Exhibit Sections

Image

Project Apollo

Project Apollo’s ultimate goal—to put a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth—was achieved just eight years after President John F. Kennedy’s challenge, a testament to American ingenuity and perseverance.

Between 1969 and 1972, twelve men walked on the Moon. This feat, however, could not have been achieved without the support of hundreds of thousands of Americans from a wide range of professions. North Carolina engineers, mathematicians, manufacturers, scientists, and aviators all contributed greatly to the successes of Project Apollo.

Image

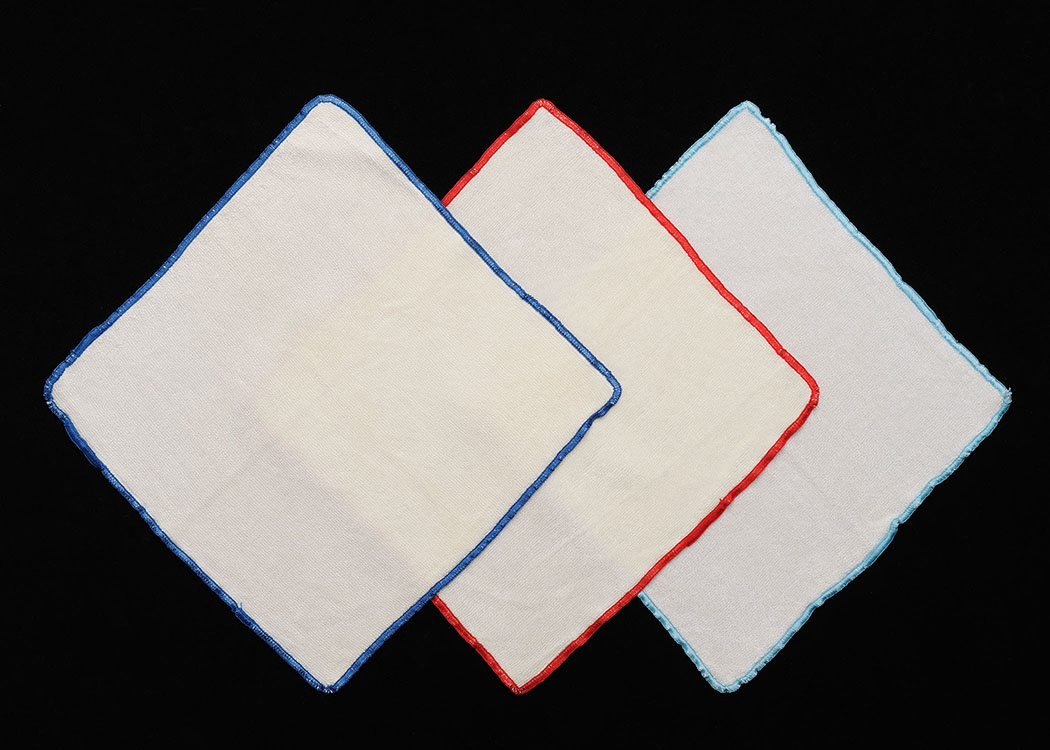

Medicine, mission patches, and special alloys—the contributions of North Carolina manufacturers, though limited in number, cannot be overlooked. From 1961 to 1972, when the final Apollo mission was flown, NASA awarded state-based contractors more than $23,000,000 in contracts.

