American Indians occasionally appeared before the colonial court system individually. By the mid 1700s, American Indians increasingly utilized the colonial court system for settling interpersonal conflict. Historians have interpreted this dependence as an indicator of the waning power of many North Carolina Indians’ tribal authority.

Whatever the nature of American Indians’ use of the colonial court system, their legal interactions reveal interesting insights about American Indians’ changing culture and society.

Inset of an American Indian man from the 1770 John Collet map of North Carolina. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

American Indians like Sanders appealed directly to the colonial court because they lacked a tribal community.

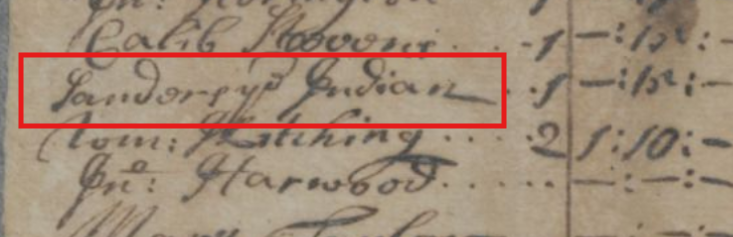

Sanders was an American Indian man that arrived in North Carolina by 1685 as an indentured servant. Originally indentured to New England merchant Joshua Lamb, Sanders might have been a prisoner of war from one of the several American Indian nations that fought the colonists during King Philip’s War such as the Wampanoag, Narragansett, or Wabanaki. Though Sanders' knew his own identity, by the time he arrived in North Carolina, his colonial contemporaries did not view his tribal nation as important enough to record. Instead, they opted to strip him of his cultural identity and referred to him simply as "Sanders the Indian." Whatever Sanders’ tribal identity was, he’d have been entirely cut off from his native community and culture.

Sanders first appeared before the North Carolina colonial court in 1705 when he appealed for the government’s help in ending his servitude after being forced to sign an exploitative contract. After arriving in North Carolina, Sanders’ service was sold to Joseph Scott. In 1692 following the deaths of Scott and his wife, Sanders' indentured passed to the couple’s adult daughter, Juliana Laker. Laker then forced Sanders to sign a contract extending his servitude twelve more years. Despite the terms Sanders remained Laker's indentured servant up through 1705, a full year after his contract was meant to expire.1

Excerpt of a 1717 tax list for Perquimans County listing "Sanders the Indian." Courtesy of North Carolina State Archives.

While other American Indians might have deferred to their tribal authorities to appeal to the colonial government on their behalf, Sanders defended himself before the Perquimans County Court and won his own freedom. After the trial, Sander continued to live in Perquimans, where he resided independently through 1717.

Cases like Tom Harriss’ missing hog demonstrate how American Indians and colonists formed shared communities.

American Indians often appeared in colonial court proceedings even if they were not directly involved in the suit. For example, an American Indian named Tom Harriss featured prominently in a defamation suit between John Jennings and Matthew Winn. Jennings accused Winn of being a hog thief, but Winn vindicated himself when he proved he had not stolen anything. Instead, he had been helping Tom Harriss recover a pig that had escaped from Harriss’ farm and gotten onto Jennings’ property.

As the trial evidence demonstrated, Harriss had purchased the hog in question from Thomas Barecock. When the hog escaped, Harriss again depended on Barecock to help him locate and recapture the animal. In this instance Harriss not only cooperated with his colonial neighbors enough to broker a livestock trade, but he also relied on his neighbors to help find the hog too.

Small interactions like these, while relatively inconsequential, demonstrate how some American Indians and Europeans cooperated and lived alongside one another in early North Carolinian colonial society.

Tom Harriss, Matthew Winn, and other colonists would have kept hogs that looked like this one, illustrated on a 1733 map of North Carolina by Edward Moseley. Courtesy of East Carolina University Digital Collections.

When American Indians faced criminal charges, could they expect a fair trial?

