Project Mercury

Mercury-Redstone 3, carrying astronaut Alan B. Shepard and his capsule Freedom 7, launched on May 5, 1961. Courtesy NASA.

America’s first man-in-space program ran from 1958 to 1963 and was known as Project Mercury.

Through Mercury, NASA sought to achieve three objectives: to successfully orbit a manned spacecraft, to study man's ability to function in space, and to return both man and spacecraft safely back to earth.

The Mercury program culminated in six successful “manned” missions. Some of Mercury's earliest testing, however, was completed by one unlikely astronaut with ties to the Tar Heel State.

Ham, the Astrochimp

On January 31, 1961, an African-born chimpanzee named Ham successfully completed a 16-minute, 39-second suborbital flight. Traveling close to eight times the speed of sound (more than 6,000 miles per hour), Ham reached an altitude of 157 miles above the Earth’s surface.

In those sixteen minutes, Ham completed a series of simple tasks, manipulating levers, switches, and knobs in a certain order, proving that fine motor tasks could be completed at all stages of spaceflight, from launch to landing. His success demonstrated that manned space flight could be safely accomplished; three months later, Alan B. Shepard Jr. followed him into space.

In 1963, Ham was transferred to the National Zoo in Washington, DC, where he lived in relative isolation for seventeen years. Noting his loneliness, advocates arranged for Ham to relocate to the North Carolina Zoo in 1980 where he lived out the rest of his life surrounded by fellow chimpanzees. He died two years later, a national hero.

NASA tested the Mercury-Redstone system with a chimpanzee named Ham before sending Alan B. Shepard into suborbital flight. Courtesy NASA.

On January 21, 1961, Ham climbed into his specially-made primate capsule and was loaded into the larger Mercury capsule. Courtesy NASA.

Perched atop a Redstone rocket, Ham took his first and last spaceflight on January 21, 1961. Courtesy NASA.

Commander Ralph A. Brackett, of Gastonia, welcomes Ham aboard the recovery ship USS Donner following the successful flight of Mercury-Redstone 2. Though he was recovered in good condition, Ham experienced an alarming amount of distress during the course of the flight. Courtesy NASA.

Ham and a handler review gear and equipment ahead of the Mercury-Redstone 2 launch. Courtesy NASA.