Image

Human Computers

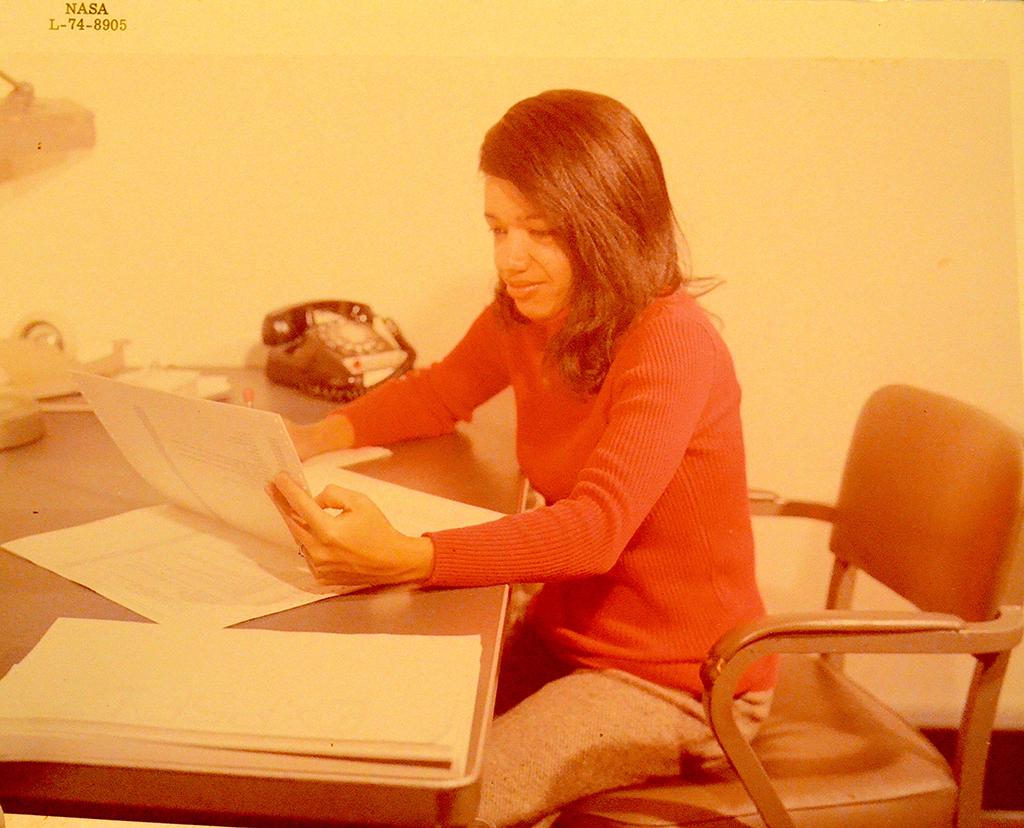

In the early days of NASA, people—not devices that provided instant results—performed the mathematical calculations necessary to put a man in space. Women, including some from North Carolina, comprised the majority of these “calculators,” or “computers,” taking on work originally performed by engineers. Their tools of the trade were not electronic, or even necessarily electric; they were likely hand-manipulated slide rules, spring-loaded calculating machines, pencils, and paper.

By the time of Apollo, the arrival of computing machines—the beginnings of today’s computers—had revolutionized their work, and many women transitioned into computer programming.

Exhibit Text

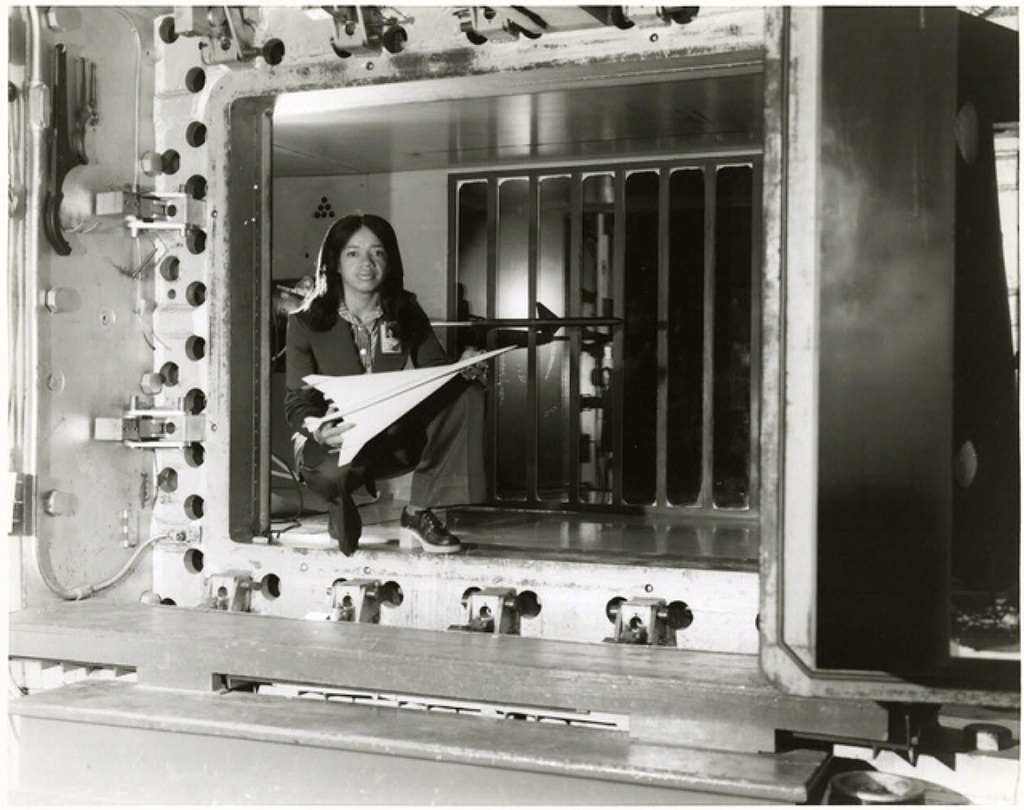

The short film above, appearing here courtesy of Scholastic, explores the life and career of Union County native Christine Darden. Dr. Darden's NASA career—from data analyst to aeronautical engineer—was profiled in the book Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, by Margot Lee Shetterly.

