Running away or committing physical assaults were a means towards agency for enslaved people, but they also were illegal actions. Some enslaved individuals preferred a slower, though legal, route. By appealing to the government directly, manumission petitions were a means for enslaved people to advocate for themselves and fight for freedom.1

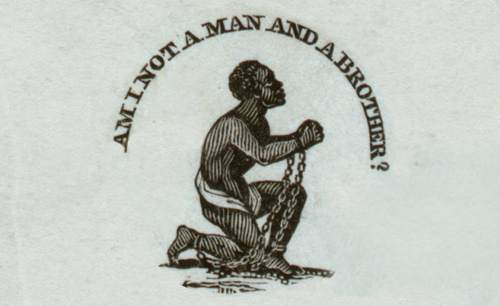

Inscribed with the message "Am I not a man and a brother?" this medallion was designed as by Josiah Wedgewood for the Anti-Slavery Society in 1787. The icon of the African American man kneeling in chains helped to rally people toward the cause of abolition. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Enslaved people performed vital services to their communities, seeking freedom as a reward.

When petitioning for their freedom, many enslaved individuals relied on endorsements of support from their local communities. By demonstrating that they had their neighbors’ goodwill, enslaved individuals attempted to ease officials’ concerns, showing that their freedom would not cause issues. In addition to citing a long history of good behavior, some enslaved individuals also pointed to vital services they did for their communities.

Peter, an enslaved man of African American and American Indian descent, collected signatures from his neighbors in Perquimans County for his freedom petition. Peter’s community attested that he had no criminal history, and, in fact, was an asset for the surrounding populace. Locals depended on Peter, an expert tracker and hunter, to kill dangerous wild animals that threatened their livestock such as “Bears, Wolves, Wild Cats, & Foxes.”

The outcome of Peter’s petition was not recorded, but his case exemplifies how enslaved people emmeshed themselves within communities and provided vital services despite being in bondage. They then used that social capital when it suited them, such as collecting support for their applications for freedom.

Many African Americans, both enslaved and free, hunted in and traversed the dangerous wilderness. Courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia.

Not all enslaved people's freedom petitions were equally successful.

Many enslaved people attempted to gain their freedom through legal means, but not everyone was equally as successful. One unsuccessful applicant was Amy Demsy, a woman of mixed African American and white ancestry. Even though her mother was free, the law required that Amy serve as an indentured servant until she reached a majority because of her mixed-race identity.

Sometime during her childhood, Demsy was sold to Nathaniel Duckenfield of Bertie County, with the understanding that she’d work for him until she reached the age of thirty-one. However, when Demsy reached the age of twenty-one, she made an appeal to the North Carolina Colonial Court, questioning the system of indenture altogether.

Having already labored at the Duckenfield plantation for at least a decade, Demsy had already paid off the ten pounds Duckenfield had paid for her in the first place, she argued. Why should she continue to work for the Duckenfields for another ten years, just so they could continue to profit off her labor? Demsy’s petition was ultimately unsuccessful, and she only attained her freedom at age thirty-one, when more than half of her life had already passed. Still, her petition stands a testament to how enslaved and indentured African Americans questioned injustices within the system and advocated for themselves.

The Vestry of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Edenton, pictured above, hired out Amy Demsy's labor to the Duckenfields. Courtesy of SANC.

Military service during the American Revolution granted some enslaved individuals their freedom.

Enslaved individuals used petitions not only to apply for their own manumission, but also to ensure they’d be able to maintain their freedom. Such was the case for James, an African American man residing in Perquimans County. James had been enslaved by a prominent local Quaker named Thomas Newby. Morally opposed to slavery and no longer bound by British laws that had forbidden emancipation, in 1776 Newby and several other Quakers freed their enslaved people, including James.

The threats to James’ personhood should have ended there—he was legally manumitted, but in 1777 the North Carolina General Assembly passed a new law forbidding emancipation and declared that those enslaved individuals freed in 1776 were retroactively in violation of the new law.2 If Newby refused to take James back, then the law stated that James would be reenslaved and sold at public auction.

Rather than risking reenslavement, James took to the high seas, serving as a privateer in Patriot service during the American Revolution. After the war, Newby and several other prominent Perquimans citizens filed a petition, arguing that James ought to be allowed to remain free due to his meritorious military service. The petition was granted and James was able to live out his life as a free North Carolinian alongside his wife and children.

A privateer during the American Revolution, James might have sailed on a ship that looked like this one, illustrated on a 1733 map of North Carolina by Edward Moseley. Courtesy of East Carolina University Digital Collections.

- For a larger collection of Slavery Petitions from the American South, see the Race and Slavery Petitions Project, part of the Digital Library on American Slavery.

- For more information regarding Quakers, slavery, and Revolutionary North Carolina, see Michael J. Crawford, The Having of Negroes is Become a Burden: The Quaker Struggle to Free Slaves in Revolutionary North Carolina (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010).