The Swannanoa Tunnel on the former Western N.C. Railroad in 2023, photo by Cayla Colclasure.

The North Carolina government played a major role in funding the Western North Carolina Railroad’s construction and overseeing its management. The General Assembly saw the rail project as a necessary step in growing North Carolina’s industrial economy. The state adopted the convict leasing system to fuel this economic growth at the expense of predominantly Black laborers.

Charting a Railroad Through the Mountains

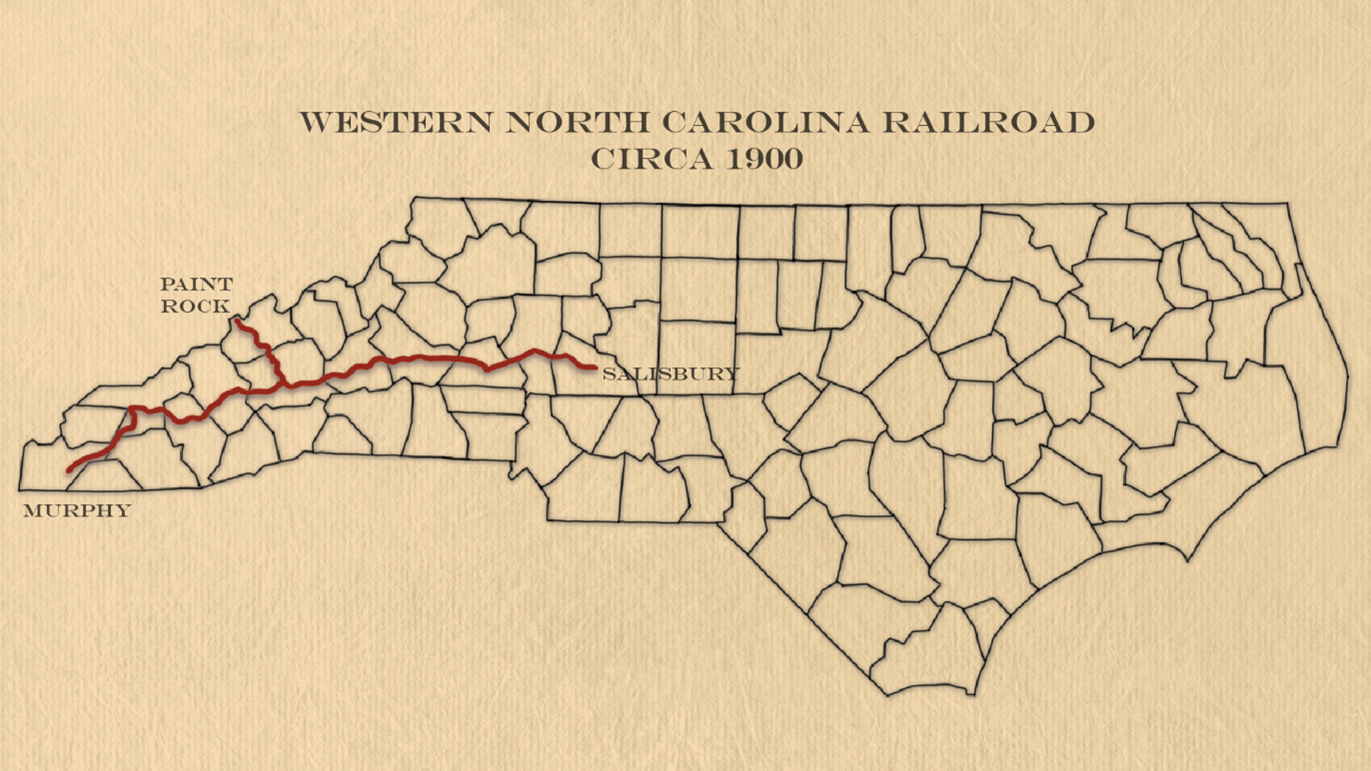

During the railroad boom of the 1800s, railroads transported goods and passengers all across North America more efficiently than ever before, ushering in an era of increased mobility and trade. The State of North Carolina completed the North Carolina Railroad from Goldsboro to Charlotte in 1854, but the mountainous western region of the state remained accessible only via stagecoach routes. Consequently, in 1885, the state founded the Western North Carolina Railroad Company to connect the western counties with the existing railway network. The proposed route would begin at Salisbury, head west to Asheville, and then split into two terminus points: one near Paint Rock and one near Murphy.

Map of the Western North Carolina Railroad, circa 1900. The route of the railroad, marked in red, extends west from Salisbury to Asheville, where it splits towards Murphy and Paint Rock. Created by Cayla Colclasure.

