North Carolina's colonial court system was a complicated one. With multiple types of courts, all with specific purposes, it can be difficult for researchers today to understand how the system worked. A wide variety of cases ranging from livestock theft, to land sales, to murder might come before the same group of judges but titled as separate courts. Because of the eclectic nature of these cases, colonial court records are a valuable source for historians today, but only if one understands where to look.

The historic Chowan County Courthouse, built in 1767, is the third courthouse of its kind to stand on the property. The first courthouse, built in 1719, was also the seat of the colonial assembly. Courtesy of Historic Edenton.

From Carolina’s establishment as a colony in 1663 until 1729, the colony’s most important governing body was the North Carolina Council.

Like the state and federal government today, North Carolina’s colonial government was made of three separate branches: the executive branch, the legislative branch, and the judicial branch. The head of the executive branch was the colonial governor, and he had a board of advisors, typically six to twelve leading men in the colony, called the North Carolina Council.

The council advised the governor, served as the main executive body in the governor’s absence, and during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, council members also served as officers of the General Court. Early council members acted as general court judges interchangeably, often issuing judgements for major crimes and disputes as part of their regular council proceedings.

Later when the General Court became more formalized, many current or former members of the North Carolina Council sat on the court as judges or members of the jury, further muddling what was an official action of either the court or the council.

Due to this loose distinction between the council and the court, historians today group council proceedings together with court records to better understand how officeholders shaped and enforced laws within colonial society.

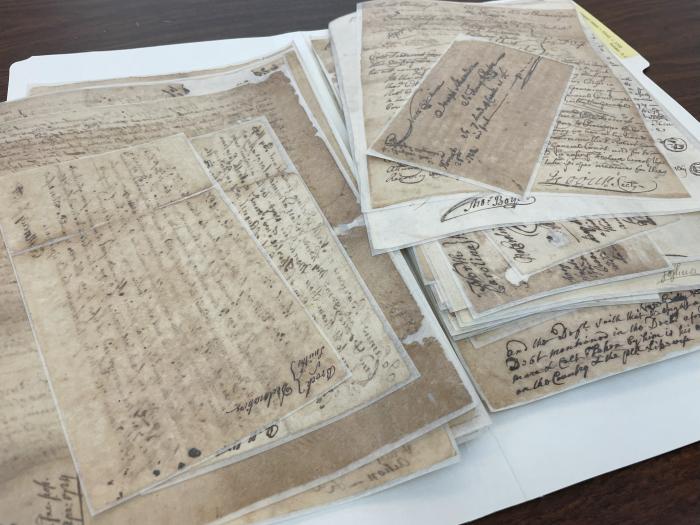

Today, North Carolina colonial court records are bound and conserved in the permanent collection at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh. Courtesy of SANC.

As the colony expanded through the 1700s, the bureaucratic structure of the colony's court system also grew.

Aside from the General Court, members of the council also sat on a separate court, called the Court of Chancery, which granted things other than criminal punishments or monetary damages, such as writs or injunctions. The General Court, the Court of Chancery, and the Admiralty Court (concerned with maritime law and seafaring) made up North Carolina’s higher court system.

At the lower court level, counties (called precincts before 1739) also had their own local courts. Leading men from each county served as justices and heard both civil and criminal cases. In more serious cases or ones that needed appeal, the matter then transferred up to the higher courts.

Compared to what we think of the justice system today, these colonial courts were rather informal. Rather than being held in a courthouse, many early courts convened in prominent community member's private residences. Moreover, they only met for a couple days at a time, three or four times a year, meaning that trial proceedings could easily take several seasons or years to settle.1

In the 1750s, as the colony's legal caseload grew even larger, North Carolina established a series of district superior courts which acted as the new higher court system. Regionally based in places like Edenton, Wilmington, Salisbury, and New Bern, the superior courts, like their county court counterparts, kept separate records for their criminal and civil proceedings.2

Portrait of Christopher Gale by Henrietta Johnston. Gale (c.1679-1735) was the first Chief Justice of North Carolina appointed independently of the governor. His tenure saw the colony's legal system rapidly expand and professionalize. Courtesy of North Carolina Museum of History.

The complicated nature of North Carolina’s colonial court system means that records relating to American Indians are often difficult to find.

When navigating the North Carolina colonial court collection today, researchers will find that records are separated out by court type (general court, chancery court, district court, etc.), year, and case type (civil action or criminal action).

Despite this organization, only a fraction of the collection has been described in finding aids, let alone transcribed. Between finding the correct box and sorting through the hundreds of handwritten documents in each, searches for specific documents or topics can easily take hours. It also means there is plenty for historians today to still discover!

Finding American Indian documents specifically within this collection poses additional challenges. American Indians and their experiences appear at every level of the court records. Additionally, when advocating on behalf of their nations, American Indians also appeared before the Colonial Council rather than the General Court, as they were there for a diplomatic rather than legal purpose. Finally, not all interactions with American Indians were recorded and preserved, meaning that what remains in the archives today often provides more questions than answers.

Today, North Carolina colonial court records are organized by court type and year but are not transcribed, meaning it can take time to find specific documents on special topics such as American Indians. Courtesy of SANC.

The American Indian records in this edition are not meant to be an exhaustive collection of every instance an American Indian interacted with the colonial court system. Instead, MosaicNC editors hope that the documents contained in this collection provide useful examples of the variety of ways American Indians of many backgrounds interacted with colonial society.

For this exhibit, as well as all other content on MosaicNC, editors use the term "American Indian" rather than other terms such as "Native American," "Indian," or "Indigenous." The North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs and the North Carolina American Indian Heritage Commission both also prefer the term "American Indian." Whenever possible, however, the editors strive to refer to culturally distinct groups of native people by their appropriate tribal names.

For more information on MosaicNC's editorial policies for American Indian terminology, see our Editorial Statement on American Indian Terminology.

- North Carolina Higher-Court Minutes 1709-1723, ed. William S. Price, Vol. 5 (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, 1974) xxvi-xxxvii.

- "Finding Aid for the Colonial Court Records Group, 1665-1787, SR.401," State Archives of North Carolina https://appx.archives.ncdcr.gov/findingaids/SR_401_Colonial_Court_Records_G_.html (accessed 15 October 2024).