Image

An Army of Contractors

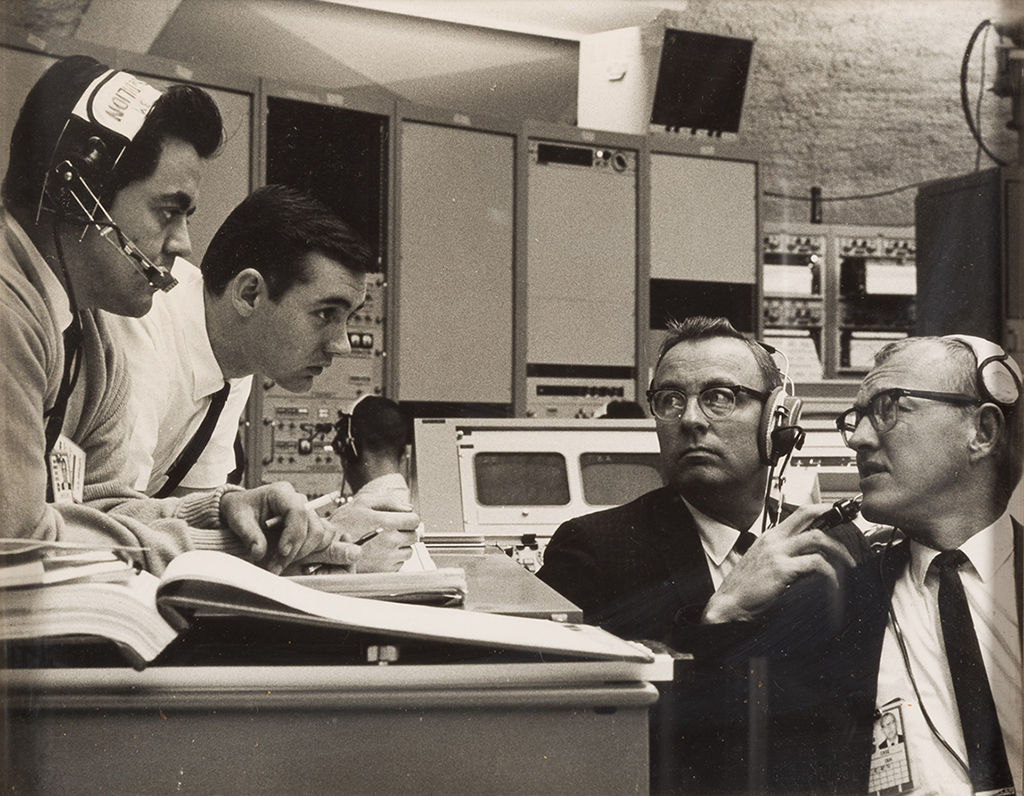

Not everyone who supported NASA’s efforts to go to the Moon worked for the agency directly. Companies representing a variety of fields from all around the country entered into contracts with the federal government to supply NASA with specialized knowledge and technology. At the height of the space race, the number of contracted employees reached into the hundreds of thousands. It remains a mystery just how many North Carolinians helped put a man on the Moon without ever brandishing the NASA logo.