The Convict Leasing System

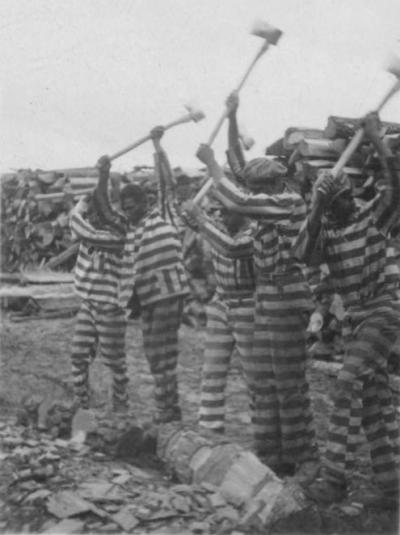

Constructing the railroads through North Carolina’s western mountains was dangerous work. Few men would work in such conditions for the low pay they were offered. As a result, the State of North Carolina conscripted laborers for the railroad— forcing first enslaved African Americans and later, after the abolition of slavery, prisoners, into construction. This conscription was referred to as "convict leasing."1

After the Civil War, the 13th amendment of the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime. Consequently, many former Confederate states, no longer able to force enslaved people to perform large, dangerous construction projects, began using prisoners. Companies rented incarcerated people as forced laborers from state penitentiaries and assumed responsibility for maintaining and guarding these prisoners.

Discriminatory laws and policies of the time disproportionately affected African Americans, meaning that the vast majority of prisoners, and therefore railway laborers, were Black. Though freed from slavery, African Americans prisoners toiled in the Western North Carolina mountains under slavery of another name. North Carolina officially ended its leasing system in 1933, though they continued to use incarcerated labor to build road networks throughout the state well into the mid-20th century.

Incarcerated workers chopping wood at Reed Camp, South Carolina, ca. 1934. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Completing the Railroad

Two state governors played influential roles in the history of the Western North Carolina Railroad: Zebulon B. Vance, who held office from 1877-79, and Thomas J. Jarvis, who served from 1879-1885. Vance, Jarvis, and the WNCRR president James W. Wilson were all veterans of the Confederate army, and both Vance and Jarvis were vocal supporters of white supremacy.2 Vance and Jarvis endorsed and oversaw a dramatic rise of Black North Carolinians being incarcerated during their tenures, as well as the expansion of convict leasing on the railroad, despite many appeals from reformers that working conditions were inhumane.

Vance and Jarvis’s official papers reveal that they were well aware of the violence prisoners experienced on the railroad but did little to stop it. On November 18, 1877, Wilson wrote to Vance saying, “You saw no doubt the statement of two convicts being shot by a guard, they had made a key and unlocked their shackles, this shooting has already has a salutary effect—work is progressing more favorably than ever.”3 Later, Governor Jarvis travelled to western North Carolina to investigate the railroad’s treatment of incarcerated workers, whereupon he excused the use of physical punishments on prisoners.

-

1855The NC Legislature charters the Western North Carolina Railroad. Until the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the railroad uses enslaved labor in construction.

-

1861-1865Progress on the Western North Carolina Railroad halts during the American Civil War. U.S. troops destroy portions of the railway.

-

1875The NC General Assembly passes “An Act to Authorize the Hire of Convict Labor In or Outside the State’s Prison, and to Regulate the Same,” which marks the beginning of the state’s convict leasing system. In the fall of 1875, the first group of imprisoned people are sent to McDowell County to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad.

-

1877At least 150 incarcerated people stage an uprising at a prison labor camp between Old Fort and the Swannanoa Tunnel to escape their imprisonment. Guards kill nine men and injure fourteen more.

-

1879Two crews of incarcerated men working from either side of the 1,822-foot Swannanoa Tunnel meet in the middle on May 11th. Shortly thereafter, a cave-in there kills twenty-one prisoners and one guard.

-

1882The Paint Rock railway branch is completed, connecting the railroad to the Tennessee state line. On December 30, in Jackson County, nineteen incarcerated Black men and boys working on the Murphy branch of the railroad drown after the flatboat ferrying them a short distance across the Tuckasegee River sinks.

-

1886-94The Richmond and Danville Railroad Company lease and operate the Western North Carolina Railroad. They oversee the completion of the Murphy branch in 1891.

-

1894The Western North Carolina Railroad, as well as the North Carolina Railroad and the Richmond and Danville Railroad, becomes part of the Southern Railway Company. The Southern Railway Co. operates until 1982, when it merges with the Norfolk & Western Railway to form the Norfolk Southern Railway.

- Further Reading on the Convict Leasing System: Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (Anchor Books, 2009); Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (New York: Verso, 1996); Matthew J. Mancini, One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996).

- C. Scott Holmes and Amelia O'Rourke-Owens, "Trespassing on White Supremacy: The Legacy of Establishment White Supremacy in North Carolina" NCL Rev. F. 100 (2021): 149; Paul Yandle, “‘The Relapse of Reconstruction:’ Railroad -Building, Party Warfare and White Supremacy in Blue Ridge North Carolina, 1854-1888” Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports, January 1, 2006.

- James W. Wilson to Zebulon B. Vance, 18 November 1877, Zebulon B. Vance Governor's Papers, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh.

- The banner for this exhibit, a photograph of incarcerated workers on the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1885, is courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- The banner for subheadings in this exhibit, a map of the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1881, is courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

.jpg)

.jpg)