The majority of incarcerated people on the railroad were Black men and boys. They worked alongside smaller numbers of Black women and girls, as well as white men. These people were from all across the state of North Carolina, and occasionally neighboring states like South Carolina and Virginia. Most of these individuals were convicted of crimes relating to poverty and lack of employment opportunities.

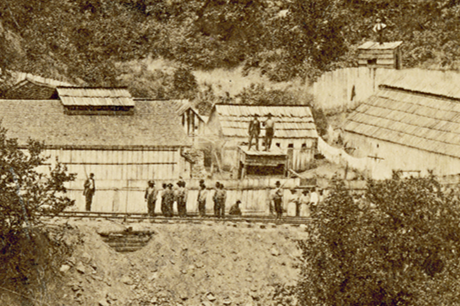

Incarcerated workers and guards on the Western North Carolina Railroad. In the foreground, several men stand to the left, and several women to the far right. Courtesy of the Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library.

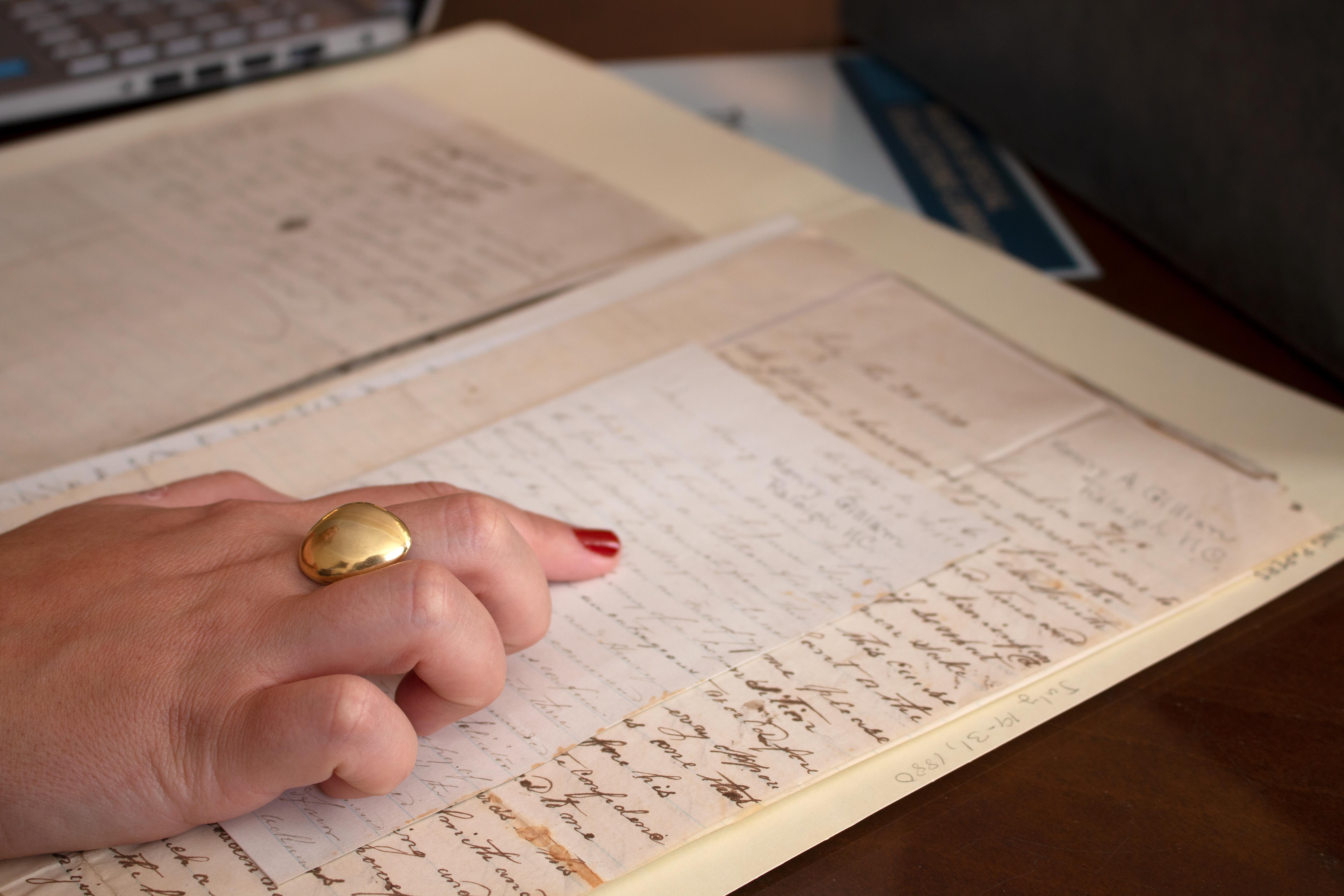

Despite rarely having first-hand accounts written by prisoners themselves, numerous archival documents can provide insight into who these incarcerated people were. Sentencing documents provide information about the crimes they were convicted of, whether they pleaded “guilty” or “not guilty”, and what judge and jurors were involved in their trial. The North Carolina State Penitentiary’s Descriptive Register is a book of tables with each prisoner’s name, age, place of residence, education, occupation, marital status, and even physical characteristics like height, weight, and the color of their skin, eyes, and hair. Prison department receipts tell us when individual people went from the penitentiary in Raleigh to various locations along the Western North Carolina Railroad.

