Exhibit Sections

Image

Beyond Apollo

All around the country, the successes of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs played out in real time on living room television screens. For the first time in history, a generation came to maturity in a world in which space travel was considered an ordinary part of human existence. Young boys and girls began imagining themselves not just as Crayola-colored doctors, soldiers, and presidents, but also as astronauts, as brave explorers of a new frontier.

The influences of NASA’s golden era on the state’s citizenry can still be found today. With the arrival of the space shuttle program, North Carolinians finally started seeing their own among the high-profile astronaut crews, a trend that continues to this day.

Image

First Astronaut from North Carolina

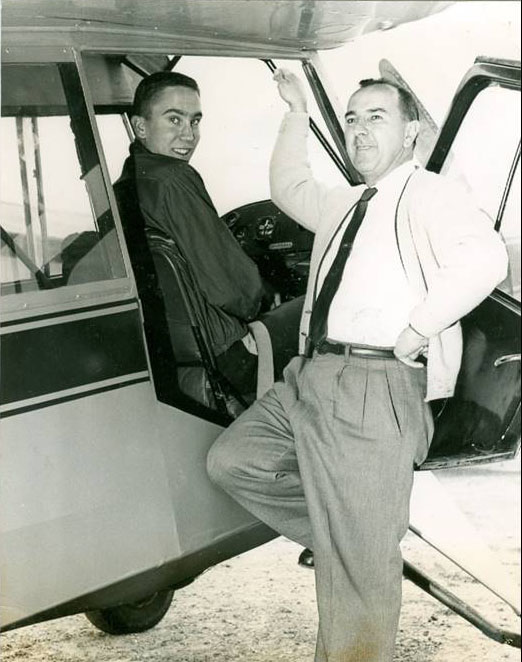

William E. Thornton is arguably North Carolina’s first homegrown astronaut. (Though Charlotte-born Charlie Duke’s selection for the astronaut program preceded Thornton’s by seventeen months, Duke was raised in his parent’s home state of South Carolina.) Born and raised in Faison, Thornton attended UNC Chapel Hill, where he received a bachelor’s in physics in 1952 and a doctorate in medicine in 1963. During his time with the U.S. Air Force, Thornton learned to fly jet aircraft and completed Primary Flight Surgeon’s training, setting a solid foundation for his career in space medicine research.

NASA selected Thornton as a scientist-astronaut in August 1967. During his twenty-six years with the nation’s preeminent space program, Dr. Thornton focused his work on the effects of space on the human body, particularly a condition known as “space adaptation syndrome.” To counteract the effects of weightlessness, Dr. Thornton developed several monitoring and exercise devices. He is perhaps best known for inventing a treadmill that can be used in space to help prevent muscle atrophy. The highlights of his career, however, came in the mid-1980s when he crewed space shuttle missions STS-8 and STS-51B aboard the Challenger, logging a cumulative 313 hours in space.

