The 1916 Election

The War Governor: Thomas W. Bickett, 1917-1921

The 1916 Election

North Carolinians Head to the Polls

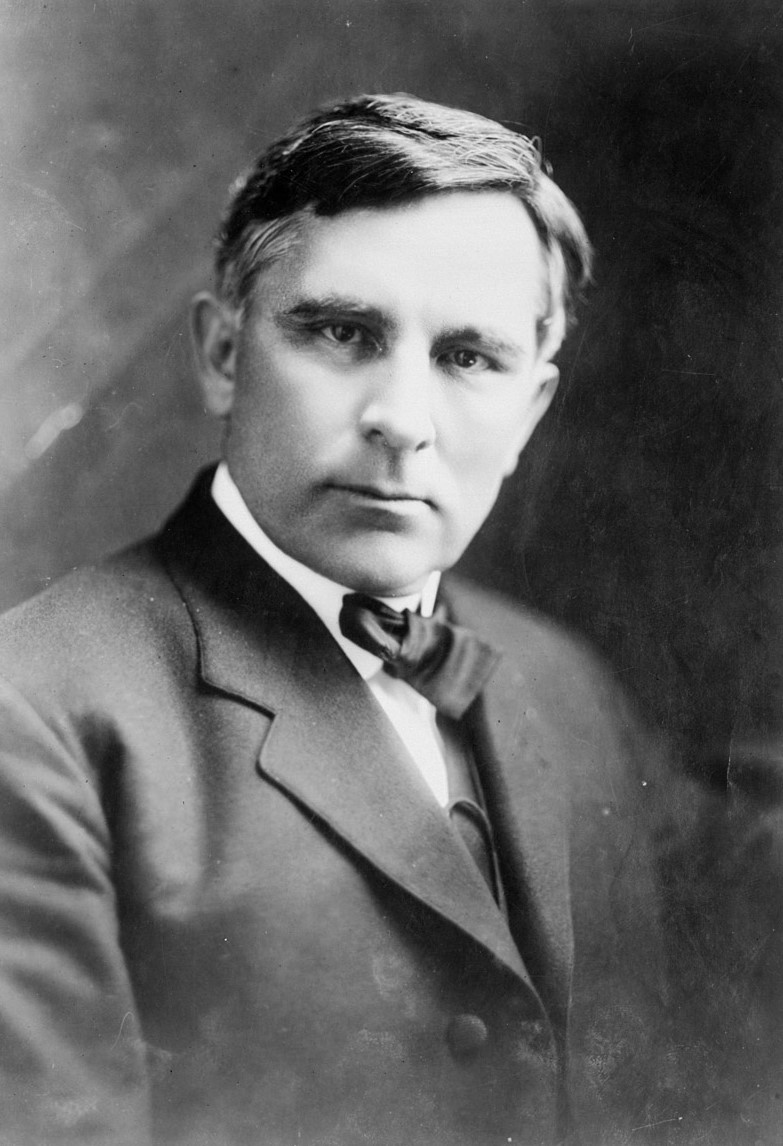

In the 1916 Democratic primary—the first legal primary held in the state—Thomas W. Bickett soundly defeated his opponent, lieutenant governor Elijah L. Daughtridge.1 With his party’s nomination secured, Bickett then set his sights on the general election, in which he would face Republican nominee Frank A. Linney. Linney focused his campaign on Democratic corruption and mismanagement, citing financial irregularities in recent state audits and the deplorable conditions of the Confederate Soldiers’ Home. Democrats took criticisms of the latter right on the chin, the press largely printing the damning reports of overwhelming fly, bed bug, and cockroach infestations then plaguing the home and its residents.2

In return, state Democrats branded Republicans as unpatriotic, corrupt, and eager to destabilize white supremacy, stoking racial fears at every possible turn. At the Democratic state convention in April 1916, United States Senator from North Carolina Furnifold M. Simmons decried the Republican Party as an “alien horde” that “burdened the state with debt, disgraced it with scandal and degraded it with negro rule.”3 Future Democratic governor Cameron Morrison urged voters in Guilford County to remain vigilant and steadfast. Any lapse in their support, he warned, would result in a return to “mongrelism, negro rule and incompetency.”4 In a widely circulated letter, state Democratic Party chairman Thomas D. Warren equated a Republican victory with the “restoration of Negro suffrage” and the institution of “Negro rule.”5

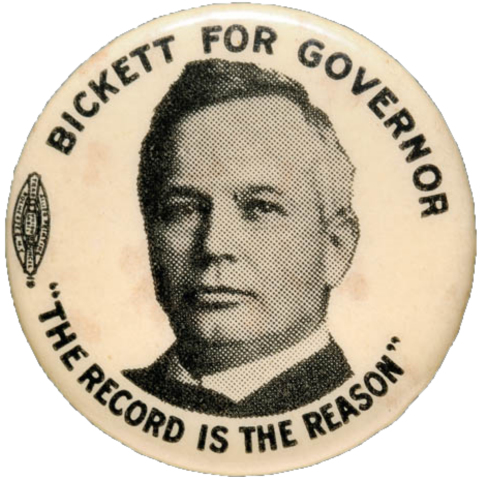

Campaign button bearing Thomas W. Bickett's likeness, name, and campaign slogan, circa 1916. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

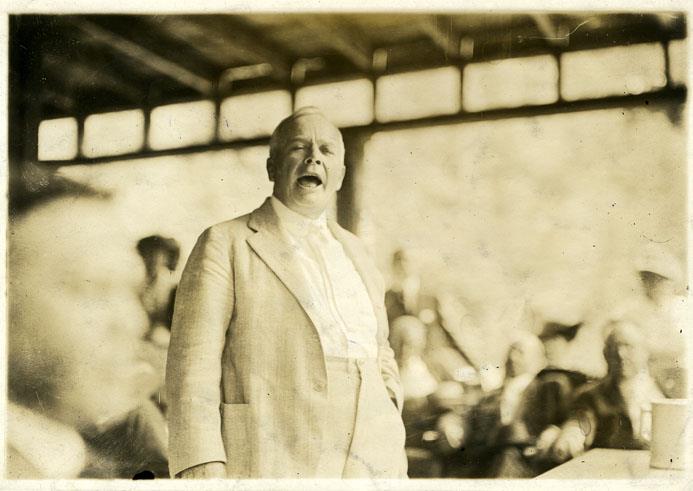

Governor Thomas W. Bickett delivers a speech at the Esmeralda Inn in Chimney Rock on July 4, 1918. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

For the most part, Bickett steered clear of race-baiting politicking, allowing Democratic peers to lead these kinds of craven attacks. In campaign speeches and public addresses, he chose instead to closely align himself with the policies of the Wilson administration, centering his talking points on foreign policy, the war, and domestic peace and prosperity.6 At every turn, he refrained from openly criticizing state Republicans and appealed to populist and progressive sympathizers—those who had helped install Republican politicians in 1896 and 1912, specifically—imploring them to return to the Democratic Party: “In the name of the family that has missed you I extend to you an invitation to come back to the old homestead. You are essentially of Democratic lineage.... Our doors swing wide to receive you.”7

If the politically centrist tone of his campaign wasn’t enough to convince fallen Democrats and moderate Republicans, Bickett could always rely upon his personable and affable nature to win voters’ hearts. Across the state, Bickett’s audiences could not help but fall in love with his keen wit, charm, and able storytelling, tools that he used to his advantage again and again. At Lexington on October 3rd, 1916, the many days of travel and long speeches began to catch up with him. With a “crippled voice,” Bickett began his address to the assembled crowd “slowly and deliberately” but eventually picked up speed and “soon had the audience roaring with laughter…or hanging almost breathless to catch [his] every word.”8 It was a scene that played out at campaign stops throughout the state. He was nothing if not a great speaker.

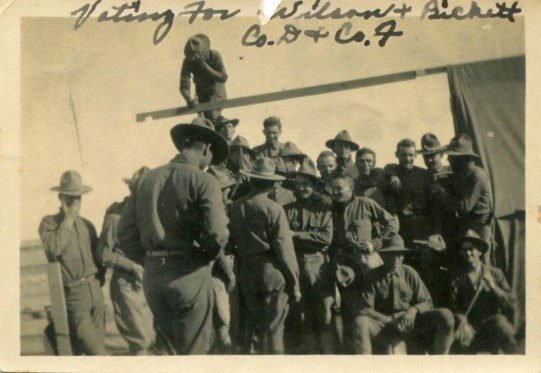

Support for the Democrat’s campaign was enthusiastic. Wilson-Bickett Clubs organized across North Carolina, in towns large and small, arranging speeches, rallies, barbecues, and voter registration drives. Club members in New Bern fabricated and displayed campaign signs riffing on Wilson’s reelection campaign slogan, a nod to the nation’s isolationist stance towards the war: “America First, vote for Wilson and Bickett.”9 On “Wilson Day”—October 28, 1916, ten days before election day—the clubs made one last push for the Democratic ticket, holding rallies to promote and celebrate Democratic gains made since the turn of the century.

On election day 1916, more than 167,000 eligible voters10—which included few men of color and no women—cast their ballots for Bickett, handing him the governorship by a margin of more than 46,000 votes.11 Linney humbly conceded, and Bickett accepted with grace:12

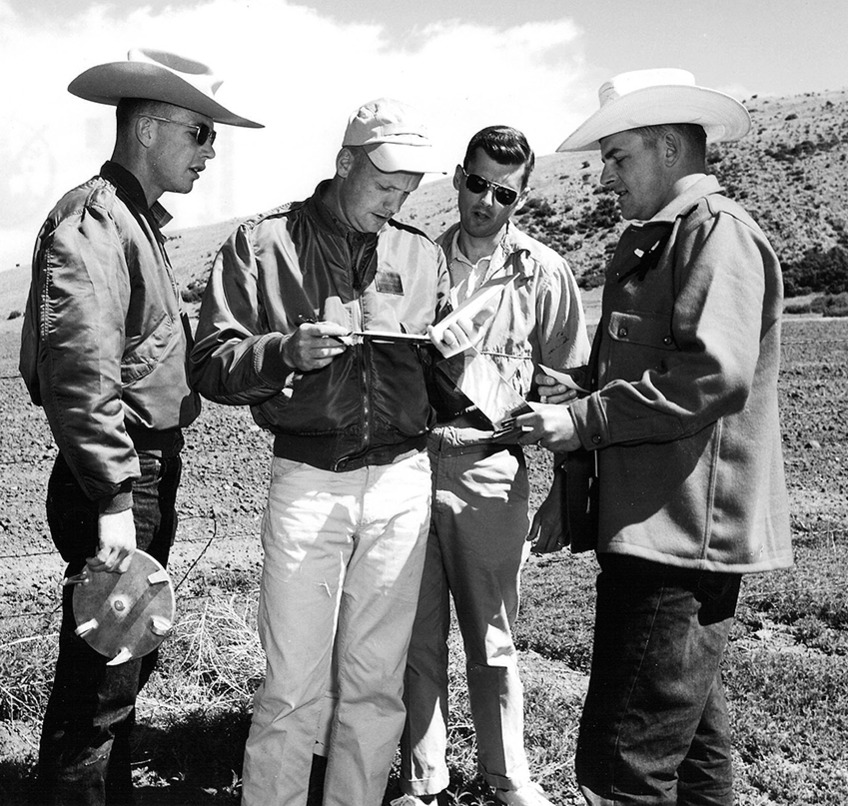

Members of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry cast ballots in the 1916 election while stationed at Camp Stewart near El Paso, Texas. Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina.

You have made a clean, strong and able campaign, and have given an elevated tone to the character of North Carolina political debate. You have won. Accept my congratulations.

Telegram from Frank A. Linney to Thomas W. Bickett, November 9, 1916

I thank you for your generous telegram. Your own campaign does you high credit, and I am grateful that our contest leaves no sting and no scar. Wishing you every happiness....

Telegram from Thomas W. Bickett to Frank A. Linney, November 9, 1916

Democratic Party Platform

Bickett’s victory ensured the fulfillment of the state’s Democratic Party platform as it stood in 1916: support for the good roads movement, improvements in public health, continued development of public education, recruitment of new businesses and capital investments for job creation, and increased support for agriculture and the rural communities that relied upon it.13

Democratic triumph additionally guaranteed—in explicit terms, no less—the continuation of white supremacy. “So long as the Democratic Party is in power,” the platform promised, “the people have assurance that this State shall be conducted by white men….” Strict, racially-motivated voting laws, established by a state constitutional amendment passed in 1900, stripped most Black men of the franchise. Sixteen years after its passage, Democrats doubled down on the measure, reaffirming their “confidence in the wisdom and justice of the suffrage amendment."14

Over the next four years, Bickett walked a fine line between progressivism and conservatism, championing advancements for the people of North Carolina while also maintaining well-established societal norms governing race, class, and sex. As a result, his decision-making as governor can be, at times, confusing to modern researchers. The same man who mobilized the National Guard against white lynch mobs also upheld and defended what he perceived to be the righteousness of white supremacy and racial segregation. He decried women’s suffrage as a threat to that white supremacy but ultimately called upon the North Carolina General Assembly to ratify the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution. He led the charge for more and better mental health facilities but also publicly advocated for the institution of a state-funded eugenics program to sterilize those he viewed to be “incurable mental defective[s].”15

1. Bickett prevailed over Daughtridge with a final count of 63,121 to 37,017. John L. Cheney, editor, North Carolina Government, 1858-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History, (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State, 1981), 1375.

