Self-emancipation refers to “the act of an enslaved person freeing themself from the bondage of slavery.”1 One of the most common means of self-emancipation amongst enslaved people was running away. For the enslaved, the physical act of leaving an enslaver’s property was a means of exerting control over their own bodies and circumstances. By pursuing freedom on their terms, enslaved people asserted their personhood in spite of a system of bondage meant to keep them down.

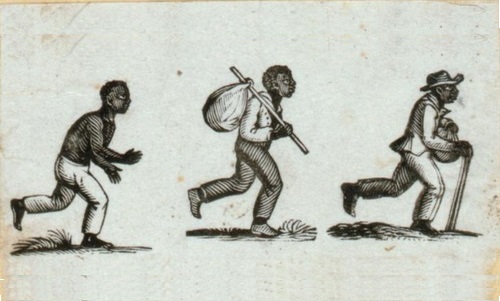

Engraving of three African American men running. By running away, or self-emancipating, enslaved people claimed freedom for themselves. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Many enslaved individuals pursued freedom by running away from their enslavers' plantations.

Running away from their enslavers’ plantations was a common, though dangerous way, that enslaved people pursued freedom. One North Carolinian that took this path was Charles Thompson, or “Scrub,” as he was known to his enslavers.

Prominent merchant Richard Bennehan of Orange County purchased Thompson when Thompson was just twelve years old. Enslaved, Thompson was forced to labor at Bennehan’s Snow Hill Plantation, and it was not long before Thompson established a reputation for himself as someone that would resist the confines of his bondage. In 1776 with the chaos and disorder American Revolution looming, rumors swirled amongst enslaved about the possibility of running away. At this time, Bennehan advised his overseers to keep a close watch on Thompson in particular, then aged seventeen.

Finally in 1784, when Thompson was twenty-five, he seized his opportunity and ran away. In a wanted ad Bennehan published in local newspapers, he stated that Thompson might have headed for Virginia, but if that was true, it does not appear Thompson was ever captured and reenslaved.2 By leaving the bounds of the plantation on his own accord, Thompson successfully seized his own freedom.

One of the few enslaved dwellings still standing at Richard Bennehan's Stagville plantation, from which Thompson made his escape. Courtesy of Historic Stagville.

Not all runaway attempts were successful. Still, some people resisted enslavement, no matter the cost.

Many enslaved people tried to run away, but not everyone was successful. Yet when faced with the prospect of capture and reinslavement, runaways like Cudgo refused, making a dramatic and permanent choice to remain free of bondage.

Sometime prior to October 1768, Cudgo ran away from his enslaver, William Campbell, in New Hanover County. At first it seemed as though Cudgo would be able to maintain his freedom. However, after Cudgo was absent from the plantation for some time, Campbell had Cudgo outlawed, meaning he was wanted dead or alive.

After intensive search, somewhere along the banks of the Northeast Cape Fear River, a slave patrol closed in on Cudgo. The patrollers intended to reenslave him. If Cudgo resisted capture, he’d be met with violence in return. Perhaps feeling cornered and desperate, Cudgo opted to jump off a bridge into the rushing waters below, where he subsequently drowned. For some like Cudgo, suicide was a better option than returning to bondage.

With its marshy banks, strong currents, and underwater obstructions, the Cape Fear River can be dangerous for swimmers. Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Not all enslaved people ran towards freedom. Some ran towards family instead.

One common goal of running away was freedom, but as Scipio’s story demonstrates, enslaved individuals ran away for a wide variety of reasons. Scipio, an African American man residing in Bertie County, was enslaved by Samuel Scollay. In 1741 Scipio left his enslaver’s plantation, but instead of seeking freedom for himself, he ran to the plantation of another enslaver, Benjamin Hill.

Scipio resided, and presumably labored, at Hill’s plantation for over a year before Scollay pursued legal action, demanding Scipio’s return. Legal records are scattered and incomplete, but it does not appear that Scollay’s petition was successful. Scipio remained enslaved by Hill, not Scollay, for the rest of his life. But what could prompt Scipio to leave one enslaver for another on his own accord? We can’t say for certain, but Hill’s will, dated less than a decade later, may provide some clues.

Scipio, it appears, had family that were also enslaved by the Hills, namely a wife named Dinah and two children, Scipio Jr. and Nancy. While Scipio could have made his escape from Scollay’s plantation and headed north towards a life of freedom, instead he pursued a separate path, one where he could live as a family with his wife. Freedom, it is clear, had different meanings for different individuals.

- Steward Henderson, “Self-Emancipation: The Act of Freeing Oneself from Slavery,” American Battlefield Trust, 25 March 2021, (accessed 5 March 2025).

- Richard Bennehan, "Thirty Dollars Reward," North Carolina Gazette (New Bern, NC) 2 September 1784.