Oftentimes, the American Indians that appeared before the North Carolina Colonial Council or General Court did so not only for themselves but on behalf of their larger nation. American Indian nations such as the Yeopim and the Chowanoke appealed to the council directly with their concerns, as one sovereign government to another. Even when dealing with individual American Indians, the North Carolina government had to consider the diplomatic ramifications any decision might have on the colony’s relationship with American Indian tribes.

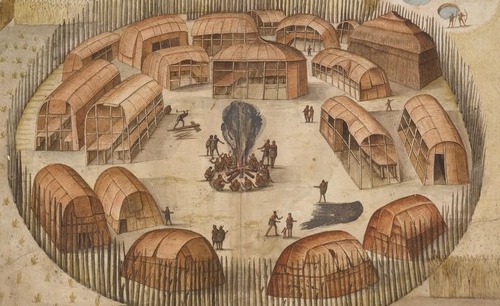

For centuries American Indians in North Carolina lived communally in villages like Pomeiooc, a Secotan village illustrated by John White in about 1585. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

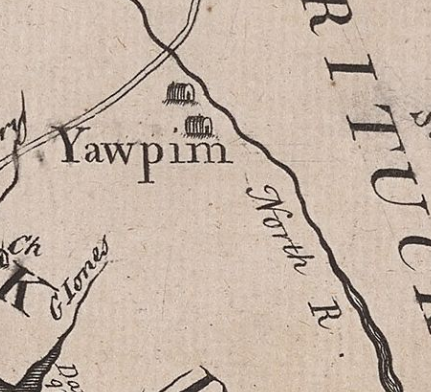

American Indian Nations like the Yeopim appealed directly to the North Carolina Council whenever any disputes with colonists arose.

When British colonists encroached on their native land, American Indian tribes like the Yeopim of the northeastern shore of the Albemarle Sound petitioned the colonial government. Although they could have taken the trespassing colonists to court on an individual basis, the Yeopim brought to their issues to the council directly, considering the encroachment a direct threat to their sovereignty as a nation independent of the British.

As historian Michelle Lemaster argues, by directly petitioning the British colonial government, tribes like the Yeopim “considered their appeals to the colonial government as a form of diplomacy… tribes were not exhibiting submission to English law but rather the independent action of a people interested in preserving their status under the terms of their treaty agreements with other people."1

The Yeopim's 1697 appeal was successful. The North Carolina Council ordered that no colonist be allowed to occupy land within three miles of the Yeopim’s settlement. They later formalized the Yeopim’s territorial boundary in 1704 through a survey.

However, as was the case for many other American Indian nations, the growing numbers of European colonists threated the Yeopim’s independence. As the Yeopim's population waned, more colonists began to encroach on native land, and the Yeopim found themselves without the diplomatic weight to stop it. By 1739, unable to halt the encroachment, the Yeopim sold parts of their land to colonists.When the colony stopped formally recognizing the Yeopim as a coehsive tribal troup, those tribal members who remained had not choice but to integrate themselves with the rapidly expanding colonial society.

The Yeopim Indian village in Pasquotank Precinct, illustrated on a 1733 map of North Carolina by Edward Moseley. Courtesy of East Carolina University Digital Collections.

American Indians like the Chowanoke dealt with land ownership as a collective, coming together to sell land as a cohesive group.

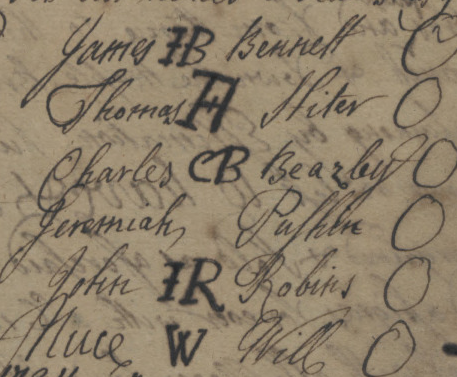

As American Indian tribes like the Chowanoke slowly began to cede portions of their land to colonists in the 1730s, it was not a step they took lightly. Chowanoke leaders like James Bennett and Thomas Hoyter worked collectively, with several Chowanoke leading men signing each land grant.

In Chowanoke culture, like that of many other American Indian groups, there was no concept of individual land holdings. Because everyone lived on and used the land together, agreements about selling the land and using the proceeds of those sales had to be done collectively.

Rather than the individual colonists brokering land purchases with the Chowanoke directly, colonists had to receive approval from the North Carolina Council as well to make sure colonists were not seizing “Native lands without proper payment and title.”2 In other words, the North Carolina Council took part in these land sales because colonists were making land deals not with fellow British citizens, but with a sovereign nation.