2. Frank A. Linney, “Partial Press and Democracy,” Union Republican (Winston-Salem), 20 April 1916.

3. “Keynote Speech of the Raleigh Convention is Made by Sen. Simmons,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 April 1916.

4. “To Democrats: Charlotte Man Talked to Guilford,” Everything (Greensboro), 29 April 1916.

5. Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, The Nomination of Thomas D. Warren to be United States Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, 66th Cong., 1st sess., 1919, 35.

6. “Bickett Thrills Great Crowd of Alamance Democrats at Graham,” News and Observer (Raleigh), 20 Aug 1916; “Cheering Throng was at Ashboro (sic) Saturday to Hear T. W. Bickett,” Greensboro Daily News, 27 Aug 1916;” Governor-Elect Bickett Addresses the Democratic Voters of Nash County,” Graphic (Nashville), 31 Aug 1916.

7. “Bickett Speaks to Large Audience,” News and Observers (Raleigh), 01 Oct 1916.

8. “Bickett Arouses Davidson Farmers,” News and Observers (Raleigh), 04 Oct 1916.

9. “A Voice from Craven County,” Union Republican (Winston-Salem), 26 Oct 1916.

10. Suffrage law in 1916 extended the vote to an incredibly narrow portion of the state’s citizenry, the result being that the electorate was largely comprised of white males over the age of 21. To maintain eligibility, of-age male citizens were required to be literate, to pay a poll tax, to have no criminal record, and to acknowledge the “being of Almighty God.” To ensure that no illiterate white men were turned away from the polls, the 1900 suffrage amendment also instituted a “grandfather clause.” The clause allowed illiterate white men to cast a ballot if they, or a lineal ancestor, had registered to vote before January 1, 1867. R. D. W. Connor, editor, North Carolina Manual, Issued by the North Carolina Historical Commission for the Use of Members of the General Assembly, Session 1917 (Raleigh, NC: Edwards and Broughton Printing Company, 1917), 340-342; James L. Hunt, “Grandfather Clause,” NCPedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/grandfather-clause, accessed January 23, 2019.

11. Final tallies for Bickett and Linney are officially recorded as 167,761 and 120,157, respectively. Cheney, North Carolina Government, 1858-1979, 1409.

12. “Linney and Bickett Exchange Messages,” News and Observer (Raleigh), 11 Nov 1916.

13. Connor, ed., North Carolina Manual, Session 1917, 256-261.

14. Connor, ed., North Carolina Manual, Session 1917, 261-262.

15. Thomas W. Bickett, “Message of Governor T. W. Bickett to the General Assembly of 1919,” 9 January 1919.

Beyond Apollo

Beyond Apollo

Christina Koch is the most recent person from the Tar Heel State to make the trip to space. Here she is aboard the International Space Station on March 18, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

With the arrival of the space shuttle program, North Carolinians finally started seeing their own among the high-profile astronaut crews, a trend that continues to this day.

All around the country, the successes of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs played out in real time on living room television screens. For the first time in history, a generation came to maturity in a world in which space travel was considered an ordinary part of human existence. Young boys and girls began imagining themselves not just as Crayola-colored doctors, soldiers, and presidents, but also as astronauts, as brave explorers of a new frontier. The influences of NASA’s golden era on the state’s citizenry can still be found today.

First Astronaut from North Carolina

William E. Thornton is arguably North Carolina’s first homegrown astronaut. (Though Charlotte-born Charlie Duke’s selection for the astronaut program preceded Thornton’s by seventeen months, Duke was raised in his parent’s home state of South Carolina.) Born and raised in Faison, Thornton attended UNC Chapel Hill, where he received a bachelor’s in physics in 1952 and a doctorate in medicine in 1963. During his time with the U.S. Air Force, Thornton learned to fly jet aircraft and completed Primary Flight Surgeon’s training, setting a solid foundation for his career in space medicine research.

NASA selected Thornton as a scientist-astronaut in August 1967. During his twenty-six years with the nation’s preeminent space program, Dr. Thornton focused his work on the effects of space on the human body, particularly a condition known as “space adaptation syndrome.” To counteract the effects of weightlessness, Dr. Thornton developed several monitoring and exercise devices. He is perhaps best known for inventing a treadmill that can be used in space to help prevent muscle atrophy. The highlights of his career, however, came in the mid-1980s when he crewed space shuttle missions STS-8 and STS-51B aboard the Challenger, logging a cumulative 313 hours in space.

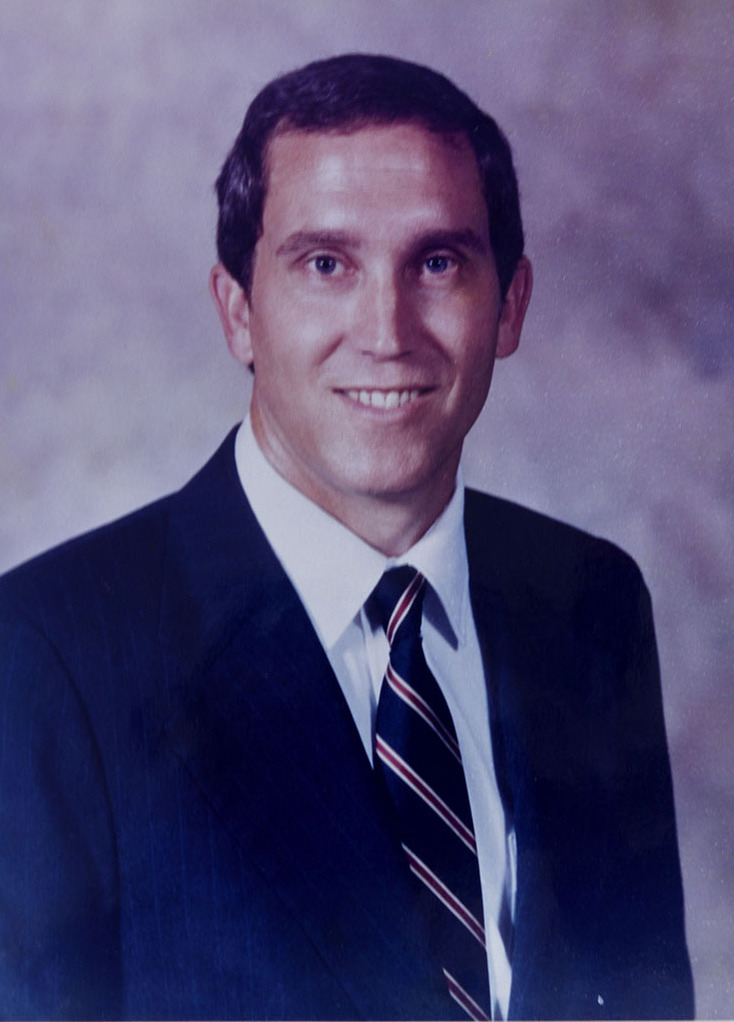

North Carolina native William E. Thornton was selected as a scientist-astronaut in August 1967. Courtesy NASA.

In the summer of 1972, Dr. Thornton took part in the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT). SMEAT sought to test medical equipment and gather data in preparation for Skylab. Here, Dr. Thornton (standing) is preparing Karol J. Bobko for an experiment that tested the effects of negative pressure on the lower body. Courtesy NASA.

Astronaut Dale Gardner assists Dr. Thornton in conducting an audiometry test aboard Challenger during STS-8 in 1983. Courtesy NASA.

Dr. Thornton took his first space flight aboard the shuttle Challenger on mission STS-8 in 1983. Courtesy NARA.

Dr. Thornton's second and final space flight occurred in 1985. This image captures him in the pilot's station of the flight deck of the space shuttle Challenger. Courtesy NARA.

Thornton wore this blue NASA flight suit during the Spacelab 3 mission in 1985. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Dr. Thornton monitors fellow astronaut Guion Bluford's use of the treadmill he designed for use in space aboard the shuttle Challenger in 1983. Courtesy NARA.

Over the course of his career, Wadesboro native and NASA engineer John Kiker made several iconic contributions to the American space program. Courtesy NASA.

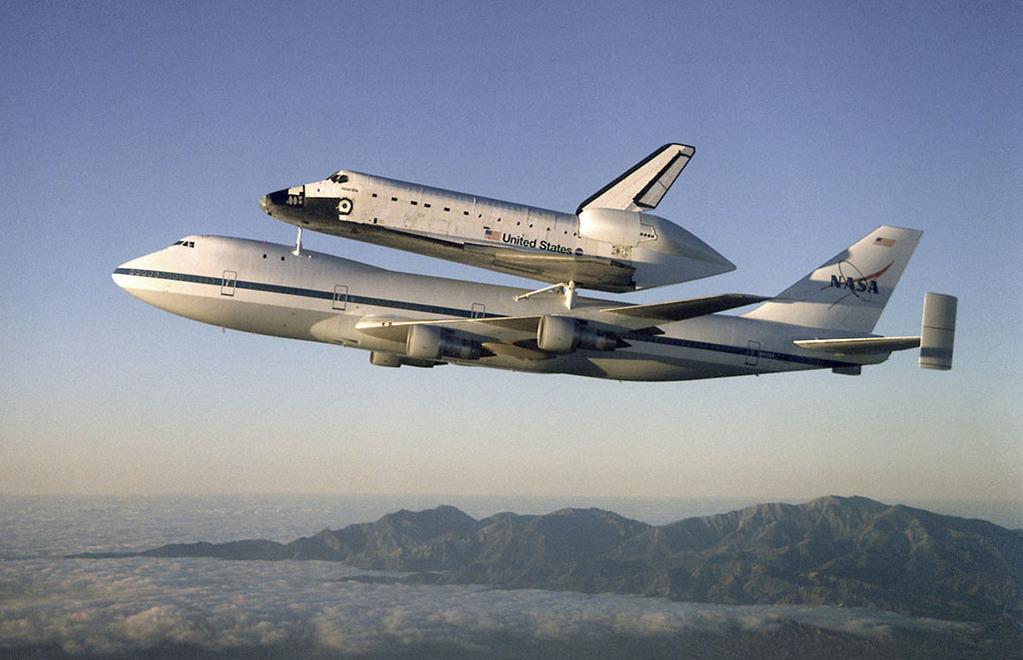

Shuttling the Shuttle

One of the more interesting facts about the space shuttle is that it essentially is a big glider. The vehicle had no real thrust capabilities of its own, relying instead on the Saturn booster system to escape Earth’s gravity. Though the shuttle could land much like a plane on a runway, it could not lift off from a runway under its own power. NASA officials faced one huge question: how do we shuttle the shuttle between the landing and take-off sites?

Wadesboro native and NASA engineer John W. Kiker had the answer. Using scaled, remote-controlled models, Kiker set about proving that the shuttle could be safely and more affordably transported by mounting it to the back of a modified Boeing 747. The NASA community was skeptical at first, but they gave Kiker the room he needed to develop the idea. Kiker’s “piggyback” plan became reality on February 18, 1977, when the shuttle Enterprise was mounted atop a 747 and carried into the sky for its first “flight.”

Two specially modified 747s, known as the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, ferried shuttle vehicles through the entirety of the program. The final piggyback flight occurred in 2012, when one of the planes carried the Endeavour from Florida to California for retirement.

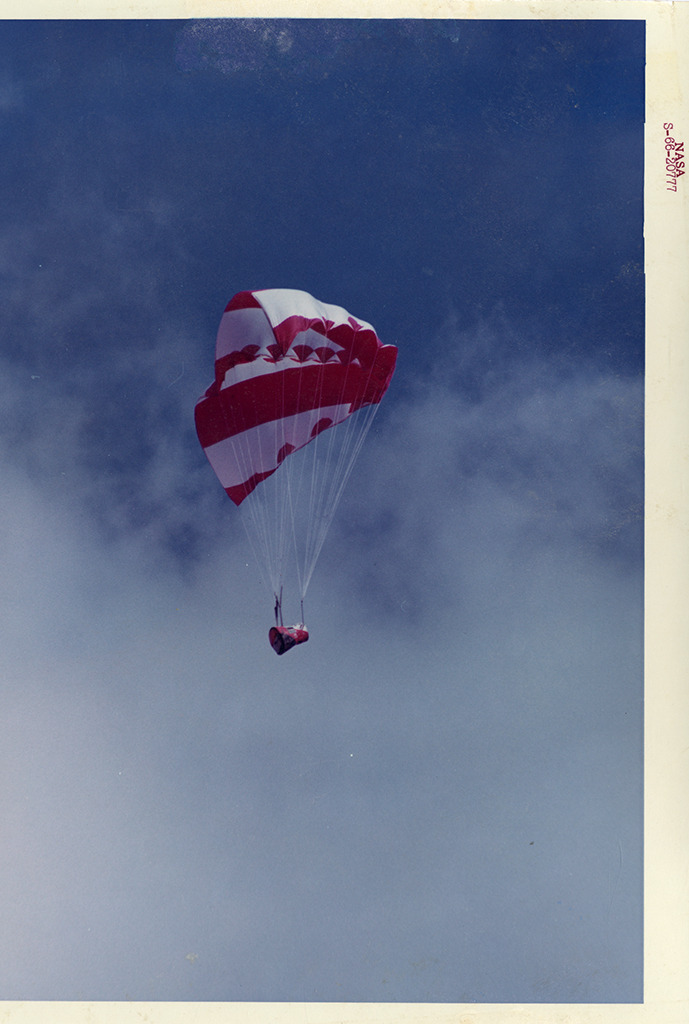

John Kiker's contributions to the American space program were not just limited to the development of the piggyback system. Early in his NASA career, Kiker and his colleagues designed the three-parachute landing system of the Apollo program. This image captures the parachute system in action during the return of the Apollo 16 crew. Courtesy NASA.

