Neutrality was difficult to maintain during the American Revolution, especially when both the Patriots and the British rejected the idea of a truly neutral party. Containing documents such as petitions, pension applications, and legal messages, this exhibit illustrates how North Carolinian Quakers experienced and contributed to the Revolution.

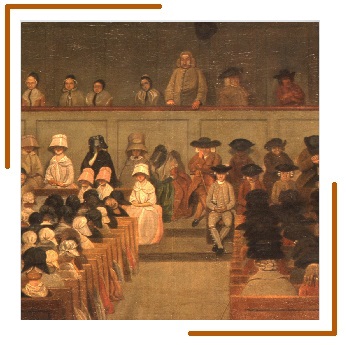

This painting of the Gracechurch Street Meeting, circa 1770, depicts a typical Quaker worship meeting. Courtesy of the Library of the Society of Friends.

Illustration of Patriots in the North Carolina Militia standing at attention.

The American Revolution is a classic underdog tale built on the desire for independence. Clashes were not limited to American colonists versus British troops. Colonists also fought each other as Patriots and Loyalists. Some colonists did not fight at all. Choosing not to fight aroused suspicion from both sides of the war. The Quakers are just one religious group that did not fight, but their other contributions are largely absent from the Revolution’s narrative. The Quaker experience in North Carolina was heavily shaped by both their philosophy and the public opinion of their refusal to engage in the war. The American Revolution would prove to completely disrupt the state’s established Quaker communities.

When North Carolina was founded as a religiously tolerant colony, Quakers flocked from Britain and New England. They believe the Spirit, or the Inner Light, resides in all living creatures. The Spirit guides from within, so worship does not require a minister. To take a human life is to work against the Spirit within that person, even for military purposes. All of these beliefs resulted in persecution from Anglicans and Puritans alike, which made the new colony of North Carolina very attractive to the Quakers. Many Quakers settled in the northeastern part of the state, especially in Perquimans and Pasquotank Counties. Other prominent Quaker communities settled in present day Wayne, Orange, and Guilford Counties. The same beliefs that had inspired the Quakers to relocate to North Carolina, however, would rattle the emerging government and clash with the population’s majority throughout the Revolution.

Patriots were deeply suspicious of Loyalists and concerned about the possibility of espionage during the Revolution. The emerging North Carolina government mandated that all state citizens swear an oath of allegiance to prove their loyalty and pledge themselves to the Patriot cause. In theory, there was no reason for someone to refuse the oath, unless they were a Loyalist. Therefore, if someone neglected to take the oath, their rights to property and legal action could be taken away.

The Quakers quickly threw a wrench in this plan for identifying Loyalists. The Quaker faith preaches that it is God’s decision and action to keep or topple governing bodies. Their human participation in the war would be a direct interference with the divine mission. Oaths in general are also seen as a form of forced honesty. Quakers believe in being honest in all circumstances, so they did not swear oaths. Furthermore, an oath of allegiance would be a decidedly military alignment.

Illustration of a man swearing a loyalty oath, as required by the state.

The Petition of Thomas Saint

This print, titled Quaker Lady Detaining the English General, depicts a woman entertaining British officers. Quakers would have welcomed anyone as a guest, regardless of military affiliation. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Though the North Carolina General Assembly acknowledged that Quakers would not swear the oath of allegiance, it did not exempt Quakers from the consequences in place for refusal. In 1778, a Quaker named Thomas Saint submitted a petition to the assembly regarding a land dispute. Saint had purchased a piece of land, but because he had not sworn the oath of allegiance, his claim had never been filed. A man named Benjamin Sherrard was now making moves on the land Saint had already paid for. Saint petitioned the assembly to allow him to file his land claim without an oath. It is unclear if the assembly granted Saint’s request.

The Quakers’ adamance that they could not serve in a militia was met with even more hostility than their refusal to swear an oath of allegiance. Many colonists were enraged that the Quakers refused to contribute to the war effort. Quakers conscientiously objected to military service no matter the side, but still some Patriots considered the Quakers as no better than Loyalists. Patriots often accused the Quakers of being secretly sympathetic to the British Crown. On the surface, the American militias were no match for the British forces; the Patriots needed all hands on deck for any chance of success. Some Patriots took the Quakers’ refusal to fight as a sign that they wanted the Patriots to lose the war.