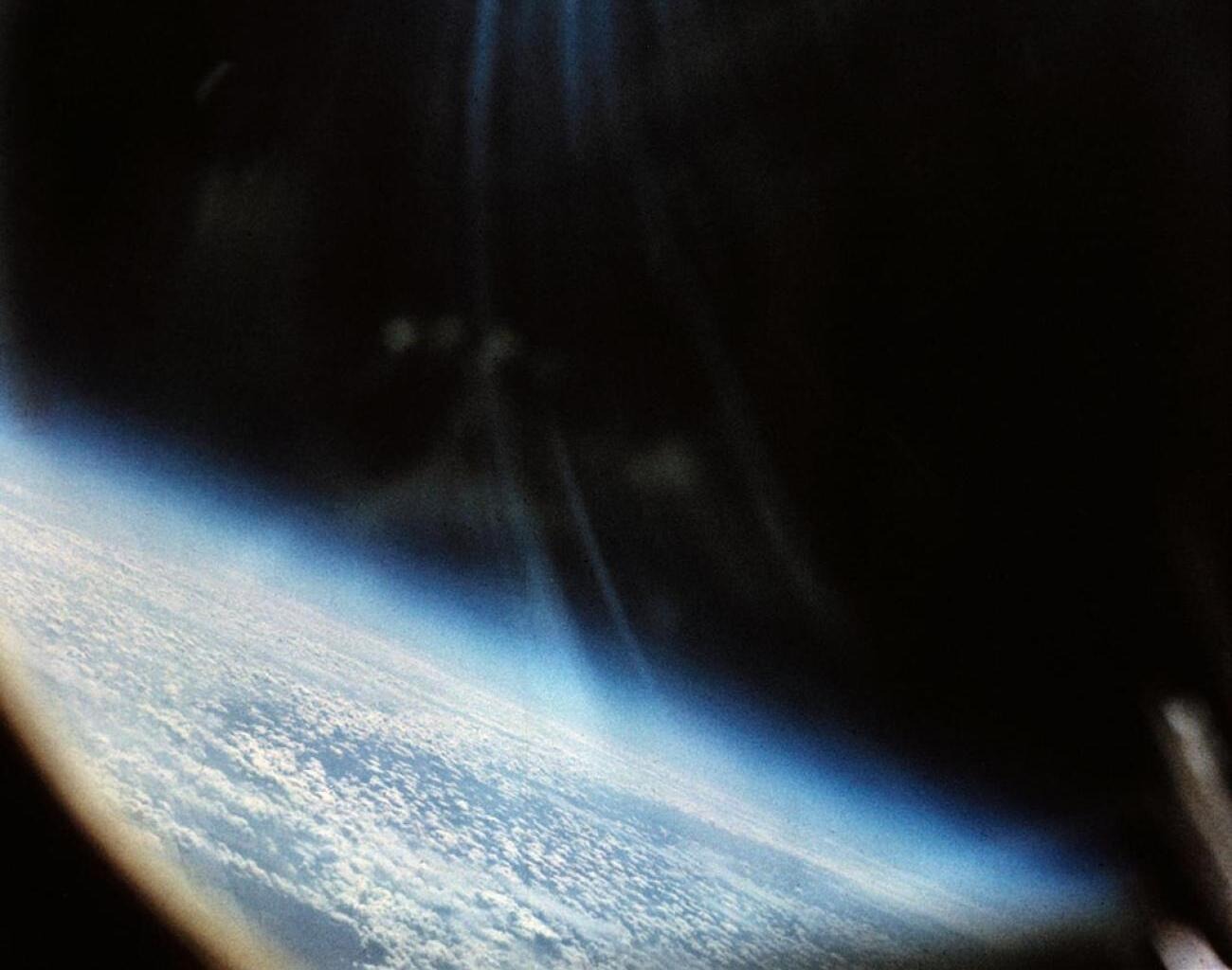

Ham's Mercury-Redstone 2 flight carried him to a height of 157 miles above the Earth's surface. From this altitude, the curvature of the Earth and the darkness of space were both visible from the window of Ham's spacecraft. Courtesy NASA.

After splashdown, Ham's capsule was retrieved by Marine Corps helicopter pilots and carried to the deck of the USS Donner, where recovery personnel set about removing the capsule hatch. Courtesy NASA.

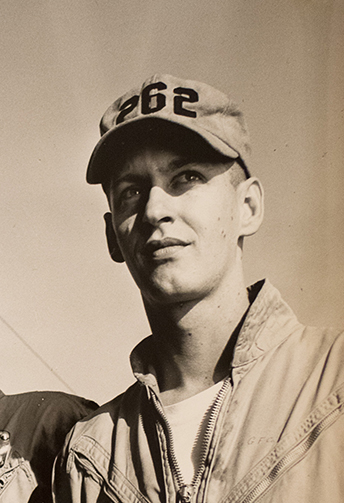

George Cox, of Newport, North Carolina, assisted in the recoveries of astronauts Alan Shepard and Virgil "Gus" Grissom. Courtesy George F. Cox.

Early Capsule Recovery

Aviators from helicopter squadron HMR-262 stationed at the Marine Corps Air Station New River in Jacksonville, North Carolina, were crucial in developing early recovery procedures for Project Mercury. Pilot Wayne Koons, of Kansas, and co-pilot George Cox, a long-time resident of Newport, North Carolina, drew national attention for recovering astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. and his spacecraft Freedom 7, during Mercury-Redstone 3. Their experiences informed recovery planning up through the end of Project Apollo.

Helicopter 44, of Marine Corps squadron HMR-262, served as the primary recovery vehicle for Mercury-Redstone 3. Newport resident George Cox can be seen in the cargo opening. Shepard and his capsule, Freedom 7, hang tethered below the craft. Courtesy NASA.

Eleven minutes after splashdown, Wayne Koons and George Cox moved in to recover Freedom 7 and astronaut Alan B. Shepard. Here, Cox winches up Shepard, as the Freedom 7 capsule hangs below. Courtesy NASA.