With the help of colleagues, Kiker (right) first tested his piggyback design with models. Using a 1/40th scale model of the space shuttle and a model airplane, Kiker evaluated flight control of the mated system and tested the separation of the two during a test flight in December 1975. Courtesy NASA.

Several full-scale tests of the piggyback system were conducted in 1977 at the Dryden Flight Research Center (now Armstrong Flight Research Center). Here, the shuttle Enterprise glides above its 747 carrier just moments after separation on September 13, 1977. Courtesy NASA.

Soon, piggyback flights became one of the most iconic sights of the shuttle era. Here, a 747 shuttles Atlantis back to Kennedy Space Center in 1998. NASA estimates that Kiker's design saved the government about $19 million every time a shuttle had to be transported. Courtesy NASA.

A Nation in Mourning

Beaufort native Michael J. Smith was just twenty-four when he watched Neil Armstrong take man’s first step on the Moon. Right then and there, he determined to become an astronaut. A meritorious career in the Navy followed, during which Smith learned to fly 28 different aircraft, flew 198 missions in Vietnam, and logged 4,868 hours of flight time.

In May 1980, he was accepted as an astronaut candidate and qualified as a shuttle pilot the following year. The call Smith long awaited finally came in 1985 when he was tapped to pilot the Challenger on its tenth mission. Tragically, the flight proved to be both Smith’s first and last. Just seventy-three seconds after launch on January 28, 1986, an O-ring seal in one of the Challenger’s two solid rocket boosters suffered a critical failure, leading to the disintegration of the shuttle over the Atlantic Ocean. The lives of all seven crew members were lost, including that of Mission Specialist Ronald E. McNair, a North Carolina A&T State University alumnus from South Carolina.

To date, Smith is one of twenty-four American astronauts to have lost their lives in the line of duty. In recognition of his sacrifice, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 2004.

Official NASA portrait of Beaufort native Michael Smith, taken on January 8, 1981. Courtesy NASA.

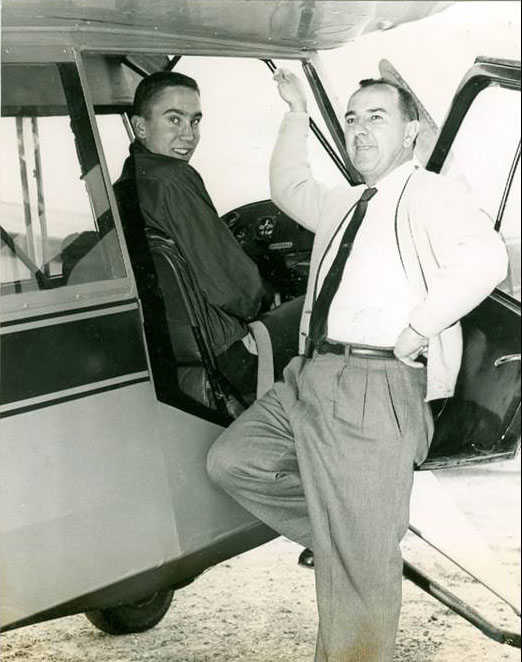

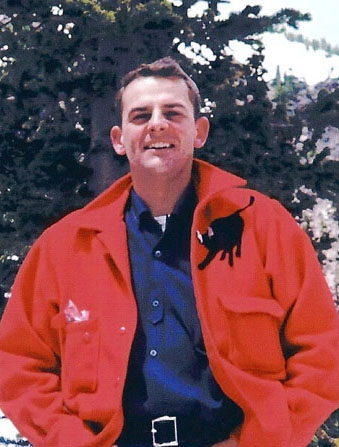

Few people pursue their dreams with a zeal and perseverance that could match Smith. At just sixteen years old, an age at which most teens are preoccupied with learning to drive, Smith took his first solo flight. He is pictured on that day in 1961 with his flight instructor Bob Burrows. Courtesy Smith Family.

On April 30, 1961, Mike Smith took his first solo flight, earning his pilot's license. In a letter to his friend Bobby, the sixteen-year-old farm boy from Beaufort could barely contain his excitement: "I went flying alright, I soloed!" Courtesy Smith Family.

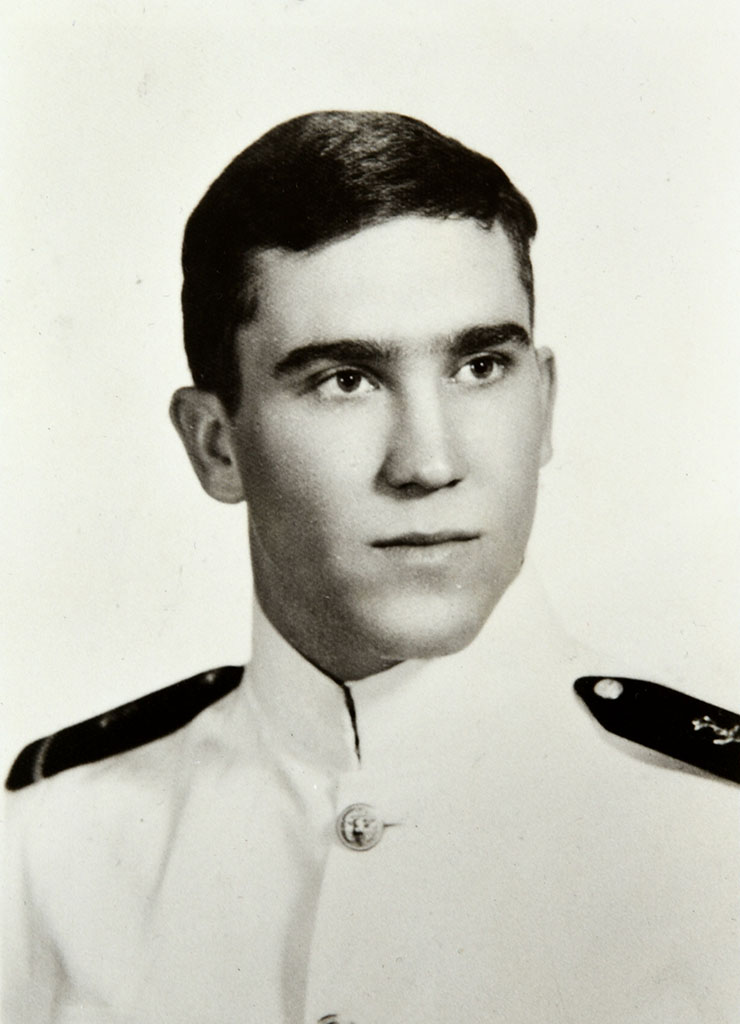

Smith entered the United States Naval Academy in 1963. He graduated four years later, ranked 108 in his class of 893. Richard Purnell, an academy classmate of Smith's, later recalled that upon meeting him, one of the first things Smith told him was "I am going to be an astronaut."

Following his graduation from the Naval Postgraduate School, Smith went on to attend flight school, earning his wings in 1969. "Whenever I was conscious of what I wanted to do," Smith once said in an interview, "I wanted to fly. I can never remember anything else I wanted to do but flying."

In 1972 and 1973, Smith served as an attack pilot assigned to the USS Kitty Hawk during the Vietnam War, flying 198 missions before returning home to attend test pilot school at the Naval Air Test Center in Maryland. He is pictured here aboard the Kitty Hawk during his wartime deployment.

NASA selected Smith as an astronaut candidate in May 1980, about the time this portrait was taken. Following a year of training, Smith qualified as a shuttle pilot. The call he long awaited finally came in 1985 when he was tapped to pilot the Challenger on its tenth mission the following year.

Mike Smith absolutely loved to fly. As quarterback of his high school football team, he once called a timeout just to watch a plane fly overhead. Here he is post-flight (left, foreground), brandishing a huge grin, in September 1985. To his right are astronauts Barbara Morgan, Christa McAuliffe, and Francis Scobee. Courtesy NASA.

The space shuttle Challenger launched for its tenth mission on January 28, 1986. Seventy-three seconds into its flight, an O-ring seal in one of the solid rocket boosters failed, resulting in the loss of the vehicle and its crew. Courtesy NASA.

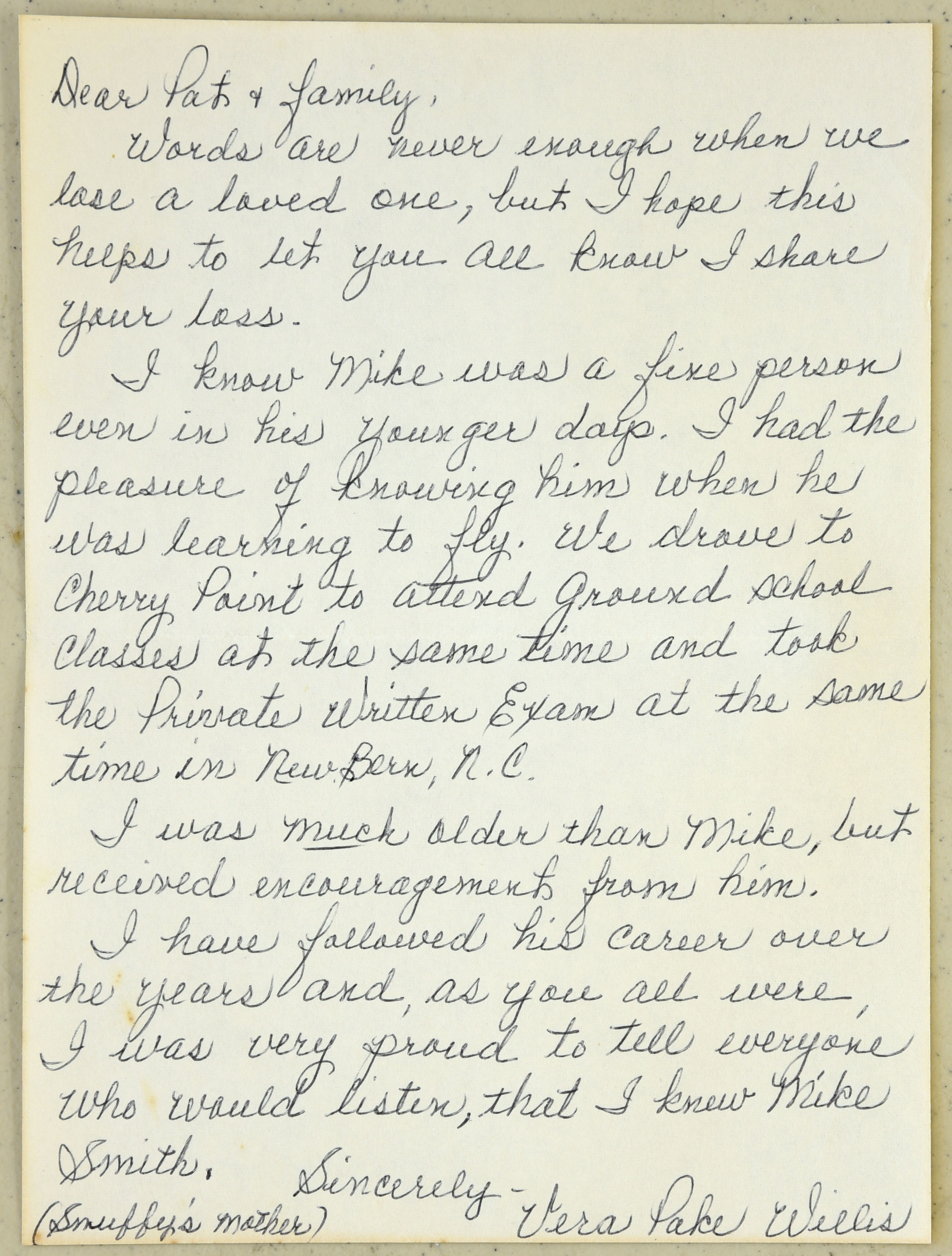

Following the accident, letters and cards poured in to Beaufort from across the nation. Sometimes the letters came from strangers, sometimes from friends and acquaintances of days gone by. One local resident wrote Mike's brother Pat to share the wonderful memories she had of knowing Mike when the two were learning to fly. Courtesy Smith Family.