The Register of Convicts and sentencing documents can help to identify the correct individual in federal census records, freedman’s bureau records, other government documents, and newspapers. Together, these sources can help us reassemble a sketch of a person’s life beyond incarceration.

A letter concerning Lucy Morgan, a woman imprisoned on the Western North Carolina Railroad, in the UNC Wilson Library Special Collections. Photo by Jess Abel.

William Anderson

William Anderson was an African American man born in Virginia around 1849. William may have been enslaved prior to the end of the Civil War. Later, he worked much of his life as a tenant farm laborer before eventually being able to purchase his own farm.

William married his wife, Fannie, in 1870, and the couple settled down in Sampson County, North Carolina. The couple had several children, including two daughters named Lucy and Rena. William was twenty-eight years old when he was charged with larceny on December 3, 1877. During his one-year prison sentence, he was sent to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. William was discharged from his prison sentence on November 3, 1878.

Though prison records state that William was illiterate when he was arrested, by 1900 he was able to both read and write. By 1920, he owned a farm in North Clinton, where his grandchildren, Ollie, James, and Joseph, lived with him. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 79 on February 22, 1926, and was laid to rest in South Clinton.

African American farmworkers in Ablemarle, North Carolina, 1881. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Laura Barrow

A young African American woman in a maid's uniform with a girl, circa 1904-1918. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Laura Barrow was an African American girl born around 1859 in North Carolina, possibly into slavery. Laura received little formal education in her youth, and from an early age she worked as a house servant. She reportedly sometimes used the alias “Laura Zegler.” Laura was convicted of larceny on May 16, 1873, when she was fourteen years old, and sentenced to four years of hard labor.

Sometime after 1875, Laura was sent to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. There, Laura worked alongside a group of women to cook, clean, launder, and mend clothes for the incarcerated men and boys doing railroad construction. Laura was discharged from her prison sentence on March 24, 1877, when she was eighteen years old.

Van Fuller

Van Fuller was an African American man born around 1857 in North Carolina. Van worked as a general laborer in Alamance county. At the age of twenty-one, on May 22, 1878, Van was convicted of larceny. He was sentenced to two years of hard labor and sent to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. He was released from his prison sentence on March 15, 1880.

In 1902, Van and his mother— “Lavinia” or "Winnie”— were arrested in connection with burning two barns in Hillsborough. Van fled north to Virginia but was captured by police and returned via train to North Carolina for trial. He was convicted of arson and sentenced to thirty years in prison, and his mother was convicted as an accomplice and sentenced to twenty years. Samuel P. Kirkpatrick, who owned one of the barns Van was accused of burning, was a former enslaver. One newspaper stated that “the motive for their crimes was revenge.” Van’s sentence was commuted by the state governor in 1917, when Van claimed he was around seventy years old.

African American man unloading a cart loaded with turpentine barrels, circa 1880s. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Jack McNatt

Photograph of a turpentine still, circa 1895. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Jack McNatt was an African American man born around 1844 in South Carolina. He spent much of his life in Robeson County, North Carolina. In 1874, the Wilmington Weekly Star reported that Jack had attempted to vote in an election, and Daniel McNatt challenged Jack’s ballot, getting it rejected. Daniel McNatt, who prevented Jack from voting, was a Confederate veteran and a former slave owner. Because they share the same last name, it seems likely that Daniel McNatt had been Jack’s enslaver.

Jack was accused of burning Daniel McNatt’s turpentine still in retaliation for the obstruction and was sent to jail in Lumberton. Jack was charged with burning the still on October 3, 1874, when he was thirty years old. He was sentenced to three years of hard labor and sent to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. He was discharged from the railroad on August 1, 1877.

Darry Woods

Darry Woods was an African American boy born around 1864 in South Carolina. Darry spent part of his youth in Columbus County, North Carolina. He was arrested at the age of fourteen in 1878, standing under five feet tall and weighing only 90 pounds. Darry was accused of stealing a pocket watch. While awaiting trial, he was also indicted for allegedly attempting to destroy a train by laying iron bars across the tracks. He was convicted of larceny and sentenced to seven years of hard labor on the Western North Carolina Railroad. He escaped from the railroad on December 9, 1881, and was recaptured on December 11, 1881. When Darry was around eighteen years old, he escaped again on May 20, 1882, and there is no record of his recapture thereafter.