When a colonial court charged an American Indian with a crime, it was not a foregone conclusion that the all-white colonial jury would pronounce the American Indian guilty. Instead, in many cases, the jury carefully weighed the evidence, not allowing cultural or racial prejudices from influencing their verdict. Perhaps no trial involving an American Indian better illustrates this than the 1722 case of John Cope, a Tuscarora man charged with burglary. But what crime had Cope committed?

During the early hours of one morning in August 1722, John Cope was drunk. It was late summer, where the mornings before sunrise are especially brisk and Cope hoped to find somewhere quiet where he could warm up and sleep for a few hours. Somewhere in Bertie County near Salmon Creek he found just the spot—a large secluded home with a prominent fireplace. Cope opened a window in the home’s living room and climbed in, content to take a nap near the fireplace.

Little did Cope realize, however, that this was no ordinary house. In fact, Cope had broken into what was perhaps the most important home in the colony—that of acting colonial governor Thomas Pollock.

The noise from Cope’s unorthodox entry into the home (along with perhaps a little snoring) awoke the Pollock home’s residents, who quickly evicted Cope from his warm spot on the foyer floor.

Within a few days Cope found himself on trial before an all-white jury of the North Carolina Court of Oyer & Terminer for burglary. Cope could have faced execution or banishment for the crime, but the jury, carefully examining the facts of the case, determined that Cope had not stolen anything, nor had he intended to do so. They pronounced him not guilty, and he was allowed go free.

An all-white jury was just one of the many obstacles American Indians faced when interacting with the NC colonial court system as individuals. Still, Cope's case demonstrates that coloial juries still had the ability to focus on fact without allowing prejudices to influence their verdicts.

As tribal autonomy waned, American Indians also used the colonial court system to settle interpersonal disputes, like debt.

As the colonial court system grew during the 1720s and 1730s, more people, both colonists and American Indians, began to rely on the court. In the 1733, John Robins, a Chowanoke Indian, took out a loan of eight pounds and ten shillings from Thomas Durant, likely a member of the Yeopim Nation. When Robins failed to pay back the debt, Durant filed a suit in the Chowan County court to recover the money. Robins failed to appear, and the case dragged on for several years.

The suit by its nature as a simple debt case is not particularly remarkable, but it still tells historians today a great deal about American Indian society of the time.

Robins and Durant brokered their deal through the format of an English legal document even though seemingly neither of them could read or write in English. They, along with their witnesses, came before the Chowan County clerk or another local colonial official to make a formal agreement, a practice outside the norm of traditional American Indian custom. In addition, they described their debt not in terms of tangible goods such as deer skins, beads, or shells, but in North Carolina currency—another sign of their dependence on the existing colonial court system.1

Robins’ and Durant’s reliance on the colonial court system suggests that they lacked confidence in preexisting American Indian governance. Neither Chowanoke nor Yeopim leadership, so it seems, had the power to enforce the agreement. The original document, as well as the transcription, are shown below.

February the 8—1733/4

This shall oblige me to pay or Cause to be paid to Thomas Duern Indian order the full sum of Eight Pounds Tenn Shillings Currant Bill money of North Carolina for Value Recd. as Wittness my Hand

his

John X Robin Indian

mark

his

John D Martin

mark

his

James J Bunats

mark

Charles B Beasely Indian

his mark

For this exhibit, as well as all other content on MosaicNC, editors use the term "American Indian" rather than other terms such as "Native American," "Indian," or "Indigenous." The North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs and the North Carolina American Indian Heritage Commission both also prefer the term "American Indian." Whenever possible, however, the editors strive to refer to culturally distinct groups of native people by their appropriate tribal names.

For more information on MosaicNC's editorial policies for American Indian terminology, see our Editorial Statement on American Indian Terminology.

- Kirsten Fischer, Suspect Relations: Sex, Race, and Resistance in Colonial North Carolina (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002) 48.

- Michelle LeMaster, “In the 'Scolding Houses': Indians and the Law in Eastern North Carolina, 1684—1760,” North Carolina Historical Review, 83:2 (April 2006) 226-228.