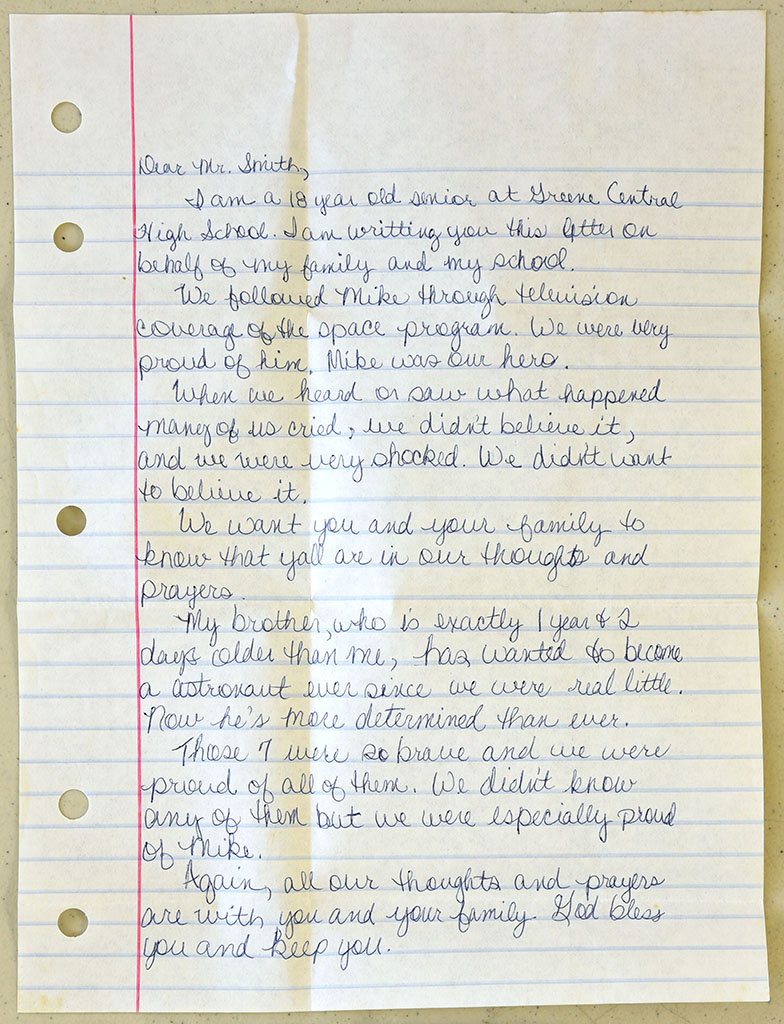

The horror of the Challenger accident played out in real time on televisions in both living rooms and classrooms, shocking not only American adults, but the nation's children as well. In the days following the accident, a high school senior named Sonya, from Hookerton, North Carolina, penned a beautiful letter to the Smith family. "My brother," she wrote, in part, "who is exactly 1 year & 2 days older than me, has wanted to become an astronaut ever since we were real little. Now he's more determined than ever." Courtesy Smith Family.

Recovery personnel retrieved the crew's official flight kit—a sixty-pound kit containing souvenirs and personal mementos—from the surface of the ocean just fifty hours after the accident. Inside that kit was this state flag, given to Mike Smith by the North Carolina Science Teachers Association. The flag's blue union has faded over the years, likely due to exposure to salt water.

Mike's wife Jane bestowed the flag to the care of Gov. James G. Martin during a ceremony on Veterans Day in 1986. In his address, Governor Martin said the flag "always brings to my mind the state motto 'Esse Quam Videri,' which translated could also have been a statement about Mike Smith—a man who exemplified this motto, 'To be rather than to seem.'" Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Smith's exemplary service during his years in the Navy, the Vietnam War, and with NASA garnered him quite a few commendations. The awards include the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the Navy Distinguished Flying Cross, the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star, thirteen Strike Flight Air Medals, three Air Medals, and the Navy Commendation Medal with “V.” Smith additionally received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, awarded posthumously in 2004 by President George Bush.

Official NASA portrait of Christina Hammock Koch, taken January 10, 2014. Courtesy NASA.

The Next Generation

Following the tragic loss of the Challenger on that fateful January day in 1986, President Ronald Reagan, in a brief but powerful address, paid homage to the crew and made a solemn promise to the American people: “The future…belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we'll continue to follow them.” And follow them we have, as North Carolinians watched with pride the preparations of one of our own to go to space.

Though born in Michigan, Christina Hammock Koch considers Jacksonville, North Carolina, her hometown. She is a proud alumna of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics and North Carolina State University, where she earned bachelor degrees in electrical engineering and physics and a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering. Koch, who was selected for astronaut training in June 2013, currently holds the record for longest continuous time in space for women. As of 2023, she remains in active service with NASA.

Since the close of the space shuttle program in 2011, NASA has had to rely upon the Russian space program to ferry American astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). North Carolinian Christina Koch (right) made the trip to the ISS alongside NASA colleague Nick Hague (left) aboard Soyuz MS-12. As is required by the Russian government, the spaceflight was commanded by cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin (center). Courtesy NASA.

The second half of the Expedition 59 crew launched for the International Space Station on March 14, 2019. They are pictured here in front of their Soyuz MS-12 spacecraft during pre-launch activities in February 2019. From left to right: Christina Koch, of North Carolina; Alexey Ovchinin, of Russia; and Nick Hague, of Kansas. Courtesy NASA.

American passengers of the Soyuz spacecraft wear Sokol spacesuits, modern-day variants of a design that debuted during the era of the Soviet Union. Taken the day of the launch, this photo shows Koch going through pre-flight checks and preparations in her Sokol suit at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Courtesy NASA.

Soyuz MS-12, carrying Christina Koch, Nick Hague, and Alexey Ovchinin, launched on March 14, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

Christina Koch (center) helps fellow astronauts Nick Hague (left) and Anne McClain (right) prepare for their first spacewalk on March 22, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

Koch, pictured here outside the ISS, made her first spacewalk on March 29, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

Project Apollo

Project Apollo

American astronaut Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin became the second man to step foot on the Moon on July 21, 1969. Courtesy NASA.

Project Apollo’s ultimate goal—to put a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth—was achieved just eight years after President John F. Kennedy’s challenge, a testament to American ingenuity and perseverance.

Between 1969 and 1972, twelve men walked on the Moon. This feat, however, could not have been achieved without the support of hundreds of thousands of Americans from a wide range of professions. North Carolina engineers, mathematicians, manufacturers, scientists, and aviators all contributed greatly to the successes of Project Apollo.

North Carolina State Contracts

Medicine, mission patches, and special alloys—the contributions of North Carolina manufacturers, though limited in number, cannot be overlooked. From 1961 to 1972, when the final Apollo mission was flown, NASA awarded state-based contractors more than $23,000,000 in contracts.

This Apollo 16 mission patch was made by Buncombe County-based A-B Emblem. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

North Carolina-based Burroughs Wellcome provided several key medicines for Apollo missions, including Neosporin (an antibiotic ointment), Marezine (for motion sickness), and Actifed (for sinus/ nasal congestion). Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Monroe-based Allvac Metals Company used turbines like this one to produce Renee 41, a special alloy used in the production of the heatshields for Gemini and Apollo spacecraft. The heatshield protected the astronauts from the intense heat created by the spacecrafts' re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

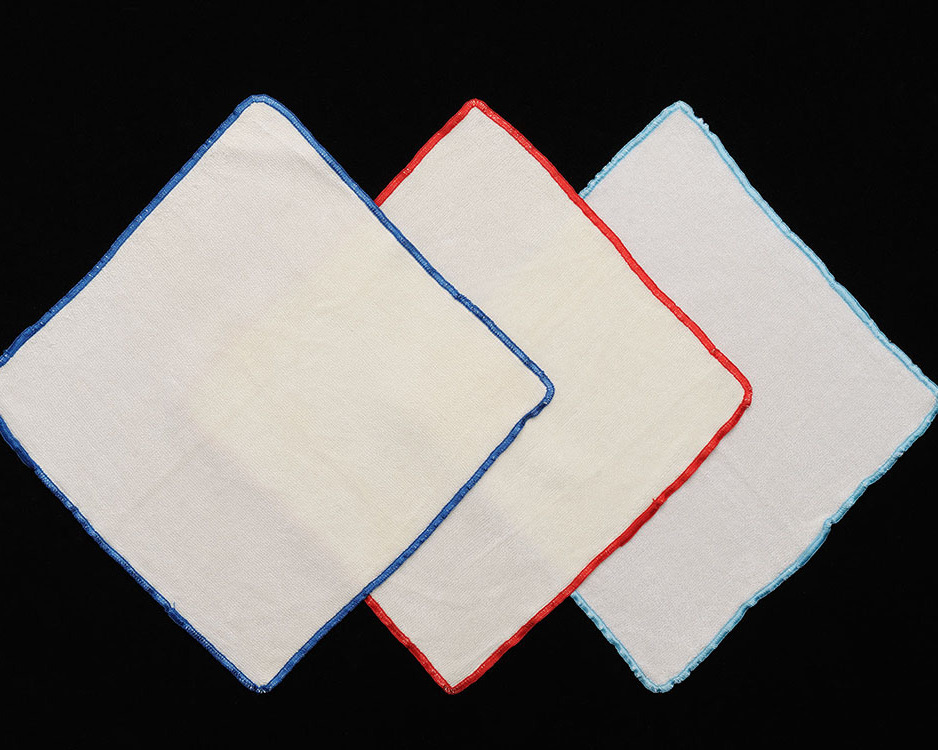

Lightweight, compact washcloths made by the School of Textiles at North Carolina State University accompanied astronauts on Gemini and Apollo missions. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Corning Glass produced several key components for American spacecraft, including the window glass through which astronauts caught their first glimpses of the Moon and the Earth from space. Here in North Carolina, specifically Raleigh, Corning facilities manufactured glass capacitors and memory banks used in Apollo-era spacecraft. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Batteries made by Exide Missile powered pyrotechnic systems in the command, service, and lunar modules. Parachute deployment, mid-course maneuvers, ascent and descent of the lunar lander—just a few of the processes powered by batteries made in Raleigh. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

From Apollo 13 up to the present, A-B Emblem, a company based in Weaverville (Buncombe County), has been the sole provider of official NASA mission patches. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

As head of the computing unit at Muroc, Person County native Roxanah Yancey supported Chuck Yeager's sound-barrier-breaking 1947 flight by, according to NASA, "identifying traces on film, marking time to coordinate all data recordings and reading film deflections before converting them into engineering units." She went on to become an aerospace engineer and studied the effects of speeds Mach 6 and greater on aircraft. Courtesy NASA.

Human Computers

In the early days of NASA, people—not devices that provided instant results—performed the mathematical calculations necessary to put a man in space. Women, including some from North Carolina, comprised the majority of these “calculators,” or “computers,” taking on work originally performed by engineers. Their tools of the trade were not electronic, or even necessarily electric; they were likely hand-manipulated slide rules, spring-loaded calculating machines, pencils, and paper.

By the time of Apollo, the arrival of computing machines—the beginnings of today’s computers—had revolutionized their work, and many women transitioned into computer programming.

Mary Hedgepeth (standing, far left), of Cleveland County, and Roxanah Yancey (standing, third from left), of Person County, both worked as computers for NASA’s precursor—the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or NACA—at Muroc Air Force Base in California. They are pictured here with fellow computers in 1949. Courtesy NASA.

North Carolina natives Roxanah Yancey, center, and Mary Hedgepeth, far left, computed data in support of high speed flight studies for the NACA Muroc Flight Test unit. Courtesy NASA.

