Although in bondage, one way that enslaved individuals kept their traditions and culture alive was through the practice of a West African-based form of witchcraft called Hoodoo, Obeah, or conjuring.1 No matter what it was called, Hoodoo centered on herbal remedies (as well as poisons) and a series of rituals, which practitioners claimed would allow them to influence the environment around them, whether for good or for evil. By clandestinely practicing Hoodoo, enslaved individuals made choices for themselves, unbeknownst to their enslavers.

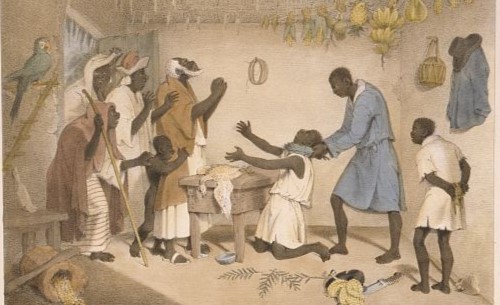

Illustration of a black magic practioner performing a ritual on a kneeling African American man. Enslaved North Carolinians kept African traditions alive by practicing hoodoo and other forms of folk magic. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Some enslaved people consulted with local magic practioners, called conjurers, who promised to subtly influence enslavers' behavior.

Hoodoo rituals in North Carolina, at least according to extant sources, typically centered on special plant roots. By using these plant roots, conjurers promised to help enslaved individuals improve their lives without their enslavers noticing. For example, in Johnston County, an enslaved conjurer named Bristoe promised an enslaved man named Tom that he could make Tom’s "master Buy his wife" from a neighboring enslaver if Tom chewed a special root. Similarly, an enslaved woman named Lucy also received a root from Bristoe when she asked him to make her enslaver not sell her to a faraway plantation.

Enslaved individuals also relied on conjuring rituals for other forms of protection against their enslavers. Bristoe performed a ritual for an enslaved man named Jacob. By rubbing a dust with supposedly magical properties into Jacob’s hand, Bristoe claimed to be able to "prevent [Jacob’s] master from whipping him." Conjurers claimed to be able to cast spells on enslavers directly as well. Another enslaved man named Jacob received a special talisman from a conjurer named Quash. By hiding the talisman at the threshold of his enslavers’ door, Quash promised Jacob that it’d make his enslaver treat Jacob more nicely.

Reliance on herbal remedies and magic rituals, whether effective or not, demonstrates how some enslaved people used unorthodox means to advocate for themselves and improve their living conditions.

Drawing of the Ipomoea purga, or Jalap root. Folk magic practioners believed that the root, sometimes called the High John the Conqueror root, had magical or medicinal properties. Courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library.

In additional to rituals, enslaved people also secretly used poisons on their enslavers.

An enslaved person might find themselves being owned by a variety of different individuals throughout their life, each of whom might treat the enslaved individual very differently. A change in ownership, whether desired or not, was often a source of immense anxiety for enslaved individuals. Such was the case for Daniel, an enslaved African American man living in Hyde County.

In the early summer of 1756, Daniel felt his life turn upside-down when his enslaver, Littleton Eborne, announced his marriage to Elizabeth McSwain. McSwain evidently had a reputation in the area as a cruel and strict owner. Daniel expressed his anxieties to another enslaved person named Peter, stating that Elizabeth McSwain, now Eborne, was "as Cross as the Devil" and refused to allow the enslaved people to eat pork.

Feeling as though Elizabeth Eborne’s treatment of enslaved people was intolerable, Daniel might have thought it was a sign when he found a dead rattlesnake. Taking it home, Daniel carefully cut off its head and dried it before grinding it up into a fine powder, which he secretly slipped into her "Victuals and Drink." By June 1756, she was dead. However, the secret was too much for Peter, who testified against Daniel, and Daniel was found guilty of murder.

19th century engraving of a rattlesnake. Daniel used a dead snake's venom to poison Elizabeth Eborne. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Enslaved people also used herbal remedies on themselves as a way to help them preserve their own bodily autonomy.

Herbal remedies and rituals were not always meant to influence enslavers. In some cases, such as Jane’s, an enslaved woman in Johnston County, they were a means of preserving bodily autonomy. In 1779 she sought out a local enslaved conjurer named Caesar. From Caesar, Jane received an herbal substance, referred to as "truck," which was supposed to work as a contraceptive.

In many cases, enslavers wanted their enslaved people to have children, as it’d be a means of increasing their workforce. Further, having children also made enslaved adults less inclined to try to self-emancipate themselves by running away. By seeking out contraception, Jane undertook a conscious step for herself, disregarding what her enslaver’s wishes might have been. By deciding on her own whether she wanted children, Jane exercised agency over her body and her future.

The motivations for some enslaved people's violent actions against their enslavers went unrecorded.

As historians, we can never know the full extent of an enslaved person’s thoughts and experiences. With the documents we do have, we can start to piece together details of a person’s life, but it is a puzzle that will always be missing some pieces. One such case for which we have more questions than answers concerns Esther, an African American woman in Chowan County who was enslaved by Anne Hall Blount.

Esther had been enslaved by Anne or her family for most of her life, and she was probably about the same age as Anne. Esther is likely the “girl named Easther” mentioned in Anne’s father Clement Hall’s estate inventory in 1759. In 1774 Esther was likely there to witness when Anne, along with her mother and sister, signed the Edenton Tea Party Resolves, a resolution in protest of Britain’s colonial taxation policies, wherein Anne and fifty other women gave their oaths to boycott British goods including tea. The Edenton Resolves were groundbreaking as a symbol of women’s activism during the American Revolution. Yet, it remains deeply ironic that these women signed their names in support of independence while the majority of them simultaneously were enslavers.

This 1775 satirical cartoon of the signing of Edenton Tea Party Resolves depicts several of the signers being waited upon by a person of color. Perhaps Anne Blount's enslaved woman, Esther, was present for the signing. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Esther might have acquired the verdigris she used to poison Anne Hall Bount from from a family medicine chest, similar to the one owned by a Maryland physician pictured above. Courtesy of NMAH, Gift of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of the State of Maryland.

While Anne boycotted British imports such as tea, she still relied on Esther to serve her food and drinks, amongst many other duties. We cannot be certain whether Esther herself recognized this irony. Whatever her reason, in 1779, just five years after the Edenton Resolves, when Anne asked Esther to prepare her a cup of tea, a task Esther had probably performed thousands of times before, something snapped in Esther.

That day, Esther slipped a secret ingredient into Anne’s tea—verdigris, a blue-green compound that was considered a medicine in the colonial era, which was meant, in small quantities, to induce vomiting. Esther hadn’t meant for the verdigris to be a tonic, however. Instead she meant to poison and kill her enslaver. Esther’s plot was uncovered however, and Anne survived the poisoning attempt. Did Esther have the irony of the Edenton Resolves in mind when she poisoned Anne’s tea specifically? We’ll never know for sure. But the question highlights what’s left to discover about North Carolina colonial history.

- For more information about conjuring, Hoodoo and other forms of magic, see Yvonne Patricia Chireau, Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Katrina Hazzard-Donald, Mojo Workin': The Old African American Hoodoo System (Champaign IL: University of Illinois Press, 2012). For more information on conjuring within North Carolina specifically, see Alan D. Watson, "North Carolina Slave Courts, 1715-1785," North Carolina Historical Review 60:1 (January 1983) 31.