Life on the Western North Carolina Railroad was often painful and exhausting for incarcerated people. When they were not working long hours on the railroad, they were confined in crowded prison labor camps. The grueling work and poor living conditions took a toll on their health. Many incarcerated people fought back against the system that exploited them.

Incarcerated workers and guards on the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1878-79. Courtesy of the Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library.

Incarcerated people worked long days doing difficult, dangerous labor to construct the railroad. They used explosives along the mountainsides to create cuts and tunnels and then broke up the rock and debris by hand using picks and shovels. There was often a shortage of mules and horses, so men pushed wheelbarrows and pulled carts to remove the heavy loads. Many incarcerated workers died or were injured in explosion accidents, rockslides, and cave-ins.

Incarcerated women and girls, as well as some men and boys who were sick or injured, were put to work in the prison labor camps. There, they cooked meals, mended and laundered clothes, and maintained the sleeping quarters. Some able-bodied men and boys also worked in the camps cutting wood and doing other necessary tasks.

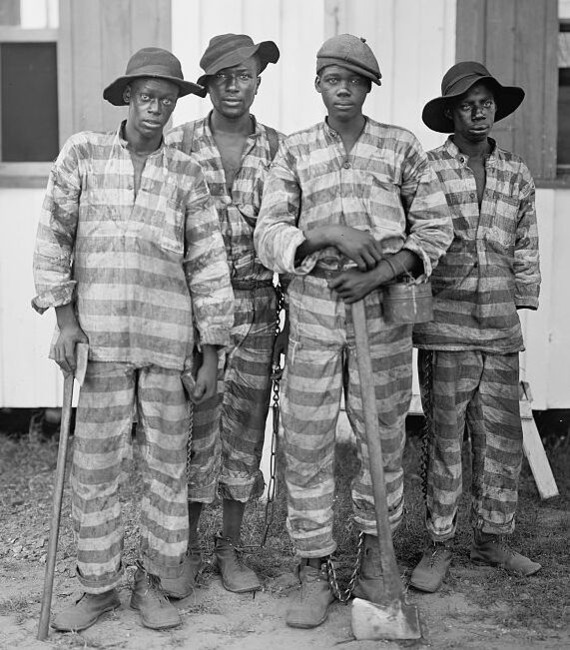

To prevent escape, some incarcerated people were forced to wear a ball and chain or shackles while they worked and, even sometimes, while they slept. At other times, guards shackled men and boys together at the ankles in a “chain gang.” The state government also permitted the guards and overseers to whip incarcerated workers using a rod or leather strap. Under the “trusty” system, some prisoners who were deemed unlikely to make an escape attempt were allowed to move around without shackles or constant supervision from guards.

Incarcerated workers on the Western North Carolian Railroad loading debris onto a gravel train in an area known as Mud Cut. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library.

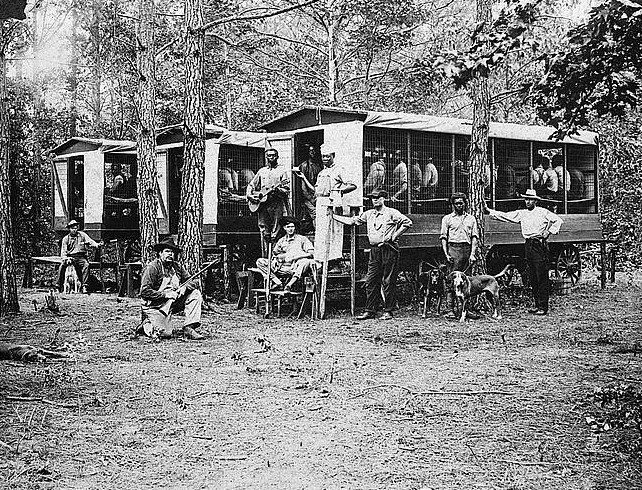

In labor camps throughout the south, such as this one in Oglethorpe, Georgia, guards watched as incarcerated labrorers performed backbreaking work. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Incarcerated workers such as these four loggers in Florida often labored while chained together to prevent escape attempts. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Prison labor camps, also referred to in the historic documents as “convict quarters” or simply “stockades,” were built along the railroad corridor to house incarcerated workers. Camps could hold hundreds of workers at a time. In other cases, prisoners were housed temporarily in train cars. The camps usually included separate sleeping quarters for male prisoners, female prisoners, and guards, as well as outdoor kitchen areas, makeshift hospitals, and work areas for blacksmithing, woodcutting, and other tasks needed to keep the work crews supplied.

Incarcerated laborers and guards standing along the Western North Carolina Railroad in front of the Swannanoa or “Top of the Mountain” Stockade, a prison labor camp near Ridgecrest, NC. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library.