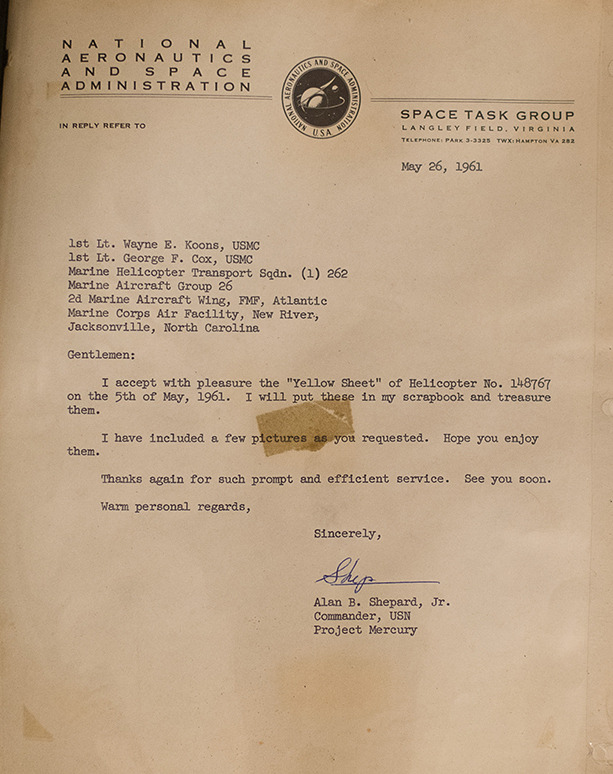

This letter from astronaut Alan B. Shepard to pilots Wayne Koons and George Cox thanks them for their "prompt and efficient service" during the recovery efforts of Mercury-Redstone 3. Courtesy George F. Cox.

During the recovery of Mercury-Redstone 4, the hatch of astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom's Liberty Bell 7 capsule jettisoned prematurely. Water poured into the capsule as Grissom made a desperate escape. Helicopter 32, of HMR-262, managed to hook the capsule and attempted to pull it out of the water. Water can be seen pouring from the hatch opening in this photo. Courtesy NASA.

George Cox's helicopter, number 30, flew in to rescue a drowning Grissom, whose suit had filled with water. As co-pilot on the mission, Cox operated the winch that pulled Grissom to safety. Courtesy NASA.

James L. Lewis, pilot of helicopter 32, was forced to cut the flooded Liberty Bell 7 loose when an alarm sounded. The capsule sank three miles to the ocean floor and remained there until it was recovered by salvage experts in 1999. The recovered capsule is pictured here following the salvage operation on July 21, 1999. Courtesy NASA.

Official portrait of Samuel Beddingfield, taken June 18, 1963. Courtesy Nan Lafferty.

Engineering Mercury

Clayton native Samuel Beddingfield joined NASA as an engineer in 1959, becoming one of only thirty-three agency employees assigned to Cape Canaveral, Florida, at that time. During Mercury, Beddingfield oversaw mechanical and pyrotechnic operations, including the deployment and jettisoning systems for landing parachutes and capsule escape hatches. He concluded a twenty-six-year-career with NASA in 1985, when he retired from the agency as the deputy director of the space shuttle program at Kennedy Space Center.

During Mercury, a large part of Beddingfield's responsibilities included ensuring proper weight and balance of the capsule. Here, he can be seen installing rockets (seated on crate, right), alongside several colleagues, during the weight and balance process ahead of Mercury-Atlas 1 on July 25, 1960. Courtesy Nan Beddingfield.