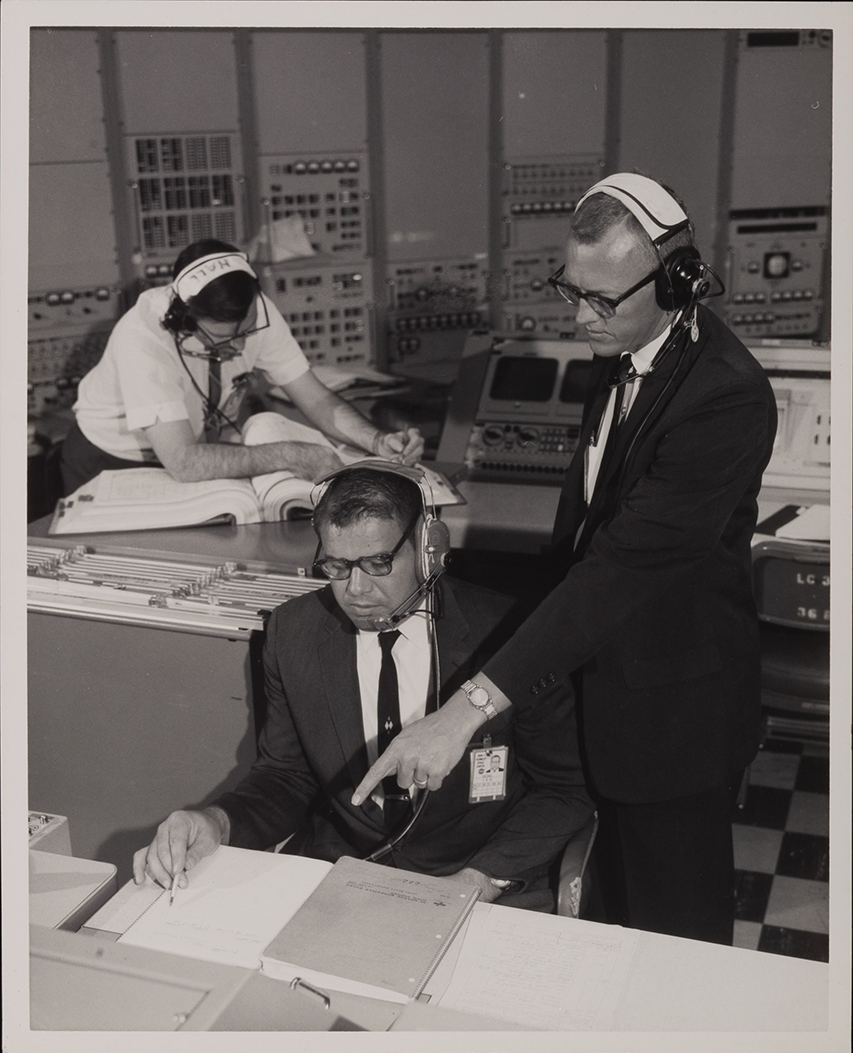

In 1966, Arthur B. "Art" Case, who later retired to North Carolina, was considered to be one of the “five…most important IBMers” at Cape Kennedy in Florida. From the relative safety of the blockhouse, Case and his fellow IBM test conductors were responsible for the final checks of the launch control equipment in preparation for vehicle liftoff. It was a high-pressure, high-stakes job, an environment in which Case seemed to thrive. As manager of Complex 34 during the Saturn IB program, Case witnessed firsthand both the tragedies and triumphs of the American space program.

Image

Charles Duke and Apollo 16

Charles M. “Charlie” Duke is the only man with North Carolina ties to have walked on the Moon. Though born in Charlotte, Duke was raised across the state line in his parents’ home state of South Carolina. He went on to graduate from the United States Naval Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1966, at the age of thirty, Duke was one of nineteen men selected for Astronaut Group 5.

In 1972, Duke served as the lunar module pilot for the Apollo 16 flight. Mission commander John Young accompanied Duke to the lunar surface. Together, Duke and Young collected samples and conducted a series of experiments in the Descartes Highlands, a crater-pocked region on the near side of the Moon, from April 21 through 23, 1972. The team remained on the lunar surface for seventy-one hours.