The Battle of Guilford Courthouse occurred on March 15, 1781, in a predominantly Quaker community. Local Quakers sheltered in their homes as the fighting broke out.

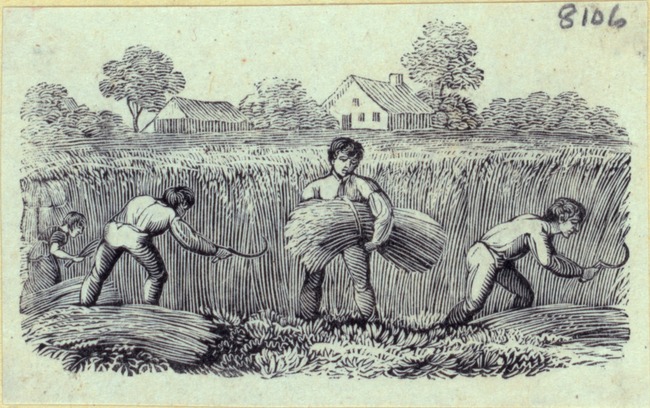

As required by legislation, Quakers provided wheat, a hot commodity during the Revolution, for the benefit of Patriot militias. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Noncombatants still contributed to the war effort by paying the property and provision taxes. Consequently, the North Carolina General Assembly—in an attempt to both appease and punish—raised the amount of taxes due from the Quakers and other noncombatants. In the tax collections, Quakers were now required to pay three times the amount of other citizens, and if they couldn’t, their property would be seized altogether. By increasing the taxes, the assembly thought, the Quakers would pull their weight in the war without having to muster in a militia.

Precedent from the Regulator Movement

The state’s extreme taxation on Quakers during the Revolution was unprecedented, but property and provision taxes were not novel concepts. North Carolina underwent the Regulator Movement from 1765 to 1771, in which some colonists, dissatisfied with Royal Governor William Tryon’s policies, organized an insurrection. Tryon’s militia defeated the Regulators (those who wanted more regulations on colonial power) in 1771. When Quakers refused to participate in the draft, Tryon found other means of having Quakers contribute to the war effort. In a 1771 letter, Tryon demanded that the Quakers of the Cane Creek community in Orange County provide six wagons of flour for his troops, along with teams of men to drive the wagons. Tryon specifically requested a wagon and team from one Quaker, John Pyle, who at the time was very active in the Regulator Movement. Pyle became a Loyalist during the American Revolution.1

Governor Tryon and the Regulators, engraving. Courtesy of the Bruce Cotten Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC Chapel Hill.

The Wayne County Quakers' Petition

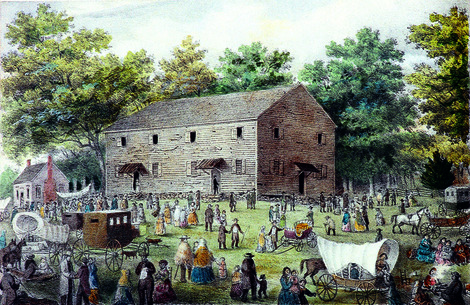

This painting, titled New Garden Meeting House, depicts the New Garden Quaker meetinghouse in Guilford County, North Carolina, during the colonial era. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The General Assembly’s conviction that Quakers deserved to pay three times the taxes in lieu of military service didn’t make the increase any less financially devastating to the Quakers themselves. Painfully aware of their dire situation, Quakers in Wayne County submitted a petition to the assembly in 1781, asking for a reconsideration of the taxation policy. The steep taxes had persisted long enough that Quakers had “to beg of our Neighbours, to give us leave to lie on their floors,” out of homelessness.