A group of incarcerated laborers at a work camp in Mississippi wash their clothes in communal basins. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

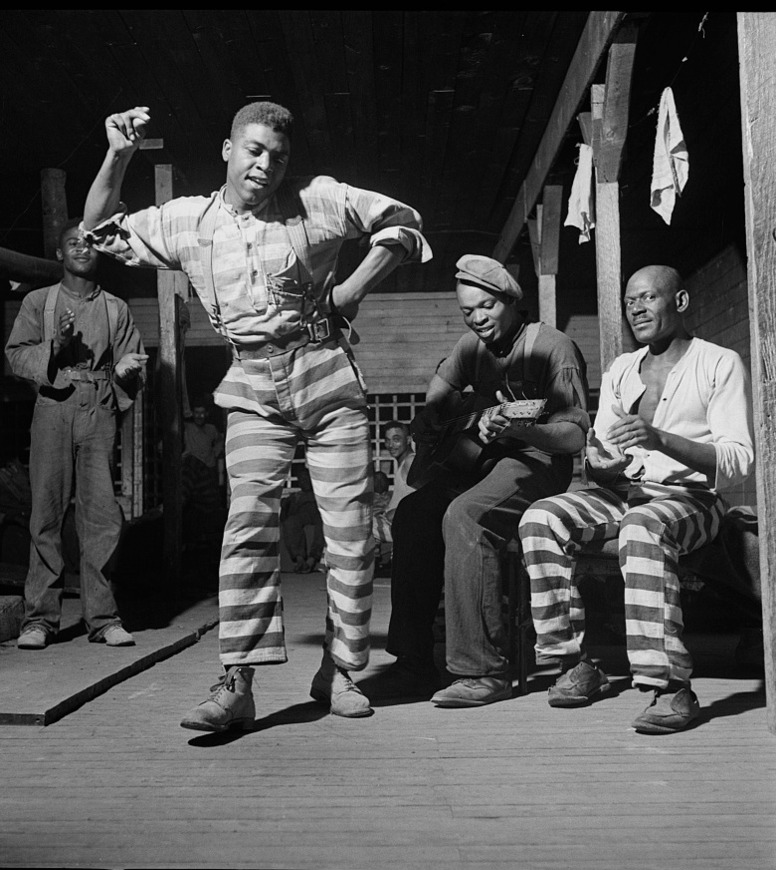

The Swannanoa Stockade was one of the largest of these camps and was located just east of the 1,832-foot Swannanoa Tunnel. This tunnel inspired the folk song by the same name, sometimes also called “Asheville Junction,” which is thought to have originated with the imprisoned workers themselves as a hammer song they sang while working. Prisoners were said to have played instruments and sing “freely” on Saturdays nights and Sundays, and that local community members would come to the camps to hear the music they made.3

The lyrics of many versions of “Swannanoa Tunnel” recall the dangers, the severity of the elements, and the specter of death:

One incarcerated man dances while another plays guitar. From a camp in Greene County, Georgia, in 1941. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The injuries, illnesses, and psychological traumas incarcerated railroad workers suffered often had life-long consequences. In an 1879 report, railroad and penitentiary employees testified that prisoners were “not sufficiently clad in underclothing” and that the general supply of clothing was not sufficient, especially bed clothing. One interviewee stated that “The rations furnished at these quarters are ½ pound of bacon and 1 ½ pounds of corn meal, and it is not sufficient; the meat is barely sufficient and the meal is less so.”

Some incarcerated people developed scurvy, a painful illness resulting from a prolonged lack of vitamin C, because the railroad officials did not provide fruits or vegetables. Viruses and bacterial infections also spread among incarcerated people in labor camps due to crowded sleeping areas, unsanitary conditions, and exposure to severe weather. Doctors working at the state prison said that incarcerated people were “returned from the railroads broken down and hopelessly diseased” and with “shattered constitutions.”

Cramped living conditions and poor ventilation meant that incarcerated laborers often suffered from diseases such as pnemonia and tuberculosis. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Workers on the Western North Carolina Railroad found many ways to resist their incarceration and mistreatment. Some incarcerated people escaped and were never found, while others were recaptured. Many were desperate for freedom and made multiple escape attempts. In several instances, workers tried to overpower guards and seize their guns. Around 150 incarcerated people joined together in an uprising against the guards on April 15, 1877. That night, nine men were killed, and fourteen others were injured before guards regained control. Between 1875 and 1890, at least 565 escapes were attempted.

Prison work camps often kept packs of attack dogs, trained to track and find prisoners who tried to escape. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

- The banner for this exhibit, a photograph of incarcerated workerns on the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1885, is courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- The banner for the subheadings in this exhibit, a map of the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1881, is courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

- Kevin Kehrberg and Jeffery A. Keith, "Somebody Died, Babe: A Musical Cover-Up of Racism, Violence, and Greed," Bitter Southerner,4 August 2020. (Accessed 25 April 2025).

- Biennial Report of the Board of Directors, Architect and Warden, Steward and Physcial of the North Carolina Penitentiary for the years 1879-180, pg. 8. Wilson Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.