records are a valuable resource for researchers and genealogists, but they came at a cost. Many applicants had intended to pass their bible records down through multiple family generations as a treasured heirloom. Instead, the listings of birth, marriage, and death data all end at the time the pension application was submitted, divorcing later generations from their early family history. The original family records available in pension claims today stand as a testament to the sacrifices families made to make sure Revolutionary War widows received the support they needed.

Family records like the one Rosana Murray submitted with her pension application can provide researchers with valuable geneological information.

Applicants hid facts that hurt their claims, like previous divorces.

Because pension applicants wanted their claim to succeed, they may have hidden details about their life that made them ineligible, like a divorce. For example, Ruth Edwards, a Revolutionary War widow residing in Yancey County, may have obscured details about her divorce in her pension application.

Pension forms often never asked applicants directly if they had been divorced, as the practice was relatively uncommon. Prior to 1790, there were no formal laws or processes regarding divorce in the State of North Carolina. When a law passed in 1790, it required either spouse to file a petition directly with the North Carolina General Assembly, a daunting task few couples followed through with. Even then, the state granted its first legal divorce in 1794.4

Although Ruth and her husband John filed for a divorce with the Buncombe County court, they did not submit anything to the state legislature, meaning if they did separate, it was not technically legal. Whether their separation was legally official or not, by 1800 Ruth and John were listed separately on the Burke County census. Later, family tradition suggests that John went to live with his sister in Washington County, Tennessee, while Ruth only appeared on censuses in North Carolina.5 We can't know the true nature of the Edwards' marital arrangement, but their case does demonstrate how pension records can sometimes raise more questions than answers.

Many widows used the pension process to share many details about the entirety of their lives.

When some widows came before their local county courts to apply for a pension, they had a lifetime of experiences to share and a captive audience. Revolutionary war widows, many of whom were illiterate or otherwise left no personal papers themselves, used the pension application process as an early form of oral history.

Pension applications are illuminating not only for the descriptions of Revolutionary soldiers and their service histories, but the extra details that women added to their retelling. Rachel Debow, for example, talked about how she sowed oats in the field while her husband was away. Lydia Ray's pension application contained information about her career as a midwife after her husband died during the war, as well as an exasperated note from her lawyer to the pension office asking that the pension office approve her claim soon so that she would stop bothering him about her claim. While her lawyer may have found Lydia's pursuit of recognition irksome, the note now stands as a testament to how doggedly Lydia and countless other widows like her asserted themselves and demanded recognition for their wartime experiences.

Even though it was not relevant to her wartime experiences, Lydia Ray's application includes information about the thirty years she spent as a rural midwife.

Special thanks to Riley Sutherland and Connie Schulz for their assistance with the inception of this topic.

- National Archives and Records Adminstration, Descriptive Pamphlet for Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, M804 (Washington, DC: NARA, 1974) 1-3; The National Archives' Prologue Magazine has published a variety of helpful articles highlighting the history of and various uses for the revolutionary pension claims in their collection. See Jean Nudd, "Using Revolutionary War Pension Files to Find Family Information," Prologue Magazine (Summer 2015) 47:2 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2015/summer/rev-war-pensions.html (accessed 4 January 2023); Damani Davis, "The Rejection of Elizabeth Mason: The Case of a 'Free Colored' Revolutionary Widow," Prologue Magazine (Summer 2011) 43:2 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2011/summer/mason.html (accessed 4 January 2024); Claire Pretchel-Kluskens, "Follow the Money: Tracking Revolutionary War Army Pension Payments," Prologue Magazine (Winter 2008) 40:4 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2008/winter/follow-money.html (accessed 4 January 2024); Theodore J. Crackel, "Revolutionary War Pension Records and Patterns of American Mobility, 1780-1830," Prologue Magazine (Fall 1984) 16:3 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1984/fall/pension-mobility.html (accessed 4 January 2024); Constance B. Schulz, "Revolutionary War Pension Applications: A Neglected Source for Social and Family History," Prologue Magazine 15 (Summer 1983): 103-114.

- Other works that discuss the early history of pension legislation include: Michael A. McDonnell and Briony Neilson, "Reclaiming a Revolutionary Past," Journal of the Early Republic 39:3 (Fall 2019), 467-502; John P. Resch, "Politics and Public Culture: The Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818," Journal of the Early Republic 8:2 (Summer 1988), 139-158.

- Applicants and their families were sometimes hesitant to send in the originals of their family record, even if it meant a delay in their claim. In 1839 Huldah Hill's son William wrote to the U.S. Pension Commissioner stating that the government should accept the certified copy of the record he had sent instead. He wrote of the register, "it belongs to the family alone. I Shall keep my farthers register and hand it down in my family as he has done." Letter from William Hill Jr. to James L. Edwards. In 1840 when the pension office refused Huldah's pension due to the lack of an original register, William wrote again that "I think no respectable family will [send their original register], that I take it as an insult from your department to my family." Letter from William Hill Jr. to James L. Edwards, 9 October 1840. It was only in 1845 when they finally sent the original family record, and five years after Huldah Hill had died, that the pension office approved the Hill's claim. Affidavit of Jonathan J. Hill and William Hill in support of a Pension Claim for Huldah Hill, 24 April 1845.

- Cynthia Kierner, The Tory's Wife: A Woman and Her Family in Revolutionary America (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2023) 128-131. In 1814 the state passed another law, moving the issue of divorce proceedings to the courts, rather than to the legislature.

- 1800 Census, Morgan, Buncombe County, North Carolina, National Archives M32, Roll 29, Page 167-168; 1830 Census, Buncombe County, North Carolina, National Archives M19, Roll 118, Page 284; Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society, "Edwards Family," OBCGS.com, https://www.obcgs.com/edwards-family/ (accessed 9 January 2024); Rob Neufeld, "Visiting Our Past: With the Constables in 1790s Buncombe County," Citizen-Times (Asheville, NC), 13 November 2016, https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2016/11/13/visiting-our-past-constables-1790s-buncombe-county/93671380/ (accessed 9 January 2024).

.jpg)