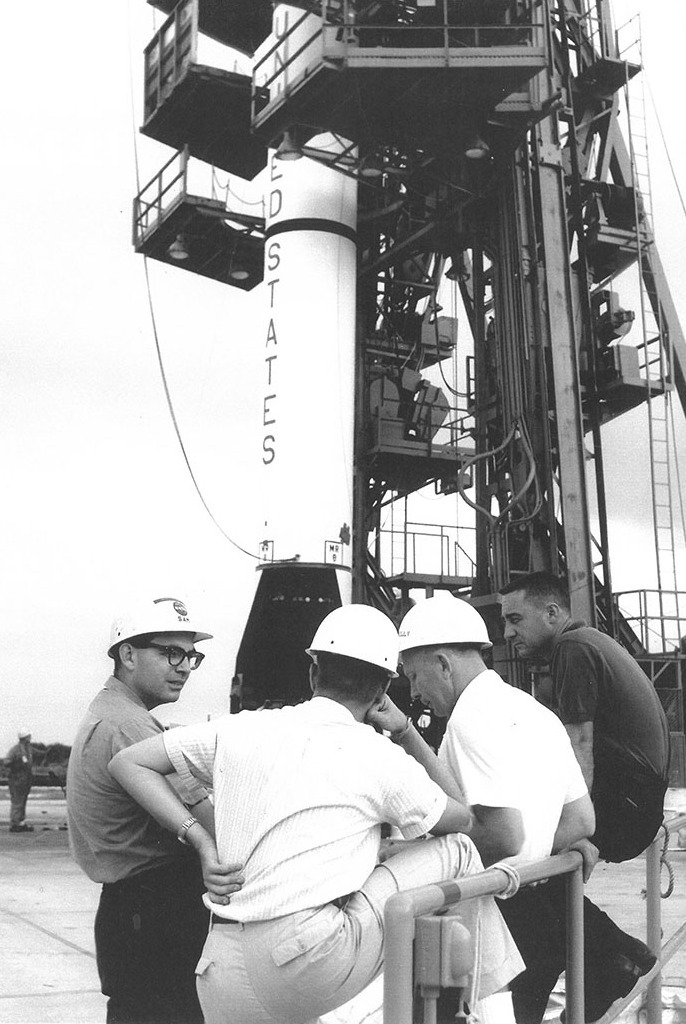

Beddingfield and Gus Grissom had been good friends ever since their days at Wright Patterson Air Force Base. Beddingfield, far left, talks with two unidentified colleagues and astronaut Gus Grissom, far right, ahead of the Mercury-Redstone 4 flight. The Redstone rocket that carried Grissom into suborbital flight can be seen in the background. Courtesy Nan Lafferty.

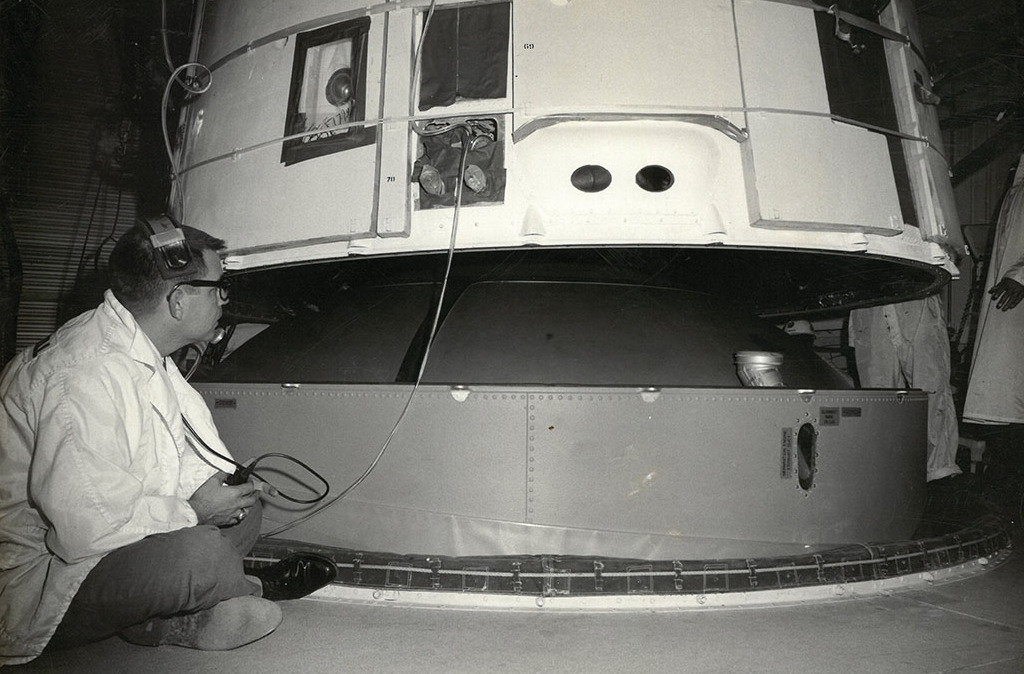

Following the successful flight of Mercury-Atlas 6, Beddingfield (crouched beneath capsule, holding book) and colleagues inspected the Friendship 7 capsule. Courtesy NASA.