Despite the Quakers’ clear and respectful explanation of their dire circumstances, the Wayne County petition met with mixed results in the assembly. After some debate, the Senate ultimately argued that the law was clear: Quakers were required to pay three times the tax in lieu of military service, which would become a four-fold tax if the Quaker in question did not submit an inventoried list of taxable property. The Senate mentions a sevenfold tax while discussing the decision. Such an increase implies a tax collector's confusion on how the legal fourfold tax should be counted. Otherwise, a collector may have been particularly cruel to the Quakers by demanding a sevenfold tax. While it is unclear what legal action was taken to address the petition, the Assembly’s exchange indicates that being a Quaker in wartime did not immediately deprive someone of all of their rights. A Quaker could lose their property and their rights to it by not paying taxes or swearing an oath, but there was still a limit on how much would be required of them for a war they chose not fight in.2

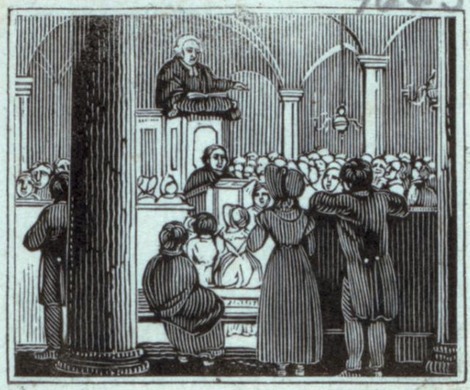

Engraving of a colonial courtroom. General Assembly proceedings operated similarly to a trial or a court hearing. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Enslaved women were often forced to supervise a group of children, which may or may not include her own. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Some Patriots held negative opinions of Quakers, not because they refused to fight or take sides in the war, but because of the Quakers’ active resistance to the practice of slavery. As believers in universal human equality, many Quakers opposed slavery and took the societal disruption of the war as an opportunity to emancipate their enslaved people. Previously, British law had forbid emancipation. When the North Carolina government declared British laws void and made no mention of reinstating a ban on emancipation in the new state constitution, the Quakers seized the moment as an opportunity. Quaker meetings throughout northeastern NC urged their congregants to end the practice of slavery.

A 1779 report from the North Carolina General Assembly expressed that body’s irritation with the Quaker action, citing that freeing enslaved people was illegal—which it was not—and that the assembly needed to write a bill to establish this, so that further attempts to free enslaved individuals may be restricted.

Revolutionary War pension applications offer a unique opportunity. Pension applications allowed former soldiers to tell their stories and provide their own perspectives on interactions with Quakers during the Revolution. The four applicants listed below engaged with Quakers in North Carolina.

Illustration of a man in a North Carolina militia.

Peter Lesley

Signature of Peter Lesley, from his application for a veteran’s pension. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Peter Lesley was a private in the Randolph County Militia in 1780. Aside from the regular soldier’s duties of marching and drilling, Lesley also stated that he spent ten days “thrashing The Quakers wheat.” Wheat was on the provision tax list in 1780, and Quakers were required to pay higher taxes than other citizens. Lesley’s company collected this provision tax directly from the Quakers’ fields by harvesting wheat for themselves and for the Patriot forces at large. Lesley’s actions would have been a standard order for a private, and his story demonstrates how Patriots depended on Quaker crops to keep the army running.

William McGehe

William McGehe was a private in the Virginia State Militia. In 1780, McGehe’s company found itself in North Carolina, where they encountered a large group of Loyalists hiding in a Quaker community. McGehe didn’t offer any other comments on this incident, but his recollection of it is reflective of the common suspicion toward Quakers: Loyalists could be using the nonviolent Quakers as a convenient hiding spot—the Quakers wouldn’t have turned them in—or the Quakers could secretly be Loyalists themselves.

Signature of William McGehe, from his application for a veteran’s pension. Courtesy of the National Archives.

William Clark

Signature of John Clark, from his application for a veteran’s pension on behalf of his deceased parents, William and Eleanor Clark. Courtesy of the National Archives.

William Clark was a captain in the Randolph County Regiment of the North Carolina Militia from 1779 to 1781. He was remorseful for having taken human life in military action, and he converted to Quakerism after the Revolution. His wife Eleanor likely converted with him, and they raised their children as Quakers. Clark never applied for a veteran’s pension because of his new faith, but after he and his wife died, their youngest son, John, applied for a pension on their behalf. William’s conversion demonstrates that not all soldiers were invested in the military aspect of the war, contrary to how it may have seemed based on the public opinion of noncombatants.