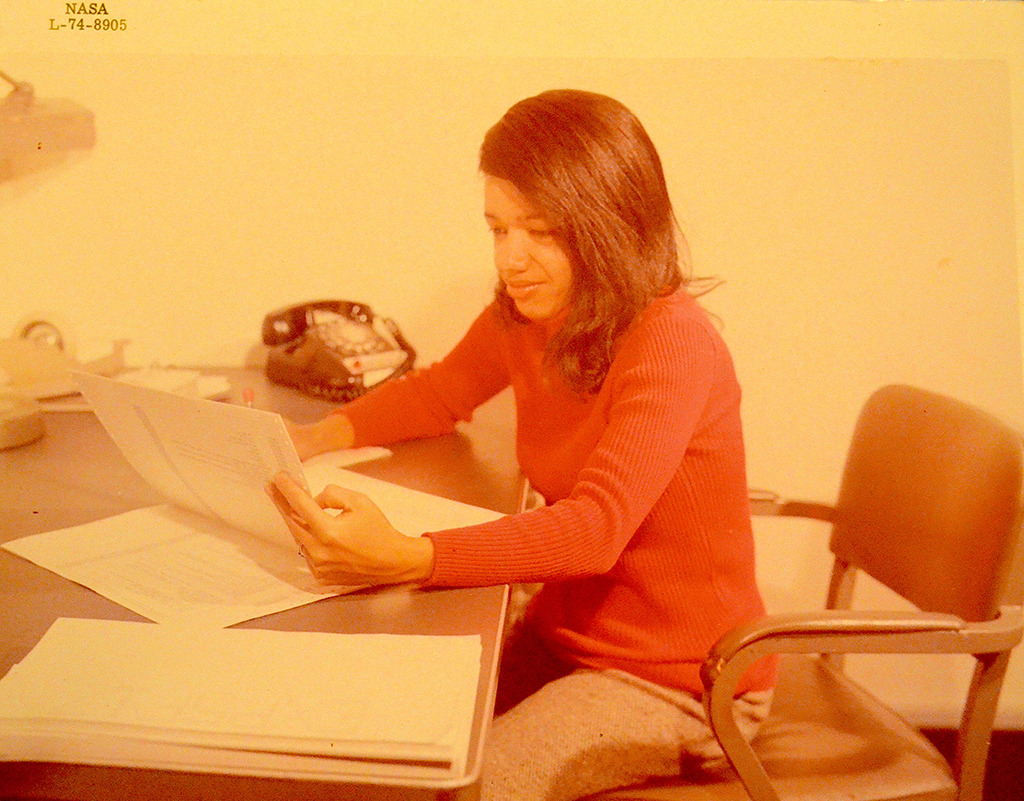

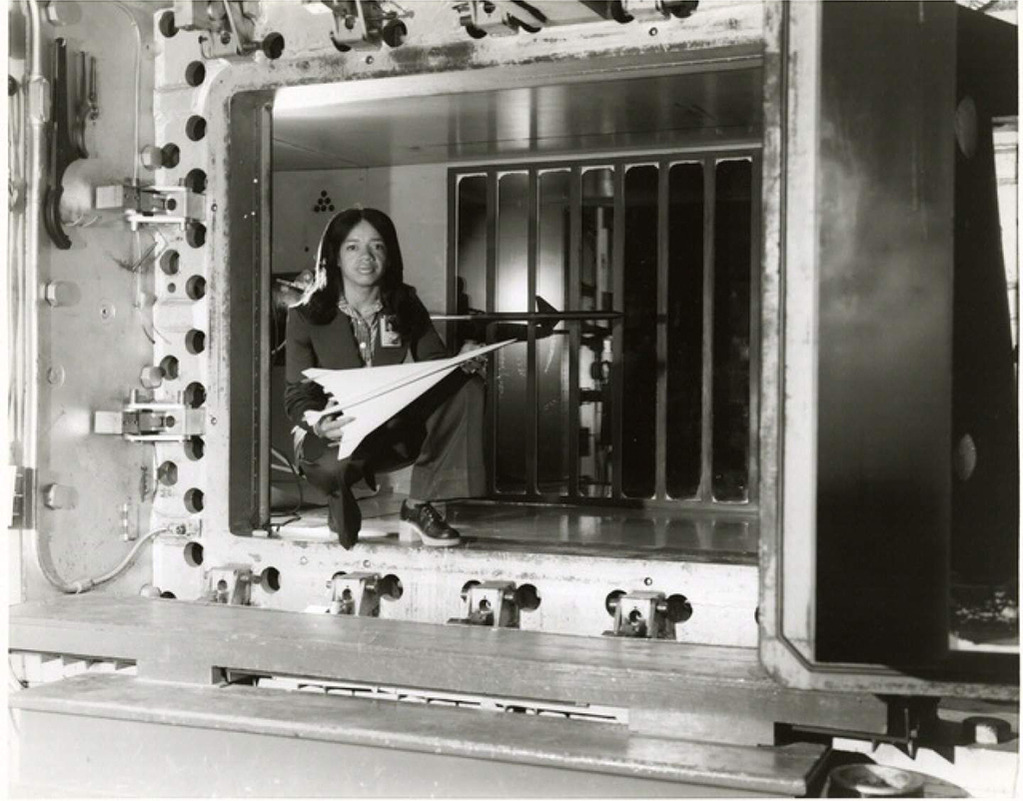

Monroe (Union County) native Dr. Christine Darden—shown here at Langley Research Center in 1974—began her NASA career as a computer in 1967. Soon after her arrival, she and her colleagues transitioned into computer programming and wrote programs that could perform the necessary calculations. Courtesy Dr. Christine Darden.

In 1972, Dr. Christine Darden transferred to an engineering section that was charged with minimizing sonic booms. For 20 years, she specialized in this research, moving us closer to a more commercially friendly, low-boom aircraft design. Dr. Darden concluded a distinguished forty-year career with NASA in 2007 and is recognized today as one of the world’s foremost experts on supersonic wing design and sonic boom mitigation. Courtesy National Air and Space Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

The short film above, appearing here courtesy of Scholastic, explores the life and career of Union County native Christine Darden. Dr. Darden's NASA career—from data analyst to aeronautical engineer—was profiled in the book Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, by Margot Lee Shetterly.

An Army of Contractors

Not everyone who supported NASA’s efforts to go to the Moon worked for the agency directly. Companies representing a variety of fields from all around the country entered into contracts with the federal government to supply NASA with specialized knowledge and technology. At the height of the space race, the number of contracted employees reached into the hundreds of thousands. It remains a mystery just how many North Carolinians helped put a man on the Moon without ever brandishing the NASA logo.

In 1966, Arthur B. "Art" Case, who later retired to North Carolina, was considered to be one of the “five…most important IBMers” at Cape Kennedy in Florida. From the relative safety of the blockhouse, Case and his fellow IBM test conductors were responsible for the final checks of the launch control equipment in preparation for vehicle liftoff. It was a high-pressure, high-stakes job, an environment in which Case seemed to thrive. As manager of Complex 34 during the Saturn IB program, Case witnessed firsthand both the tragedies and triumphs of the American space program.

North Carolinian Arthur Case supported America's race to space as a contractor from IBM. Courtesy Steve Case.

Art Case was on-site when the Apollo 204 (later renamed Apollo 1) fire broke out. Former colleagues remember how he immediately flew into action, running through a series of switches and panels to shut down systems faster than it had ever been done before. Courtesy Steve Case.

Art Case, standing right, assists a colleague at Kennedy Space Center's Complex 34. Courtesy Steve Case.

Case's first major triumph came on February 26, 1966, with the successful launch of Apollo 201, for which he served as chief test conductor. The primary goals of the unmanned, suborbital flight were to test both the Saturn 1B launch vehicle and the heat shield of the spacecraft. Courtesy NASA.

Art Case, far right, was a manager with IBM at Kennedy Space Center during the Apollo program. Courtesy Steve Case.

Following the successful flight of Apollo 7, several IBM team members celebrated at a local bar. The establishment had the strange custom of cutting off the neckties of their patrons. The severed ties were all collected, arranged to spell "Apollo 7," framed, and awarded to Art Case for his leadership during the mission. Courtesy Steve Case.

As the space race wound down following the success of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, IBM began reassigning employees to other stations around the country. Such a reassignment brought Art Case (center) to North Carolina. Courtesy Steve Case.

Charlotte-born Charles Duke became the youngest person to walk on the Moon on April 21, 1972. Courtesy NASA.

Charles Duke and Apollo 16

Charles M. “Charlie” Duke is the only man with North Carolina ties to have walked on the Moon. Though born in Charlotte, Duke was raised across the state line in his parents’ home state of South Carolina. He went on to graduate from the United States Naval Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1966, at the age of thirty, Duke was one of nineteen men selected for Astronaut Group 5.

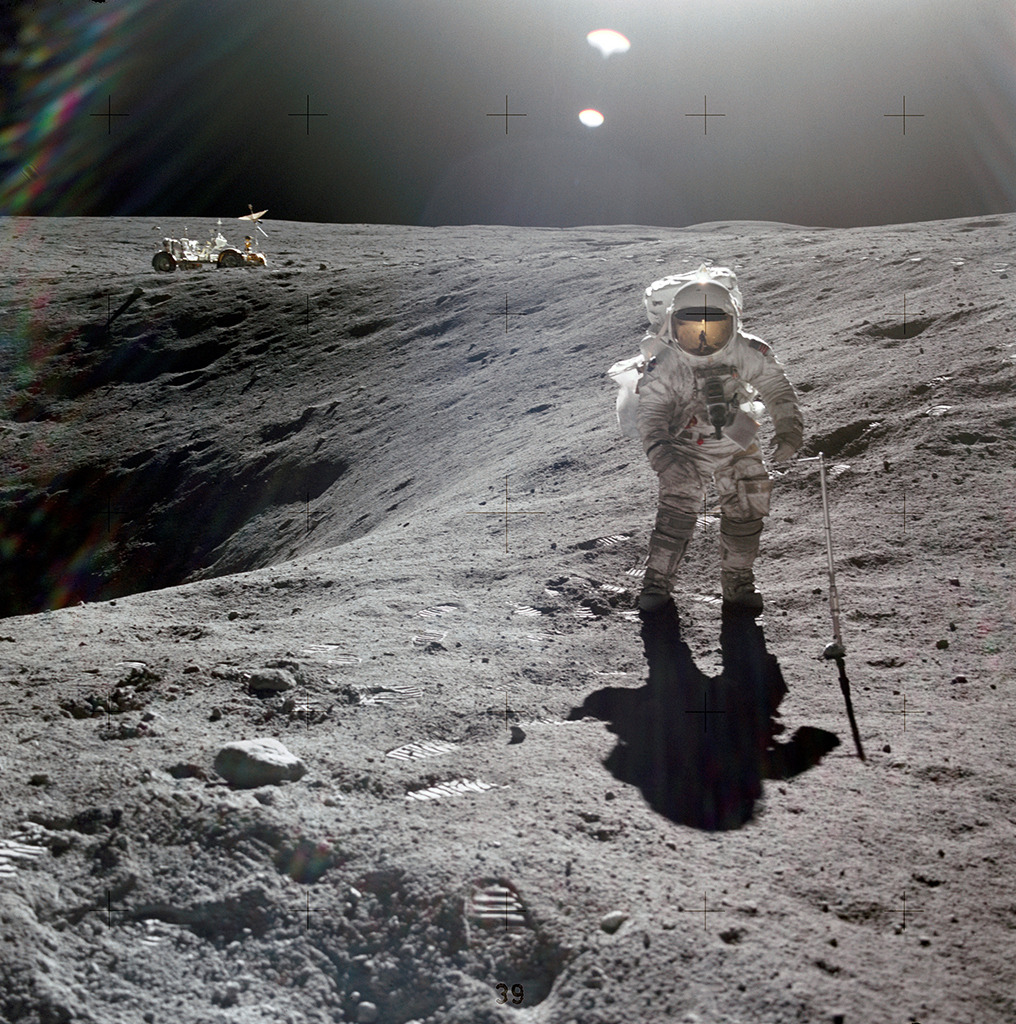

In 1972, Duke served as the lunar module pilot for the Apollo 16 flight. Mission commander John Young accompanied Duke to the lunar surface. Together, Duke and Young collected samples and conducted a series of experiments in the Descartes Highlands, a crater-pocked region on the near side of the Moon, from April 21 through 23, 1972. The team remained on the lunar surface for seventy-one hours.

Duke served as a member of the astronaut support crew for Apollo 10 and as CAPCOM—the main point of contact between spacecraft crew and mission control—for Apollo 11. Courtesy NASA.

Some training for the Apollo 16 flight occurred on the property of Kennedy Space Center. Here, Duke practices deploying a core tube with a hammer in March 1972. Courtesy NASA.

Duke became the youngest person to walk on the Moon on April 21, 1972. Courtesy NASA.

During their seventy-one hours on the Moon, Duke and fellow astronaut John W. Young collected samples and conducted a series of experiments in the Descartes Highlands, a crater-pocked region on the near side of the Moon. Courtesy NASA.

Geological Investigation

Due to a medical condition, UNC Chapel Hill alumnus and professor Dr. Joel S. Watkins was declared medically ineligible for NASA’s scientist-astronaut program—the same program that put fellow geologist Harrison Schmitt on the Moon. Undeterred, Dr. Watkins sought alternative means of supporting geological and geophysical study of the lunar subsurface.