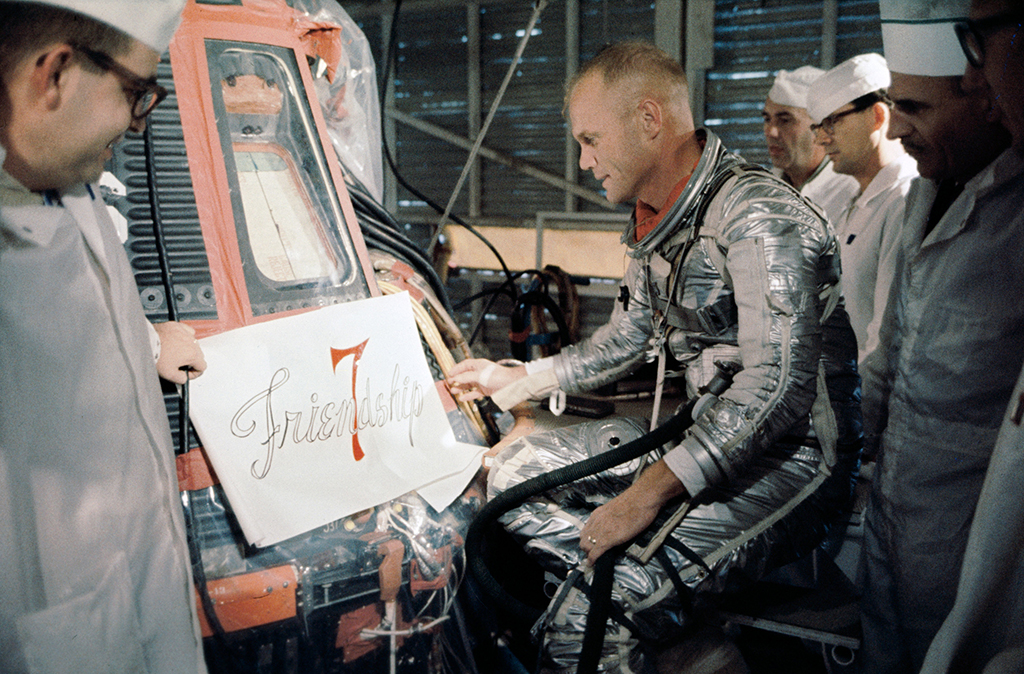

On February 20, 1962, Beddingfield (far left) presented the graphic design work for Friendship 7 to astronaut John Glenn (center) ahead of America's first orbital flight. Courtesy NASA.

Beddingfield, right, and two other engineers run through the weight and balance process with astronaut Walter Schirra on July 7, 1965, ahead of his Mercury-Atlas 8 flight. Courtesy Nan Lafferty.

In the white room on Pad 19, Beddingfield observes the "hard mate" of Gemini-Titan 3 on February 17, 1965. Courtesy Nan Lafferty

Beddingfield and another man inspect parachutes for a Gemini flight on September 19, 1966. Courtesy Nan Lafferty.

The most trying time of Beddingfield's career came in 1967, when fire erupted inside the Apollo 1 capsule, claiming the lives of Ed White, Roger Chaffee, and Gus Grissom. In a 1983 interview, Beddingfield reflected briefly on the accident, his grief over the loss of his good friend Grissom still palpable: "That was the most traumatic thing for me. At that time, I was responsible for the emergency egress." Following the accident, Beddingfield was charged with overseeing the disassembly and storage of the capsule, a job that took six months. Courtesy Nan Lafferty.