Image

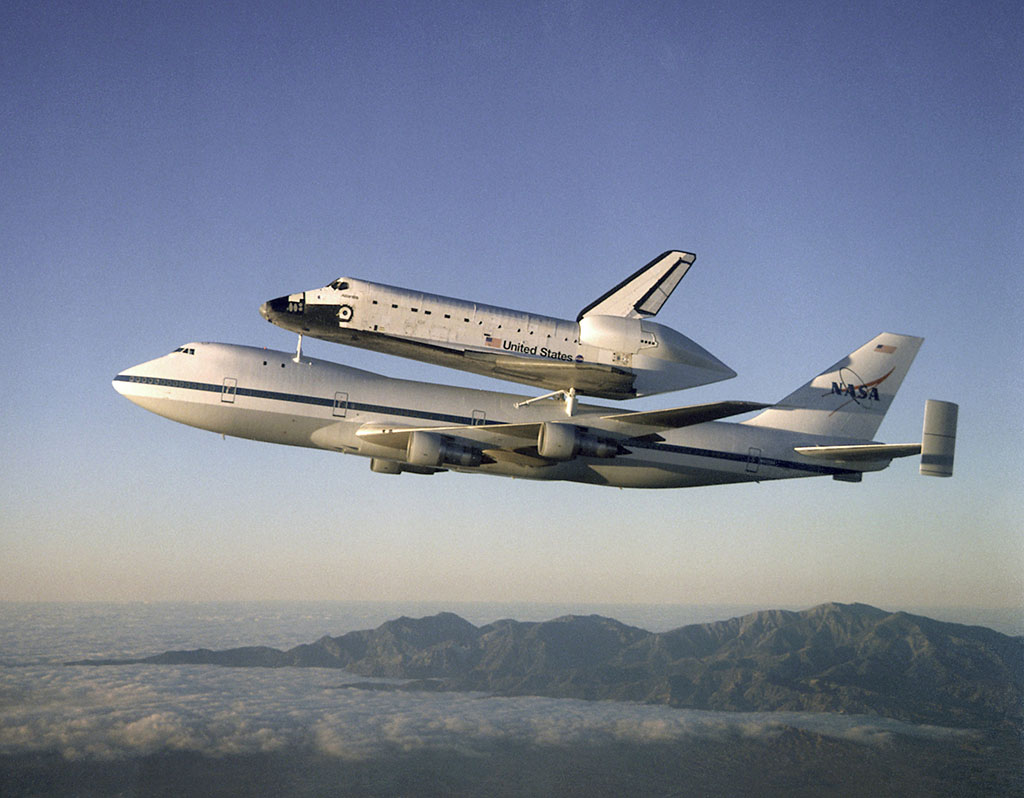

Shuttling the Shuttle

One of the more interesting facts about the space shuttle is that it essentially is a big glider. The vehicle had no real thrust capabilities of its own, relying instead on the Saturn booster system to escape Earth’s gravity. Though the shuttle could land much like a plane on a runway, it could not lift off from a runway under its own power. NASA officials faced one huge question: how do we shuttle the shuttle between the landing and take-off sites?

Wadesboro native and NASA engineer John W. Kiker had the answer. Using scaled, remote-controlled models, Kiker set about proving that the shuttle could be safely and more affordably transported by mounting it to the back of a modified Boeing 747. The NASA community was skeptical at first, but they gave Kiker the room he needed to develop the idea. Kiker’s “piggyback” plan became reality on February 18, 1977, when the shuttle Enterprise was mounted atop a 747 and carried into the sky for its first “flight.”

Two specially modified 747s, known as the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, ferried shuttle vehicles through the entirety of the program. The final piggyback flight occurred in 2012, when one of the planes carried the Endeavour from Florida to California for retirement.