Andrew Peddy

Signature of Andrew Peddy, from his affidavit of support in William Geane’s application for a veteran’s pension on behalf of his deceased parents, Philip and Mourning Geane. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Peddy was visiting a Quaker acquaintance near Lindley’s Mill when the battle occurred. He reported that after the altercation, the Quakers of the community collected and buried the dead, including Philip Geane, and cared for the wounded Patriots and Loyalists left on the field. Caring for the wounded in wartime has since become a hallmark of Quakers, but this instance illustrates the beginnings of the tradition and one of the major ways Quakers contributed to the war effort without fighting.

Philip Geane was a private in the Chatham County Militia in 1781. He died at the Battle of Lindley’s Mill. A neighbor, Andrew Peddy, witnessed how a community of Quakers interacted with Geane’s company.

Quakers cared for wounded soldiers abandoned on battlefields.

This painting, The Presence in the Midst by James Doyle Penrose, depicts a a scene of divine intervention during a colonial Quaker meeting.

The end of the war brought some changes to the legal relationship between the state and Quakers. The North Carolina General Assembly allowed Quakers to affirm their fidelity to the state instead of swearing an oath of allegiance, enabling Quakers to attain citizenship and claim property through alternative means. Quakers still faced increased property and provision taxes in lieu of military service, though the state put limits on how much a Quaker could be taxed.

Quakers continued to clash with the state government over the question of slavery. The Eastern Quarter of Quakers petitioned the Assembly in 1782, stating that enslaved people should be freed and that the practice of slavery was a direct contradiction to the ideals outlined in the Declaration of Independence. When the Assembly met the following month, their decision was swift and much to the Quakers’ dismay. The Assembly decided that freeing slaves would set a dangerous precedent for the community, and rejected the petition.3

This painting, Georges et Elisa Chez les Quakers, depicts a scene from Uncle Tom's Cabin, a popular abolitionist novel written by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Quakers were renowned for their abolitionist efforts, including opening their homes for use on the Underground Railroad. Courtesy of Swarthmore College.

Travelers on the Great Wagon Road, Western Piedmont. Quakers may have used a similar wagoned caravan to migrate from North Carolina.

In the early 1800s, many Quakers decided they had had enough. They were financially devastated after years of exponentially rising taxes. They were emotionally pained by the state’s greed in its refusal to recognize enslaved individuals as people. They had been consistently discriminated against as a religious minority for practicing what they preached, despite living in a state that was supposed to be religiously tolerant. The American Revolution had undeniably taken its toll on the Quakers of North Carolina, and so many chose to leave. After years of oppression, many Quakers left North Carolina, finding peace and new communities in Indiana.4

- The impacts of the War of Regulation and the American Revolution are significant and more deeply explored in Steven Jay White, "North Carolina Quakers in the Era of the American Revolution," Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1981.

- American Quakers in and outside North Carolina experienced devastation beyond financial ruin. For more information, see Mark Pearcy, "'We Are Your Real Friends': The Exile of Quakers During the American Revolution and Teaching Contentious Issues," Ohio Social Studies Review 55, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 36-46.

- The Quakers' abolitionist efforts extend far beyond what has been discussed in this exhibit. For more information, see Michael J. Crawford, The Having of Negroes is Become a Burden: The Quaker Struggle to Free Slaves in Revolutionary North Carolina (Gainesville: University Press of Florida: 2010).

- For more information on American Quakers and American Quakerism generally, see Arthur J. Mekeel, "The Relation of the Quakers to the American Revolution," Quaker History 65, no. 1 (Spring 1976): 3-18; Neva Jean Specht, "'Being a Peaceable Man, I have Suffered Much Persecution': The American Revolution and Its Effects on Quaker Religious Identity," Quaker History 99, no. 2 (Fall 2010): 37-48.

- The painting of a Quaker meeting used in the icon and banner headings for this exhibit is credited to the Library of the Society of Friends: Library of the Society of Friends Catalogue | Details (Accessed 11 July 2025).

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1)_0_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1)_1.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)