These land sales had the potential to not only affect individual colonists and their Chowanoke peers, but the colony’s diplomatic relationships with American Indians in the region on the whole.

Six Chowanoke leaders signed a 1734 deed granting James Hinton about 500 acres of land from their historic homelands. Although the leaders could not sign their own names, they signed via mark, or initialed the document. The names read: "James JB Bennett, Thomas TH Hiter, Charles CB Beazley, Jeremiah Pushin, John JR Robins, and Nuce W Will." Courtesy of North Carolina State Archives.

Disputes between individual colonists and Indians could become diplomatic incidents, like in the case of Christopher Dudley's assault on Sighacka Blount.

In 1723, a small dispute about hunting rights had North Carolina colonial officials fearing the start of a second Tuscarora War when colonist Christopher Dudley assaulted an elderly Tuscarora man named Sighacka Blount.

That March, Blount and several other Tuscarora hunters visited colonist Richard Nixson’s house on their way to catch beavers in Beaufort Precinct. Nixson’s neighbor Christopher Dudley confronted Blount and the other Tuscarora, telling them the land was his and they had no right to hunt there, as they’d scare his livestock. When Blount made no response, Dudley became enraged and attacked him, breaking Blount’s arm.

Sighacka Blount did not fight Dudley back. However, by relying on his sovereign status as a member of the Tuscarora Nation, Blount calmly found a way to ensure that the colonist was punished for the assault. After Richard Nixson and other colonists pulled Christopher Dudley away, Sighacka, rather than going to the local colonial magistrate or justice of the peace, said he would go tell Tom Blount, the Tuscarora tribe's leader in North Carolina, about the incident. Tom Blount, in turn, would tell Colonel Robert West, a colonist who worked as a special liason between several American Indian nations and the NC Colonial Council.

The implications of Sighacka Blount's decision to get Tuscarora leadership and Col. West involved in the dispute were clear to the North Carolina Colonial Court. By assaulting Blount, Dudley risked igniting a much larger war between the colonists and the Tuscarora people if the issue was not resolved quickly and to the American Indians' satisfaction.

With the bloody events of the Tuscarora War that had ended just seven years prior weighing on their minds, the North Carolina General Court indicted Dudley for assault.3 Chief Justice Christopher Gale personally signed Dudley's arrest warrant, noting how Dudley's assault could cause "many ill conveniences... to the Tranquility & p[e]ace of this Government."

Any records about the outcome of the case have not survived. Still, it is clear American Indians like Sighacka Blount leveraged their identities as members of a sovereign nation to make the colonial government consider their claims as part of larger tribal-colonial diplomatic relations.

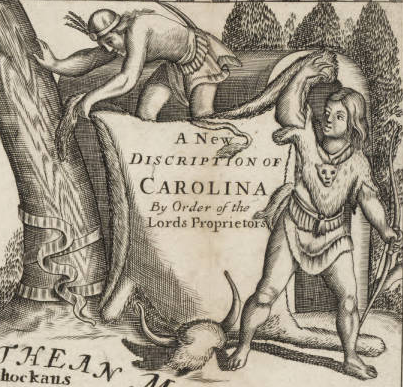

A hunter, Sighacka Blount might have looked similar to the American Indian hunters illustrated on John Ogilby's 1671 map of Carolina. Courtesy of University of North Carolina.

For this exhibit, as well as all other content on MosaicNC, editors use the term "American Indian" rather than other terms such as "Native American," "Indian," or "Indigenous." The North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs and the North Carolina American Indian Heritage Commission both also prefer the term "American Indian." Whenever possible, however, the editors strive to refer to culturally distinct groups of native people by their appropriate tribal names.

For more information on MosaicNC's editorial policies for American Indian terminology, see our Editorial Statement on American Indian Terminology.

- Michelle LeMaster, "'In the Scolding Houses': Indians and the Law in Eastern North Carolina, 1684-1760," North Carolina Historical Review, 83:2 (April 2006) 196.

- Warren E. Milteer Jr., "From Indians to Colored People: The Problem of Racial Categories and the Persistence of Chowans in North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review, 93:1 (January 2016) 35.

- David La Vere, "Making War on the Deer: Deer Hunting and Deerskins in Colonial North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review, 101:1 (January 2024) 35-36. For more information about the Tuscarora War, see La Vere, The Tuscarora War: Indians, Settlers, and the Fight for the Carolina Colonies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013).