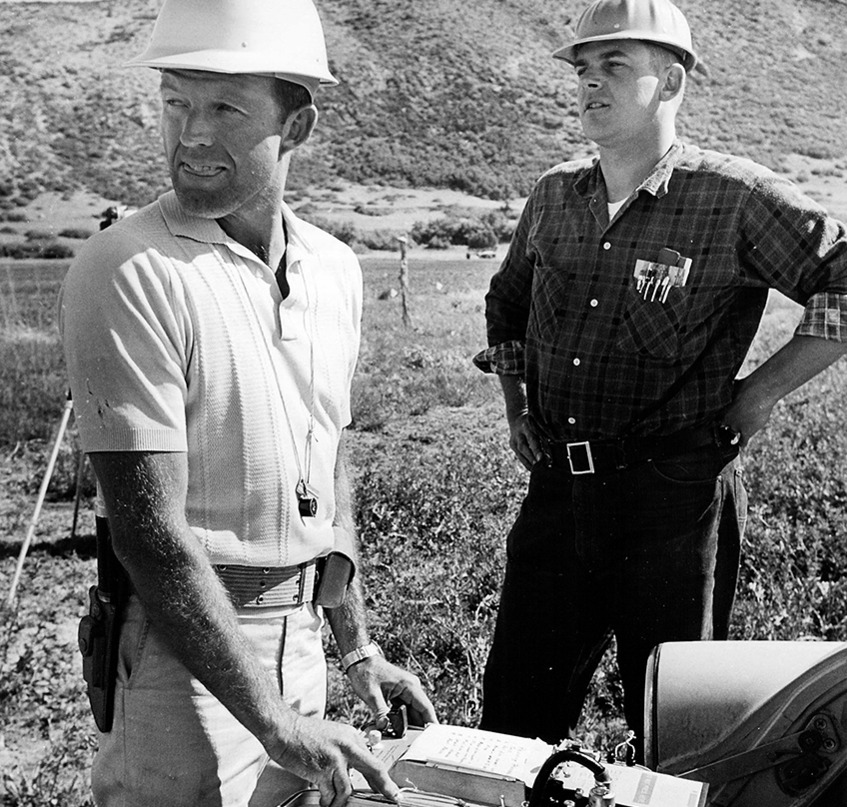

In June 1964, Dr. Watkins and colleagues from the Astrogeology Branch of the US Geological Survey conducted a geological field school at the Philmont Scout Ranch in northern New Mexico. There, they trained Apollo astronauts in geologic mapping, field note documentation, and how to analyze subsurface structure using magnetometers, seismometers, and gravimeters.

And though he could not make the trip through space himself, Dr. Watkins found another way to contribute to man’s investigation of the Moon’s physical makeup. During Apollos 14, 16, and 17, astronauts deployed devices developed by Watkins to measure moonquakes. The results of those experiments are still being analyzed today, to deepen our understanding of the Moon’s composition.

Geologist Joel S. Watkins devised several means of seismographic investigation of the Moon's composition for Apollo-era astronaut crews. Courtesy Catherine Barker.

Dr. Watkins observes astronaut Gordon Cooper's operation of a piece of equipment during the June 1964 geological field school at the Philmont Scout Ranch. Courtesy NASA.

Dr. Watkins, right, discusses gravity meter data with astronauts (from left to right) David Scott, Neil Armstrong, and Roger Chaffee in June 1964. During the course of the field school, Dr. Watkins built up quite a rapport with the astronauts. On the last night of the school, he and fellow USGS colleague Norman "Red" Bailey short-sheeted several of the astronauts' beds before going to sleep. Courtesy NASA.

Astronauts Alan Shepard, right, and Edgar Mitchell, left, practice using a piece of seismographic equipment known as a "thumper" that was designed by Dr. Watkins. Courtesy NASA.

In a photograph taken from the Modularized Equipment Transporter, astronauts Edgar Mitchell (foreground, left) and Alan Shepard can be seen deploying seismographic equipment developed by Dr. Watkins on the lunar surface during the Apollo 14 mission. Courtesy NASA.

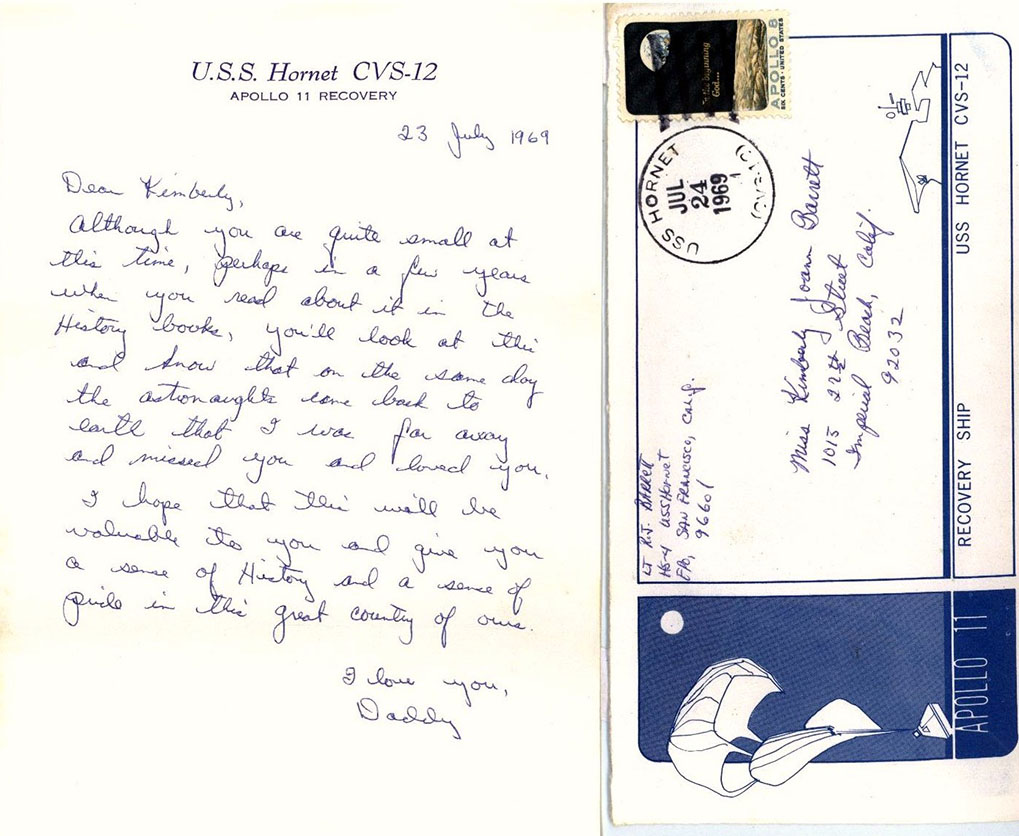

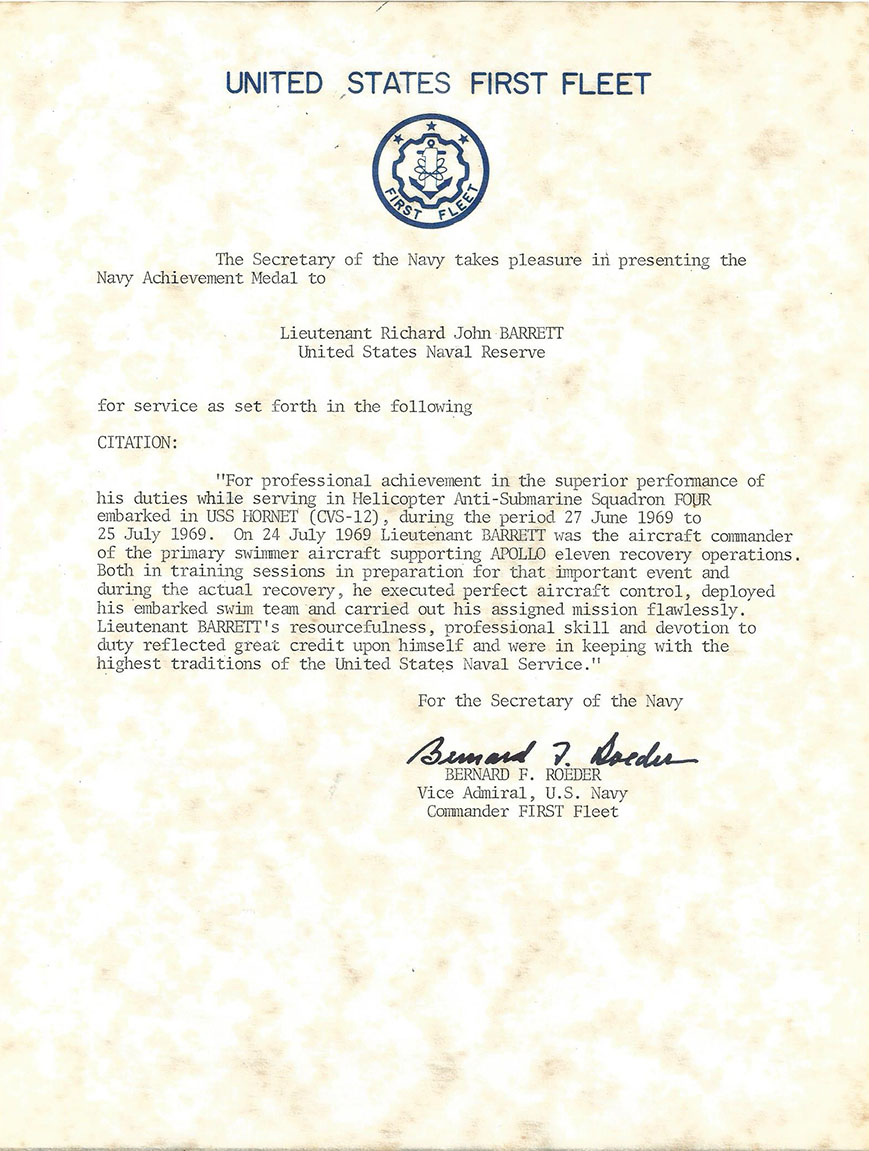

Philadelphia-born Richard J. Barrett moved to North Carolina as a toddler, spending his childhood years in Canton (Haywood County) and Asheville (Buncombe County). Following graduation from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he entered active service with the US Navy and completed a tour of the Gulf of Tonkin during the Vietnam War. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Astronaut Recovery

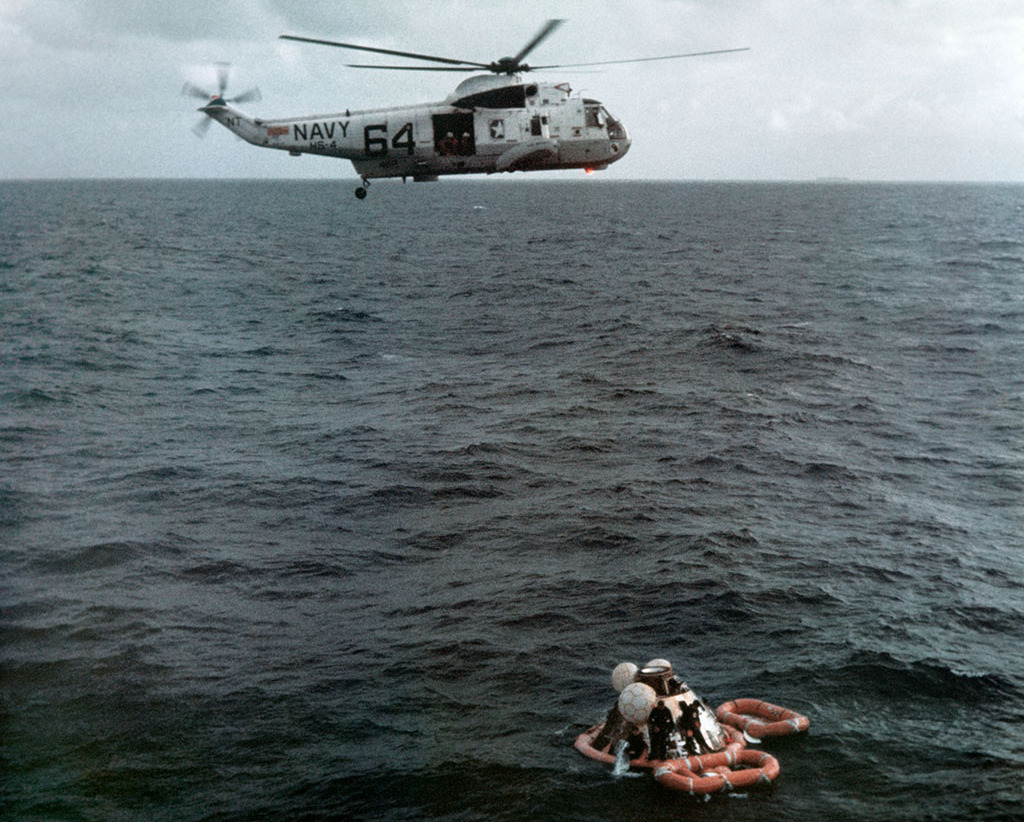

After Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7" capsule sank—and he nearly drowned—during the second manned Mercury mission, NASA worked closely with military partners to overhaul recovery protocol. As a member of Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Four (HSC-4), Lt. Richard J. Barrett—who grew up in Asheville and Canton—contributed to the development of search and rescue procedures for early manned Apollo flights.

Though he participated in the recoveries of Apollos 8 and 10, it was his involvement in helping to develop and execute search and rescue procedures for Apollo 11 that is perhaps most firmly etched in his mind. Piloting helicopter 64 that July day in 1969, Lieutenant Barrett skillfully and expertly dropped Navy swimmers and important gear next to the bobbing Apollo 11 capsule.