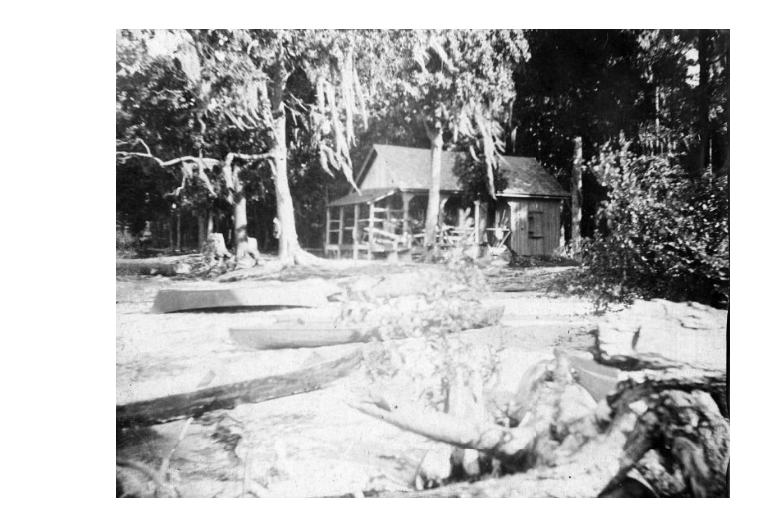

A house near Lake Waccamaw in Columbus County, perhaps similar to where Darry Woods would have resided, circa 1915. Courtesy of North Carolina Digital Collections.

Samuel Underwood

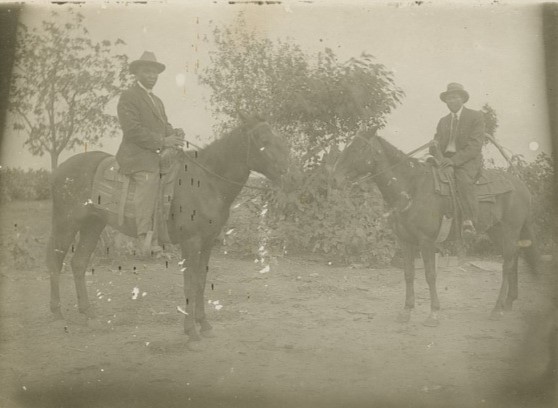

Two African American men on horseback during the late 19th or early 20th century. Underwood crafted saddles and harnesses such as those pictured. Courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Samuel Underwood was born around 1818 in North Carolina. Samuel was a biracial man, and prior to emancipation he was a free person of color. A skilled tradesperson, Samuel made and repaired leather saddles and harnesses. He lived with his wife, Mary, in Caldwell County, North Carolina.

Samuel was sixty years old when he was convicted of larceny on May 23, 1878. He was sentenced to two years hard labor on the Western North Carolina Railroad. After his release in 1880, Samuel and Mary moved to Boone (Watauga County), North Carolina.

Willis Garrett

Willis Garrett was an African American man born around 1853 in North Carolina. Willis lived in Northampton County with his wife and worked as a wagoner transporting goods. Sometime in his childhood or adolescence, Willis learned to read.

Willis was convicted of larceny on November 16, 1874, when he was twenty-one years old. He was sentenced to six years of hard labor and sent to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. Willis attempted to escape from the railroad alongside two other incarcerated men and was shot and killed by a guard on March 31, 1876.

African American man driving a wagon in Asheville, North Carolina, circa 1895-1910. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Parrish Ray

Parrish Ray was a biracial man born around 1858 in North Carolina, to his parents Levi and Judia Ray. Parrish had several siblings, including Stanly, Gracy, Francis, and Moses. He and his family lived in Durham, North Carolina. Parrish was convicted of larceny on May 13, 1878, when he was nineteen years old, and sentenced to one year of hard labor on the railroad. Parrish was released on April 18, 1879. He was shot and killed by a Durham police officer on February 7, 1887, when he was around twenty-nine years old.

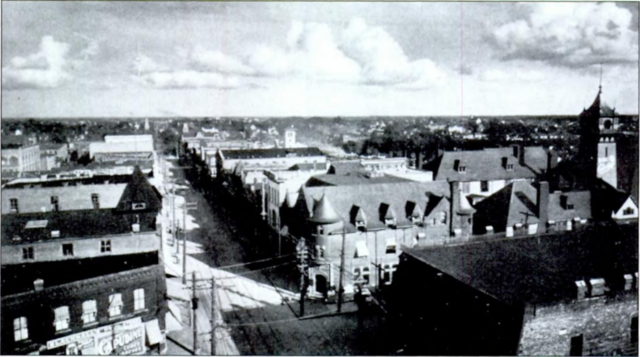

Skyline of Durham, North Carolina, circa 1905. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- The banner for this exhibit, a photograph of incarcerated workerns on the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1885, is courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- The banner for the subheadings in this exhibit, a map of the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1881, is courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

.jpg)

_0_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)