Image

Geological Investigation

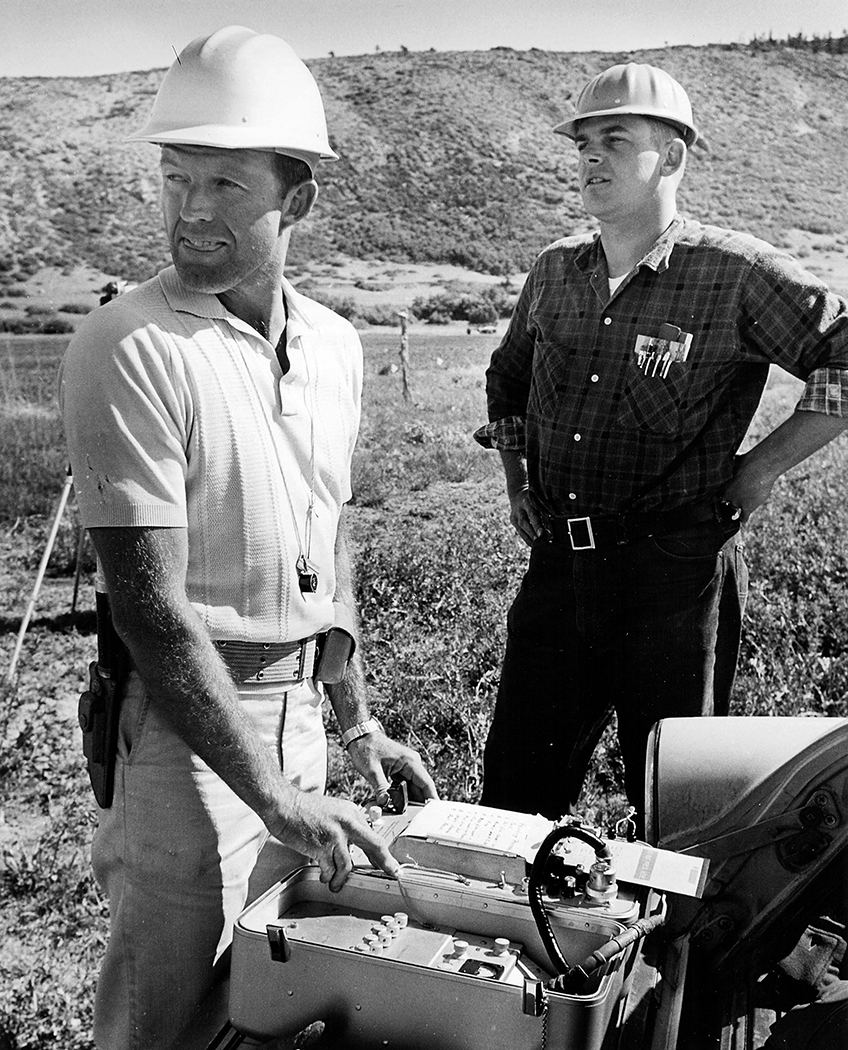

Due to a medical condition, UNC Chapel Hill alumnus and professor Dr. Joel S. Watkins was declared medically ineligible for NASA’s scientist-astronaut program—the same program that put fellow geologist Harrison Schmitt on the Moon. Undeterred, Dr. Watkins sought alternative means of supporting geological and geophysical study of the lunar subsurface.

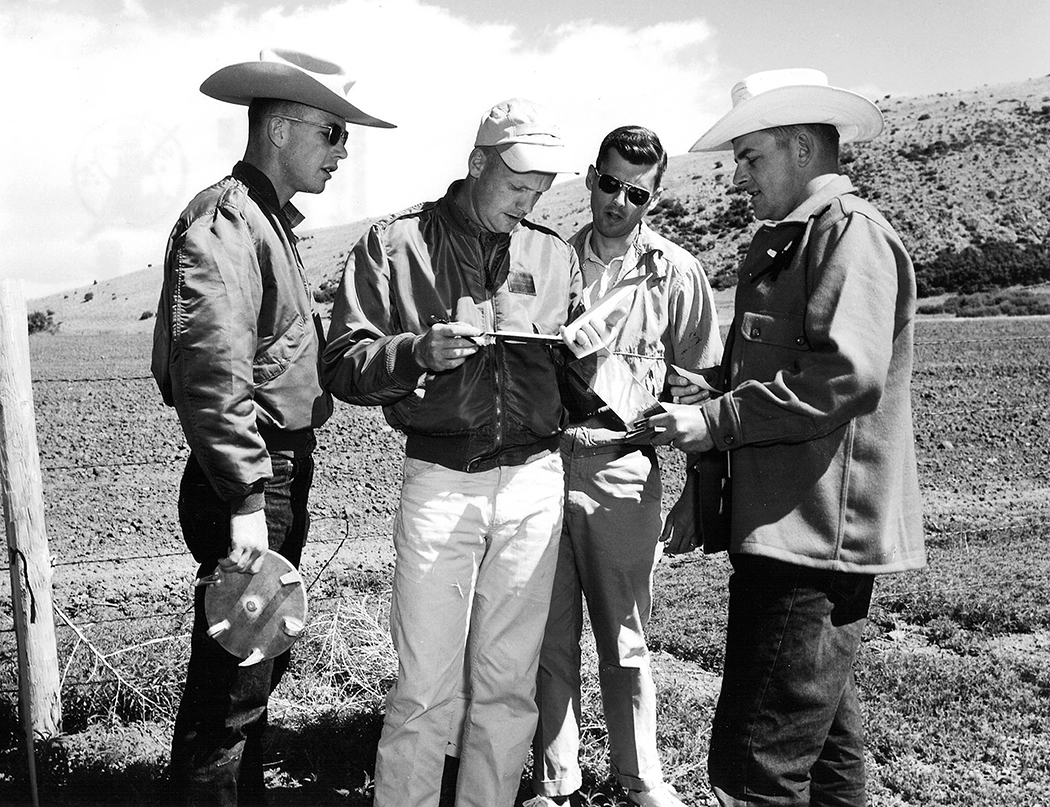

In June 1964, Dr. Watkins and colleagues from the Astrogeology Branch of the US Geological Survey conducted a geological field school at the Philmont Scout Ranch in northern New Mexico. There, they trained Apollo astronauts in geologic mapping, field note documentation, and how to analyze subsurface structure using magnetometers, seismometers, and gravimeters.