As pilot of helicopter 64, Lieutenant Barrett was responsible for transporting a Navy swim team to the splashdown site of the Apollo 11 capsule. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Lieutenant Barrett stayed on-scene as the swimmers attached a flotation collar to the capsule, inflated rafts, and helped the astronaut crew into contamination suits. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

With the Apollo 11 recovery mission looming just one day out, Lieutenant Barrett sat down and penned a sweet, short letter to his then two-month-old daughter Kimberly. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Lieutenant Barrett's Navy Achievement Medal reads, in part, "Both in training sessions…and during the actual recovery, he executed perfect aircraft control, deployed his embarked swim team and carried out his assigned mission flawlessly. Lieutenant Barrett's resourcefulness, professional skill and devotion to duty reflected great credit upon himself and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service." Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

For his service during the Apollo 11 recovery, Lieutenant Barrett received a Navy Achievement Medal and this accompanying certificate. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Project Gemini

Project Gemini

A highlight of the Gemini program was the successful space walk of astronaut Edward H. White II on June 3, 1965. Courtesy NASA.

NASA’s second phase of space exploration was called Project Gemini. Gemini’s ten manned missions flew in 1965 and 1966, successfully demonstrating man’s ability to live and work in space for extended periods of time.

Primary aspects of the Gemini program included the implementation of spacecraft built for teams of two astronauts, the development of safer reentry and splashdown procedures, the introduction of maneuverability options to spacecraft, and the advent of “extravehicular activities,” or walking in space.

Upon Gemini’s completion, astronauts and support staff were well prepared for the grueling six- to twelve-day missions of the Apollo program.

Rogallo Wing

In the early stages of Gemini, NASA engineers developed an alternative to the parachute landing “splashdown” method that had been used with Mercury spacecraft. One of their options was a kite-like parawing, the creation of long-time Outer Banks residents Francis and Gertrude Rogallo.

The Rogallos’ parawing would have allowed astronauts to steer the Gemini capsule back to Earth’s surface and land it much like any other aircraft. Testing proved the concept, but engineers ultimately opted to retain the parachute landing system. While the Rogallos had missed an opportunity for space fame, their flexible-wing technology revolutionized the sport of hang gliding and remains in use to this day.

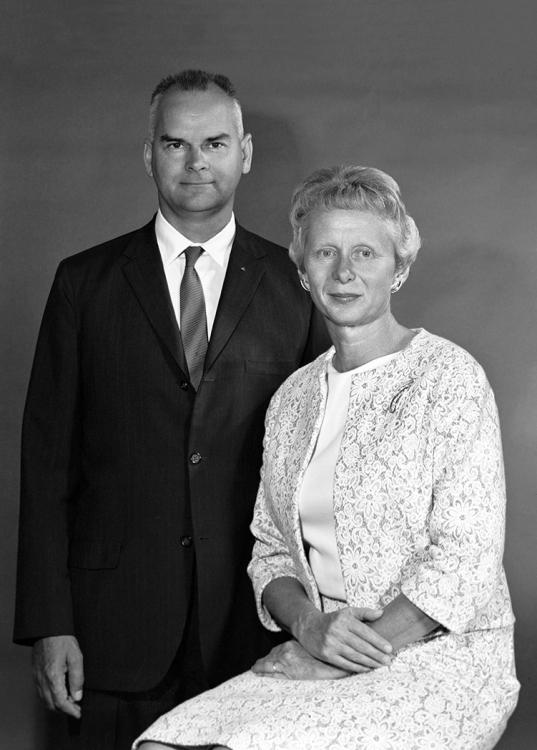

Long-time Outer Banks residents Francis and Gertrude Rogallo patented their wing design in 1951. Courtesy NASA.

Development of the Rogallos' parawing, or paraglider, concept for application during the Gemini program received authorization in 1961. This photograph, taken during a drop test, shows the deployed paraglider with a Gemini boilerplate, or practice, capsule. Courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

The primary goal of the parawing was to provide astronauts with a controllable landing system. As shown in this illustration by Paul Meltzer, the parawing would have allowed astronauts to make a controlled descent in order to land the capsule on land. Though testing proved the concept was reliable, several factors, including waning funding and intellectual support, prevented the wing's integration into the Gemini and Apollo programs. Courtesy National Geographic Image Collection.

As a NASA engineer, Francis Rogallo lobbied for the wing to replace the parachute landing system used during Project Mercury. NASA pursued the idea during the developmental years of the Gemini program. Here, a NASA technician assists in the testing of the Rogallos' design in 1965 at the Langley Research Center in Virginia. Courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

Aerial view of the tracking station's campus around 1981, when the facility was transferred to the Department of Defense. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

Rosman Tracking Station

In 1963, NASA opened a Satellite Tracking and Data Acquisition facility on the edge of Pisgah National Forest near Rosman (Transylvania County). The chosen site exhibited several important qualities: it was government-owned, had an absence of light pollution, and was free of electromagnetic interference.

The base at Rosman, one of twenty-three located around the world, served as the primary east-coast tracking station for satellites and manned spacecraft. The base consisted of two dish-shaped antennas—one measuring an astonishing eighty-five feet wide—that sent and received commands, scientific data, and location information.

Photograph of the construction of the eighty-five-foot-wide dish, or ear, that "listened" for signals from manned and unmanned spacecraft at Rosman. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

View of construction underway on the tracking station in Rosman, around 1963. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

Agena Launch Director

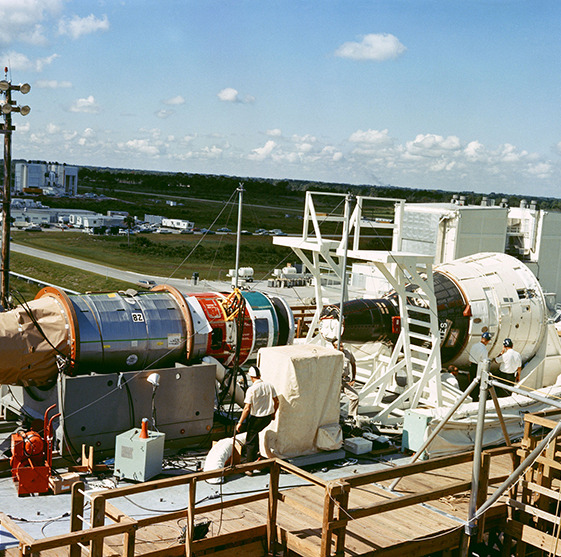

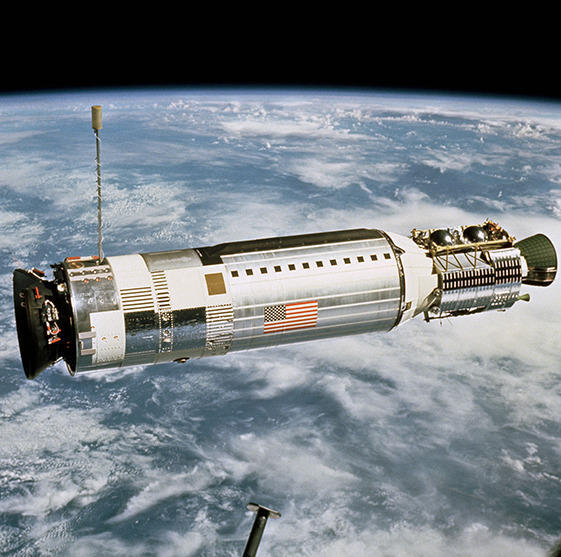

A key goal of the Gemini program was to successfully dock a crew capsule with another spacecraft while in orbit, a skill that would have to be tested and perfected before the space program could take on the Apollo missions. Gemini astronauts practiced the maneuver using an unmanned spacecraft called the Agena Target Vehicle. The two vehicles required separate, but perfectly timed, launches from Cape Canaveral. Any minor delay on the ground impacted the ability of the two crafts to rendezvous in space.

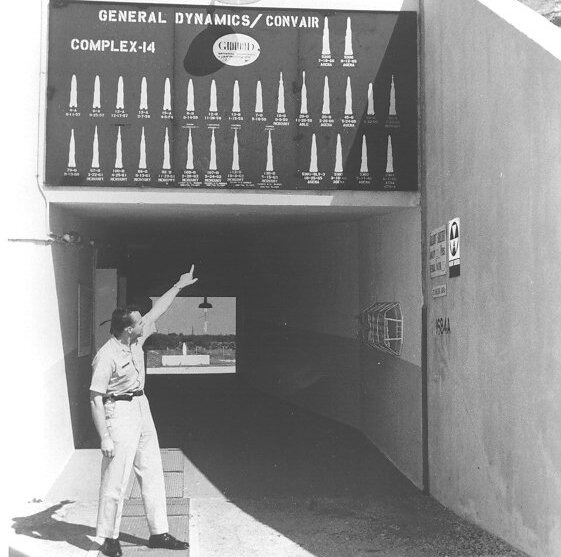

The high-stress environment didn’t deter Lt. Col. LeDewey “Jack” Allen of the Air Force’s 6555th Aerospace Test Wing. From 1963 to 1967, the Alamance County native served as commander of the SLV-3 Division, an assignment that also made him the launch director for seven Agena Target Vehicle launches in 1965 and 1966. Working in tandem with colleague and Gemini launch director Lt. Col. John G. Albert, Allen was responsible for running final checks on the Agena and its Atlas booster before giving the “go, no-go” status to NASA’s deputy director of launch operations.

From Launch Complex 14, Lt. Col. Allen was responsible for overseeing the launch status of the Agena Target Vehicle, or ATV. The ATV was launched into orbit by an Atlas rocket, as shown here. This ATV was launched on March 16, 1966, for the Gemini 8 flight. Courtesy NASA.

NASA officials conducted a docking exercise of the cylindrical Agena Target Vehicle, left, and the Gemini 6 space capsule, right, at the Boresite Range Tower in August 1965. Courtesy NASA.

The ATV in orbit is shown here in November 1966. The photograph was taken from the Gemini 12 spacecraft from about fifty feet away. Courtesy NASA.

A view of some of the infrastructure of Launch Complex 14, from which the Agena Target Vehicle was launched. The unidentified man is pointing to a visual representation of all the successful launches from the complex. From Mark C. Cleary, The 6555th: Missile and Space Launches Through 1970, 45th Space Wing History Office.

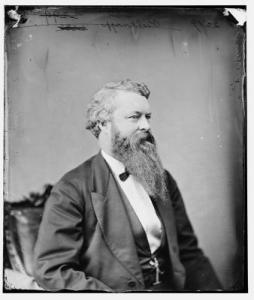

Reflections of the Kirk-Holden War

Reflections on the Kirk-Holden War

In the time since Governor William Woods Holden's impeachment, many historians have argued that his crusade against the Ku Klux Klan was a failure. Politically speaking, it was. The arrest of Josiah Turner, Jr.—whether ordered by Holden personally or not—turned the tide of public opinion decidedly away from the Republicans, resulting in Conservative dominance in the August 1870 election. The new Conservative majority in the legislature wasted no time in exercising the immense powers handed them by voters, removing Holden from office and forever ending his political career. Early Reconstruction gains, so recently won and tenuously preserved, faltered under the strain of the backlash. By the end of the whole affair, the dream of an interracial democracy in North Carolina lay in serious doubt.

Despite the political costs, however, when examining the effectiveness of Governor Holden's anti-Klan operation itself, the evidence shows that it was moderately successful. Klan activity in Caswell and Alamance counties, and in the greater Piedmont region generally, decreased significantly. Colonel George W. Kirk's men arrested around 100 suspected Klan members for committing crimes such as murder and other violent acts of intimidation.

Contrary to Conservative reports, Kirk's forces had accomplished this feat without a single life lost on either side of the fray. The majority of Kirk's prisoners testified that they had received fair treatment. And though Holden had been officially barred from holding office in North Carolina, he remained a significant influence in Republican Party politics in the state capital up through the early 1880s.

As Holden's life neared its end, the desire to clear his record on the Klan affair grew. Many friends put forth requests for a pardon for Holden from the legislature, but when the issue was threatened with a floor debate, Holden withdrew the request as he did not wish to agitate those who had closed that chapter. In his waning years, Holden appealed to the legislature, requesting a restoration of his political rights. Holden argued that what he did during the anti-Klan campaign he did with the "best and highest interests of the State." He closed the widely-published card passionately affirming to be true what many state citizens had long doubted:

"I am not a party man. Both parties have disowned me. I appeal to you solely on the ground of justice. I have never been an enemy to the State. On the contrary, I have loved her well, and do now, and am her loyal son, though proscribed and banned."

Photograph of Governor William W. Holden. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

Additional Readings on the Kirk-Holden War and Reconstruction

Bradley, Mark L. Bluecoats & Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction North Carolina. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Brisson, Jim D. "'Civil Government Was Crumbling Around Me': The Kirk-Holden War of 1870." The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 2 (2011): 123–63.

Folk, Edgar E. and Bynum Shaw. W. W. Holden: A Political Biography. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1982.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988.