Image

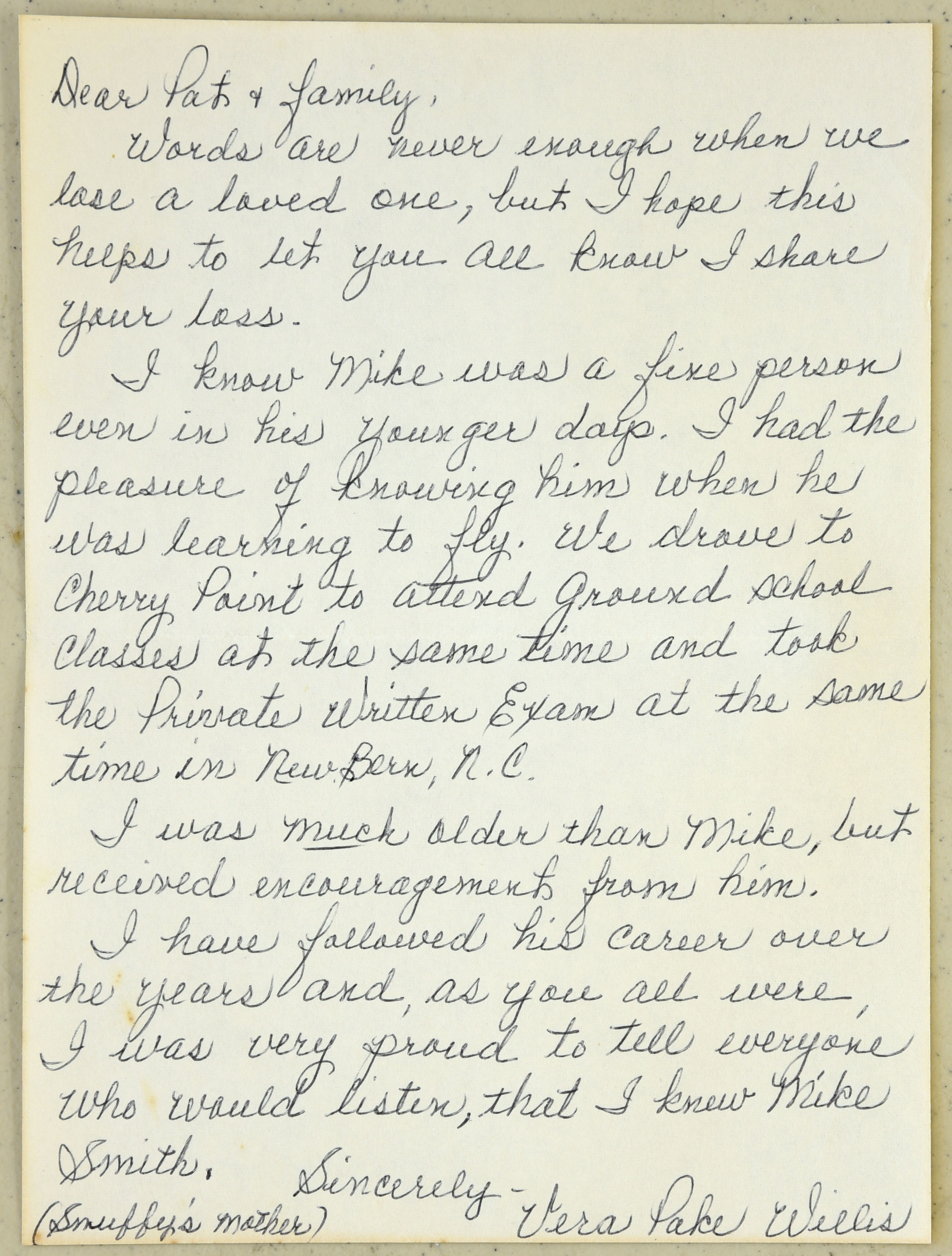

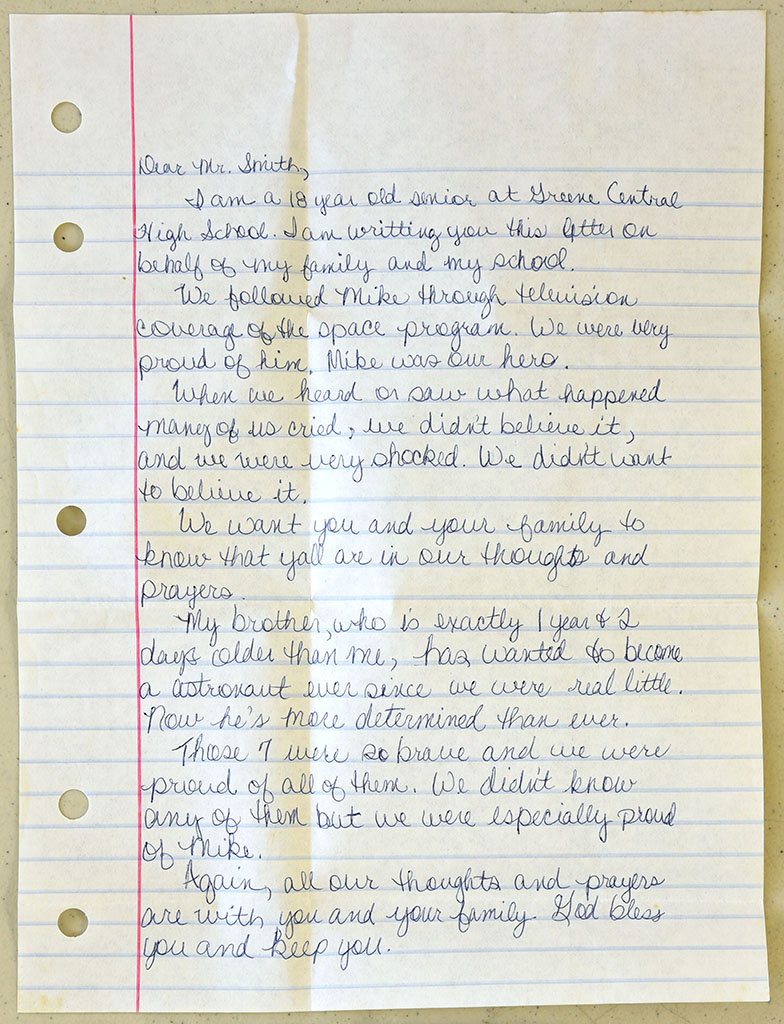

A Nation in Mourning

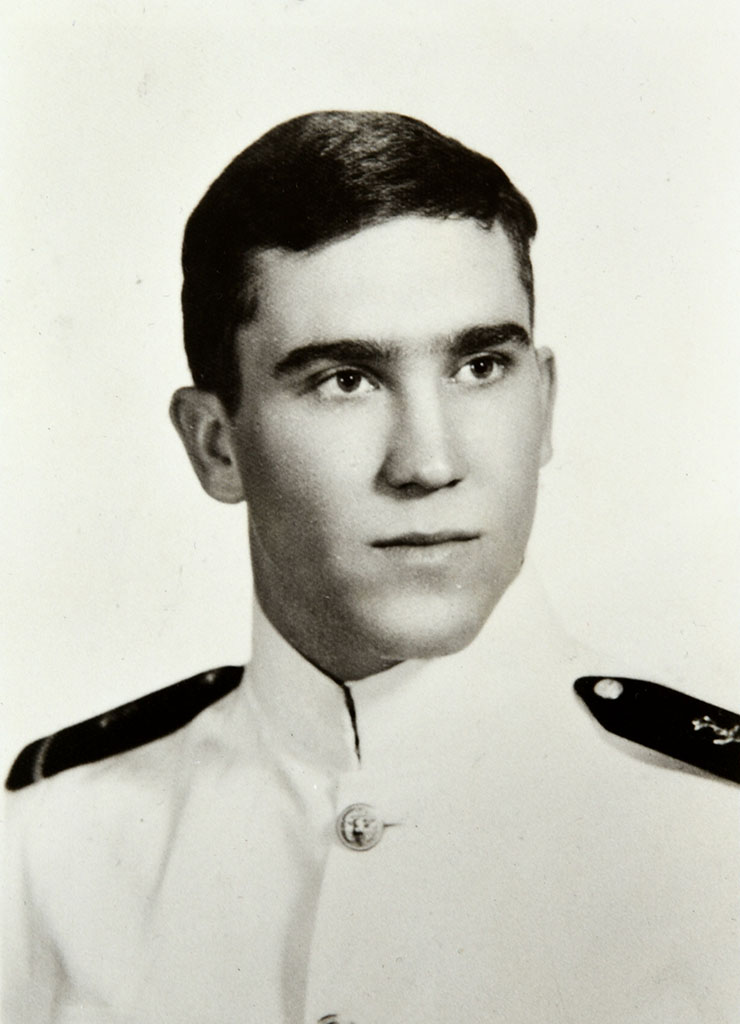

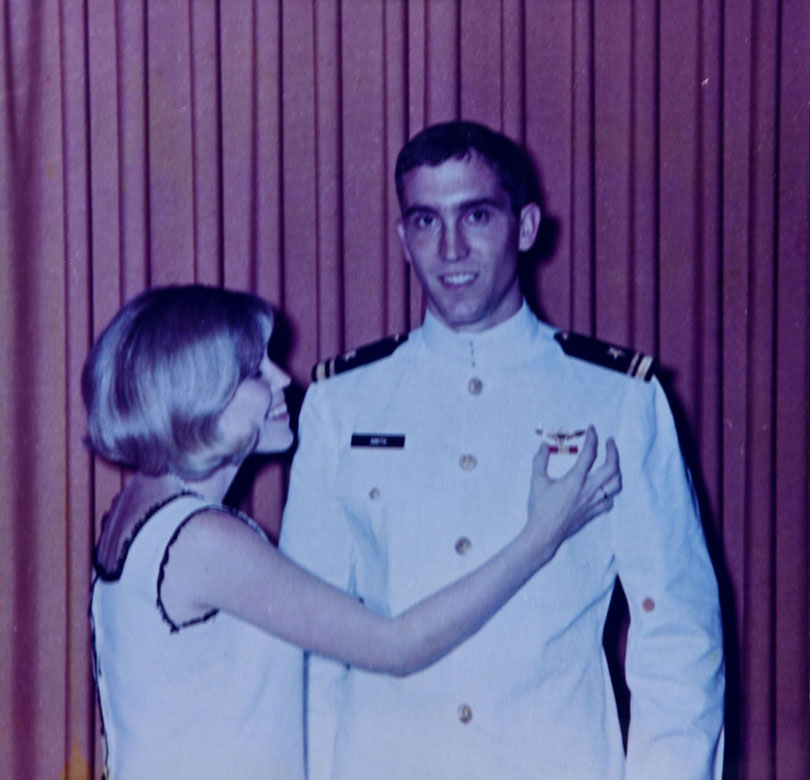

Beaufort native Michael J. Smith was just twenty-four when he watched Neil Armstrong take man’s first step on the Moon. Right then and there, he determined to become an astronaut. A meritorious career in the Navy followed, during which Smith learned to fly 28 different aircraft, flew 198 missions in Vietnam, and logged 4,868 hours of flight time.

In May 1980, he was accepted as an astronaut candidate and qualified as a shuttle pilot the following year. The call Smith long awaited finally came in 1985 when he was tapped to pilot the Challenger on its tenth mission. Tragically, the flight proved to be both Smith’s first and last. Just seventy-three seconds after launch on January 28, 1986, an O-ring seal in one of the Challenger’s two solid rocket boosters suffered a critical failure, leading to the disintegration of the shuttle over the Atlantic Ocean. The lives of all seven crew members were lost, including that of Mission Specialist Ronald E. McNair, a North Carolina A&T State University alumnus from South Carolina.

To date, Smith is one of twenty-four American astronauts to have lost their lives in the line of duty. In recognition of his sacrifice, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 2004.

Image

The Next Generation

Following the tragic loss of the Challenger on that fateful January day in 1986, President Ronald Reagan, in a brief but powerful address, paid homage to the crew and made a solemn promise to the American people: “The future…belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we'll continue to follow them.” And follow them we have, as North Carolinians watched with pride the preparations of one of our own to go to space.

Though born in Michigan, Christina Hammock Koch considers Jacksonville, North Carolina, her hometown. She is a proud alumna of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics and North Carolina State University, where she earned bachelor degrees in electrical engineering and physics and a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering. Koch, who was selected for astronaut training in June 2013, is currently serving as a flight engineer for Expedition 59 and 60 aboard the International Space Station.

Exhibit Text