And though he could not make the trip through space himself, Dr. Watkins found another way to contribute to man’s investigation of the Moon’s physical makeup. During Apollos 14, 16, and 17, astronauts deployed devices developed by Watkins to measure moonquakes. The results of those experiments are still being analyzed today, to deepen our understanding of the Moon’s composition.

Image

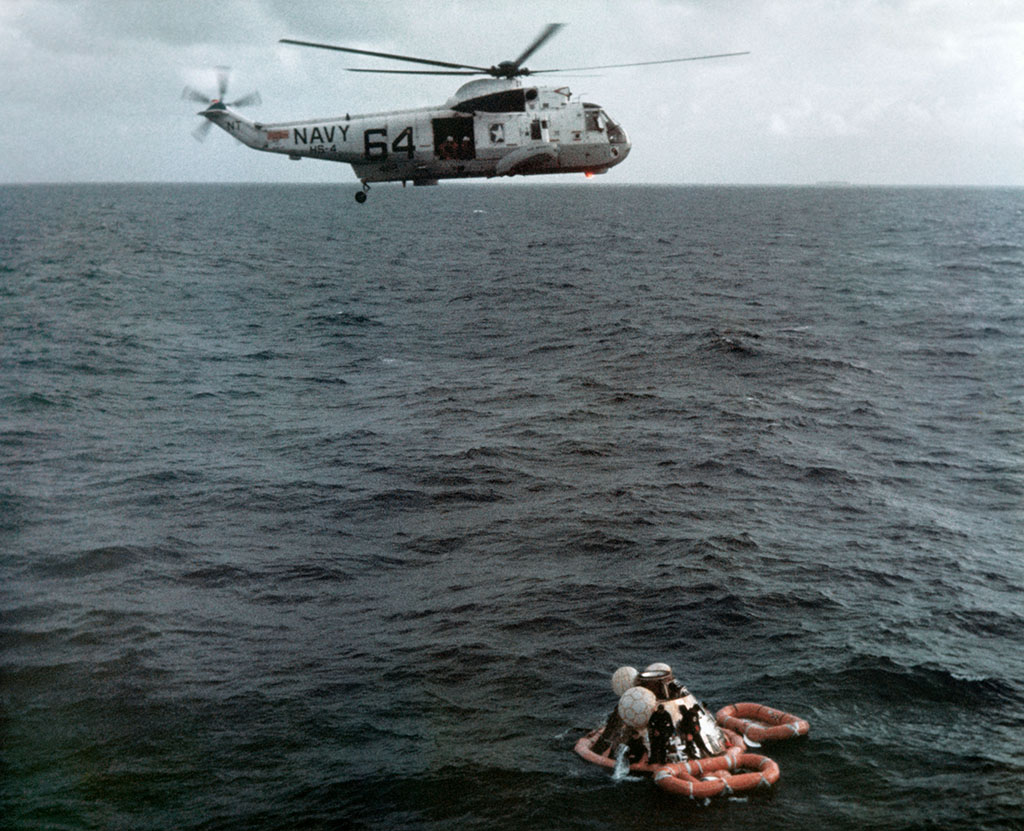

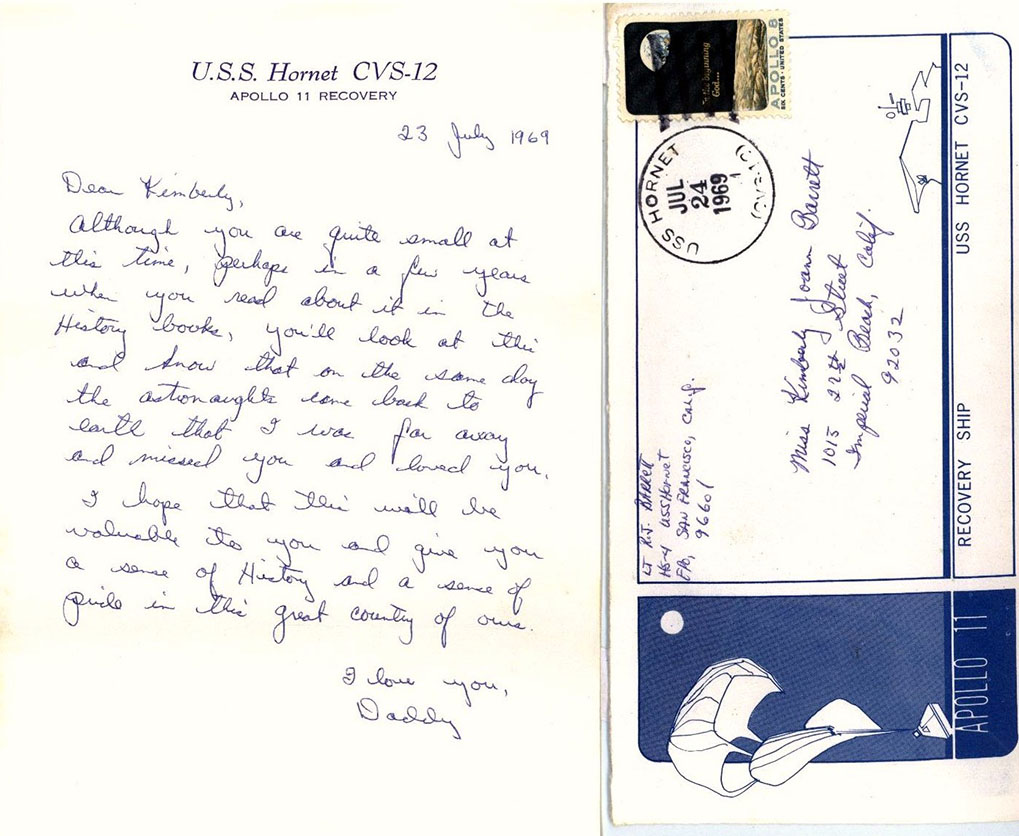