Harris, William C. "W.W. Holden: In Search of Vindication." The North Carolina Historical Review 59, no. 4 (1982): 370-1.

Harris, William C. William Woods Holden: Firebrand of North Carolina Politics. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Holden, William Woods. Governors' Papers. State Archives of North Carolina.

McGuire, Samuel B. "'Rally Union Men in Defence of your State!': Appalachian Militiamen in the Kirk-Holden War, 1870." Appalachian Journal 39, no. 3/4 (2012): 294–323.

Raper, Horace W. William W. Holden: North Carolina's Political Enigma. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 1985.

Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy And Southern Reconstruction. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

Troxler, Carole Watterson. "'To Look More Closely at the Man': Wyatt Outlaw, a Nexus of National, Local, and Personal History." The North Carolina Historical Review 77, no. 4 (2000): 403–33.

Walder, Christopher. "Civil War and Reconstruction." In A History in Documents: Lynching in America, 95–114. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

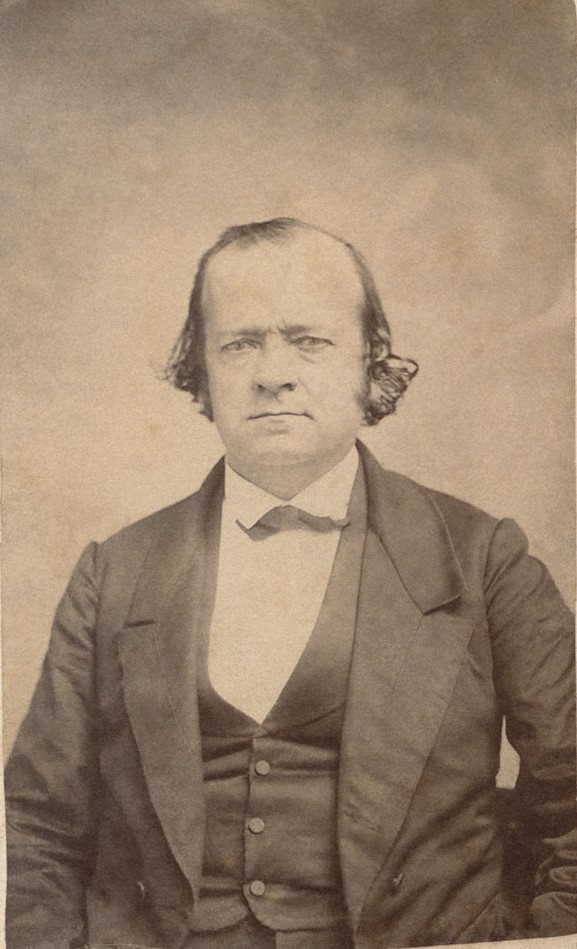

Guilty as Charged

Guilty as Charged

The Ku Klux Klan wasn't the only enemy Governor William Woods Holden had to fight. Conservative newspapers, in particular The Daily Sentinel edited by former Whig politician Josiah Turner Jr., exaggerated or fabricated stories about alleged outrages committed by Holden's soldiers. In one such story, Turner's Sentinel accused Colonel George B. Bergen of repeatedly hanging a man named William B. Patton to coerce a confession of Klan affiliations. Though Patton did confess to being a Klan member, he later denied the allegation of being tortured by Bergen.

In addition to the media, Governor Holden had to deal with an occasional lack of discipline from his own militia. In one such case in July of 1870, one of Colonel George W. Kirk's lieutenants was patrolling past the Mansion House hotel in Salisbury when his pistol accidentally discharged. Confused by the sudden gunfire, the men under his command opened fire on the hotel and pointed their weapons at patrons who were just eating breakfast. No one was injured, but the episode, alongside the propaganda war waged by Conservative press, began to incite public animus for Holden's anti-Klan campaign.

However, the arrest of Josiah Turner by Holden's men served to turn the governor's allies, and the state, against him. Some debate about who was ultimately responsible for the decision to arrest Turner remains to this day. Though Holden's contemporaneous critics placed the blame squarely on him, Holden staunchly denied it, accusing Colonel Bergen of having gone rogue in the act. And there is some evidence to support this assertion. In a November 1870 letter addressed to Holden, Militia general Richard T. Berry recounted a conversation he had with Bergen shortly after Turner's apprehension:

Soon after my arrival that afternoon at the Co. [Company] Shops I went to see Bergin and asked him if you ordered the arrest of Turner. His reply was [']By God No I did it myself. I knew Holden wanted it done, and didn't have the nerve to say so. So I ordered Lt. Hunnycut & several men to go and do it...['].

Regardless of the order's origination, Turner's arrest marked a turning point for Governor Holden's relationship with the Federal government, as court and government officials began to lose faith in his tactics. A Federal judge issued writs of habeas corpus in early August and ordered the more than 100 alleged Klan members that had been arrested by Kirk's men turned over to the courts. Governor Holden appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant to rescind the writs, but Grant declined.

Releasing the suspected Klan members to the civilian court system largely marked the end of Holden's anti-Klan campaign, but Conservative backlash continued. In a shocking upset, Conservative candidates swept the election held in August, assuming the majority in the General Assembly. The new Conservative majority wasted no time in introducing articles of impeachment against Holden, which, in part, accused him of attempting to "stir up a civil war."

In total, eight articles of impeachment passed the state house of representatives. The articles charged Governor Holden with illegally declaring the counties of Alamance and Caswell to be in states of insurrection; the unlawful apprehension of 102 men, including Josiah Turner Jr.; the suspension of habeas corpus and refusing the accused proper trials; and the improper use of state funds in the recruitment and compensation of Kirk's militia.

Governor Holden's trial convened in the state senate chambers on January 23, 1871, and remained civil though hardly unbiased. The trial concluded with Holden's conviction on six out of eight counts on March 22. The senate then quickly voted to remove Holden from office and barred him from holding any other public office in the state. Holden's political career was over.

Conservatives likewise targeted Colonel Kirk, burying him under a mountain of civil suits alleging false arrest. To protect himself from vigilantes, Kirk arranged his own arrest by a U.S. marshal, who carried him under guard to Raleigh. Kirk remained in the state capital until December when a Federal judge threw out the case against him. He originally returned home to Tennessee but quickly relocated to Washington, D.C., to accept a job as an officer with the police force.

Photograph of Josiah Turner Jr. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History.

The Way of War

The Way of War

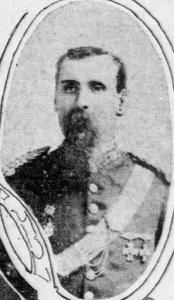

If Governor William Woods Holden was going to win a war against the Ku Klux Klan, he was going to need allies who knew how to fight. One of the first men he recruited was a former Union bushwhacker named George W. Kirk. Kirk was a well-known guerilla fighter who led raids into Western North Carolina during the Civil War. He and his troops—known informally as Kirk's Raiders—sabotaged Confederate railways and attacked unsuspecting Confederate units with reckless abandon.

This rough and tough attitude appealed to Governor Holden, who picked Kirk to command the militia and gave him the rank of Colonel. Colonel Kirk organized his forces and targeted areas of high Klan activity to enforce Governor Holden's martial law. Moving from county to county, Colonel Kirk and his second in command Colonel George B. Bergen arrested local Klan leaders and restored order. Despite the gains, Governor Holden's effort required more support, prompting him to reach out to an important potential ally for help.

Portrait of George W. Kirk, circa 1901. Courtesy of The San Francisco Call

Portrait of President Ulysses S. Grant. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

On July 20, 1870, Governor Holden wrote President Ulysses S. Grant requesting additional support, mainly in the form of Federal soldiers. Governor Holden supported his request with three important points: the militia was largely outnumbered, the deployment of African American militia would likely lead to increased violence, and that it was impossible to find enough white men who supported his cause.

Governor Holden also argued that the presence of Federal soldiers in North Carolina would be enough to deter members of the Klan. President Grant agreed. In a letter dated July 22, he assured Governor Holden he had his support and directed Secretary of War William Worth Belknap to deploy Federal troops to North Carolina.

The use of troops to suppress Klan activities in North Carolina was very effective. Colonel Kirk and his militia forces arrested around 100 members of the Klan and successfully broke up Klan activity in both Caswell and Alamance Counties. Despite their success in restoring law and order, the soldiers' presence wasn't entirely welcomed. Opposition to Governor Holden's use of troops led many Conservative newspapers to relentlessy attack the anti-Klan campaign, their columns often exaggerating or outright fabricating alleged outrages and mistreatment by Holden's forces. Governor Holden's campaign to arrest Klan members was a success, to be sure, but on the frontlines of the battle in the media, he met a formidable foe: Josiah Turner, Jr.

Portrait of U.S. Secretary of War William W. Belknap. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

A Declaration of Insurrection

A Declaration of Insurrection

Violence by the Ku Klux Klan within North Carolina had been increasing over the course of 1869, an attempt to curb the political influence of white Republicans and the newly won civil rights of Black citizens. Klan members largely targeted Black men, women, and children. Among the earliest victims of Klan violence during Governor Holden's administration was Daniel Blue.

Blue was an African American man who resided in Moore County with his family. In February 1869, the Klan entered the family's home and murdered Blue's wife and children. After the murders, Klan members burned the house—with the bodies of the deceased still inside—to the ground.

Photograph of hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan, c. 1870. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

Photograph of the Caswell County Courthouse in Yanceyville. Courtesy of Jimmy Emerson, DVM.

Influential African American politicians were also targeted by the Klan. On February 26th, 1870, a Black U.S. Army veteran and town commissioner named Wyatt Outlaw was lynched by Klan members on the grounds of the Alamance County courthouse. Wyatt had committed no particular "crime," a Klan member later testified. He was hanged simply "because he was a politician."

As winter turned to spring, the Klan continued their campaign of murder and terror. However, the act that would prompt Governor Holden to declare war on the Klan was the murder of John Walter Stephens.

John Walter Stephens was a prominent Republican senator from Caswell County. Despite being warned not to attend the 1870 Democratic convention at the Caswell County courthouse, he attended anyway. Stephens was at the courthouse supporting his friend Frank Wiley in an attempt to get him to run for Sheriff of Caswell County on a Republican ticket. Unknown to Stephens, however, Wiley had already made a deal with the Klan. Wiley lured Stephens into an office, where Klan members subjected him to a mock trial. Finding him "guilty" on charges of arson and extortion, the Klan then murdered Stephens and left his body in the courthouse.

The Klan's previous outrages had certainly horrified Governor Holden, but the brazen murder of Stephens, who was a legislator at the time of his death, compelled him to escalate his response dramatically. It was time to fight back. Invoking the recently passed Schoffner Act—championed by Republican state senator Tetman M. Schoffner of Alamance County—Governor Holden declared the counties of Alamance and later Caswell to be in a states of insurrection and deployed militia forces to round up and arrest Klan members.

A Ku Klux Klan mask from c. 1870-1872. Masks were designed to conceal the wearer's identify and terrorize the group's victims. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History.

Locke Craig

A selection of the papers of Governor Locke Craig, whose term in office spanned from 1913 to 1917.

Source: State Archives of North Carolina, via Flickr.

The Papers of

Governor Locke Craig

Known popularly in his time as the "Little Giant of the West," influential Asheville attorney and legislator Locke Craig rose to the governorship in 1913.

Fast Facts

→ graduated from the University of North Carolina, 1880

→ licensed to practice law, 1882

→ member of the North Carolina House of Representatives, 1899–1901

→ served as Governor of North Carolina, 1913–1917

A Complicated Legacy

Slowed by chronic illness and heartsick for the mountain-etched skyline of his home in Asheville, perhaps no man was ever more prepared to end his term as governor than Locke Craig. From 1913 to 1917, Craig tirelessly navigated the state through the most pressing issues of his day: the building of a network of good roads, the creation of the State Park System with the conservation of Mount Mitchell, and the rebuilding of Western North Carolina following the 1916 flood, to name a few. His turn in the governor’s mansion saw great personal changes and challenges too—the deterioration of his health, the death of his close friend and executive secretary John P. Kerr, and the birth of his son, Locke Craig Jr., late in his own life.

As much as we might admire Craig’s deft ability to triumph over complicated and lifechanging obstacles, we, as scholars of his political career, must also confront his unabashed dedication to the cause of white supremacy. It was Craig, after all, who stood shoulder to shoulder with Charles Aycock in launching the “campaign for the white man” at Laurinburg on May 12, 1898. Hitting the speakers circuit that summer with other prominent self-identifying white supremacists, Craig whipped white citizens into a racist frenzy. The bigoted fervor culminated in the violent murders of an untold number of Black North Carolinians and a suspension of Black voting rights that remained in place until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

So, when placed in proper context, what are modern North Carolinians to make of Governor Craig’s legacy? The goal of this project is not necessarily to answer that question for today’s citizens and scholars, but rather to equip them with the primary sources necessary to examine his administration—and, more importantly, his words—for themselves. Over 500 transcribed and annotated documents shed light on the most significant themes of his time as governor.

Now Available!

_0.jpg)

.jpg)