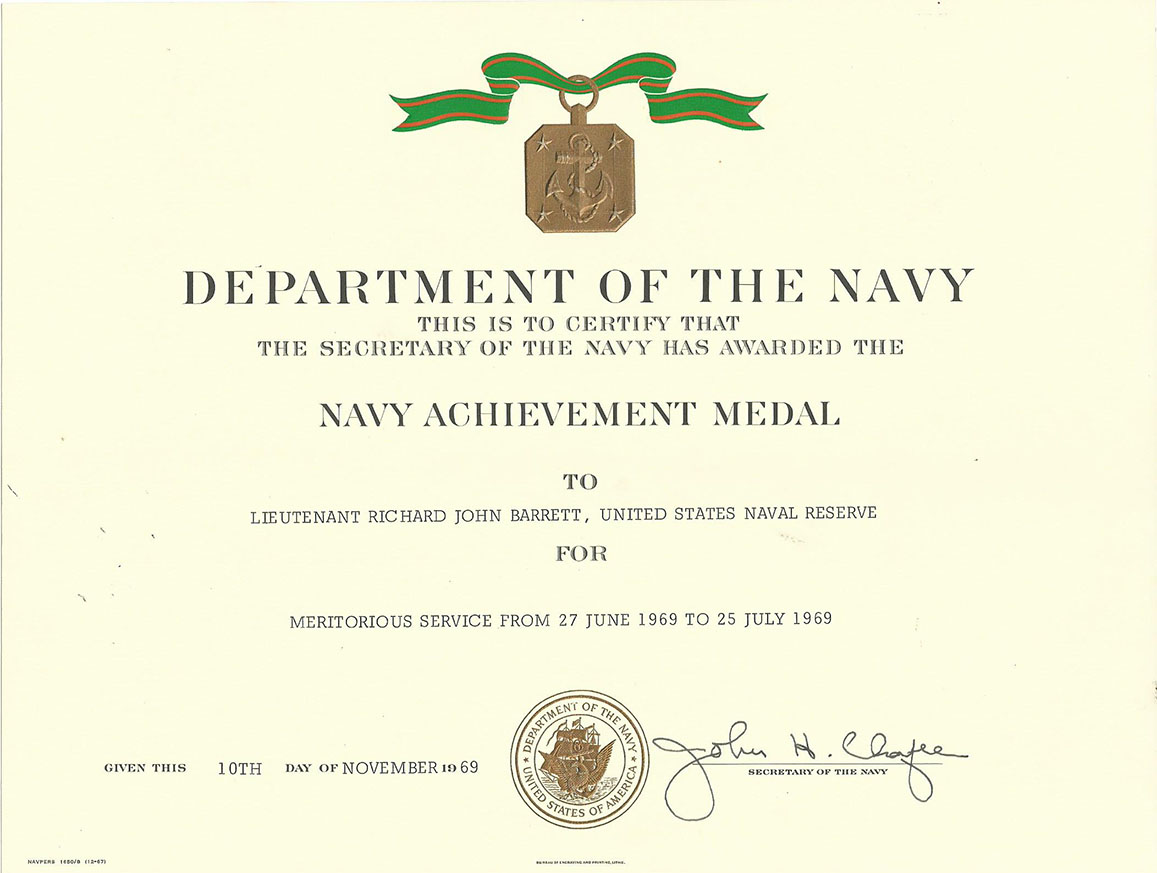

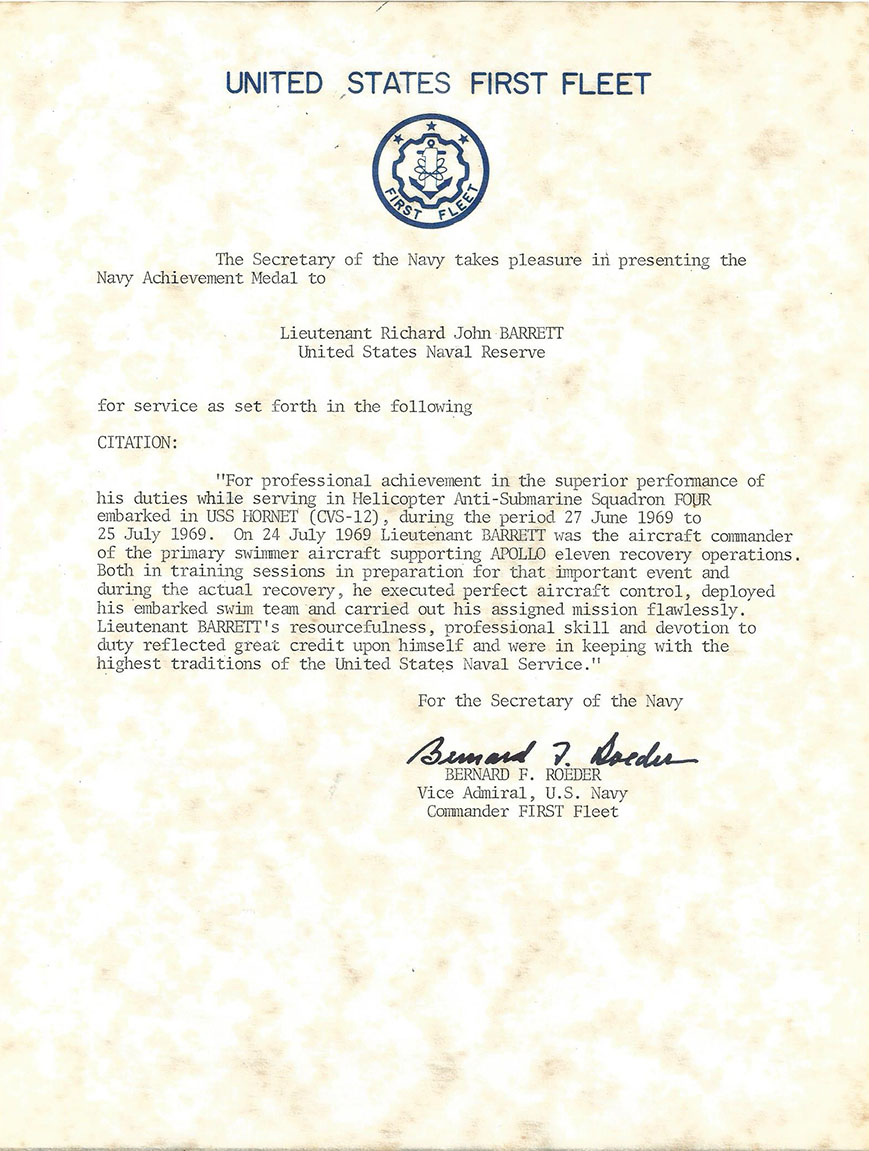

Astronaut Recovery

After Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 capsule sank—and he nearly drowned—during the second manned Mercury mission, NASA worked closely with military partners to overhaul recovery protocol. As a member of Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Four (HSC-4), Lt. Richard J. Barrett—who grew up in Asheville and Canton—contributed to the development of search and rescue procedures for early manned Apollo flights.

Though he participated in the recoveries of Apollos 8 and 10, it was his involvement in helping to develop and execute search and rescue procedures for Apollo 11 that is perhaps most firmly etched in his mind. Piloting helicopter 64 that July day in 1969, Lieutenant Barrett skillfully and expertly dropped Navy swimmers and important gear next to the bobbing Apollo 11 capsule.

Exhibit Text