North Carolina Women and the War of Regulation

A collection of documents outlining North Carolina women's experiences during and contributions to the War of Regulation in 1771.

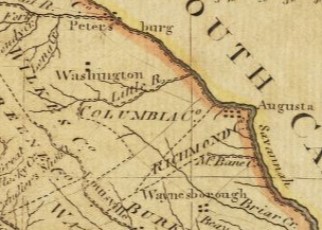

In the mid-18th century, disgruntled colonists in North Carolina’s backcountry, called Regulators, challenged what they viewed as a corrupt government. By the time the rebellion ended in 1771, the unrest had impacted thousands of North Carolinians from many diverse backgrounds. Yet, women’s influence on the war remained understudied. By exploring documents like receipts, petitions, and military orders, we can uncover how women shaped this important chapter in both North Carolina and American history.

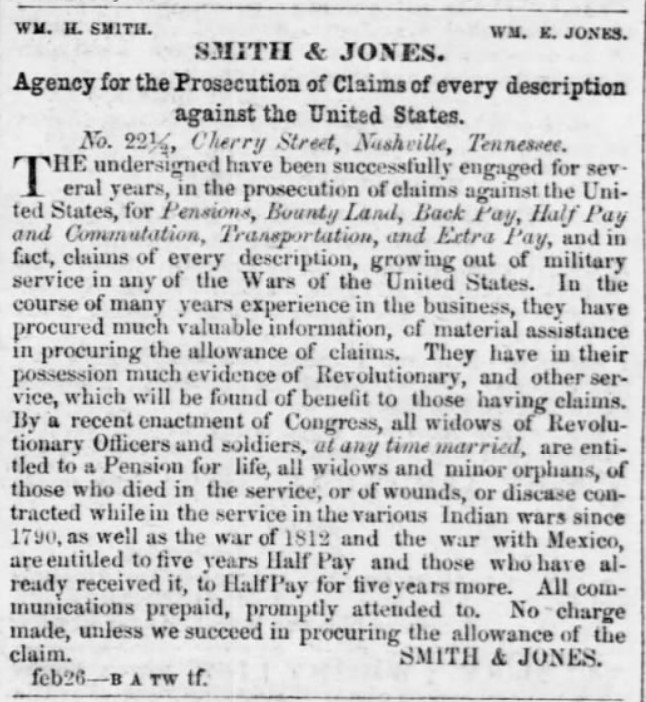

An engraving of women doing domestic tasks. Several craftswomen used their skills to support the militia and earn money during the War of Regulation. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Identified

Transcribed

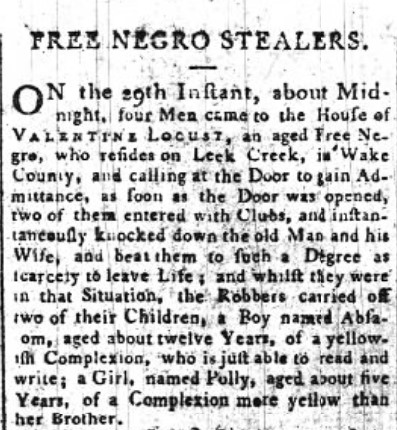

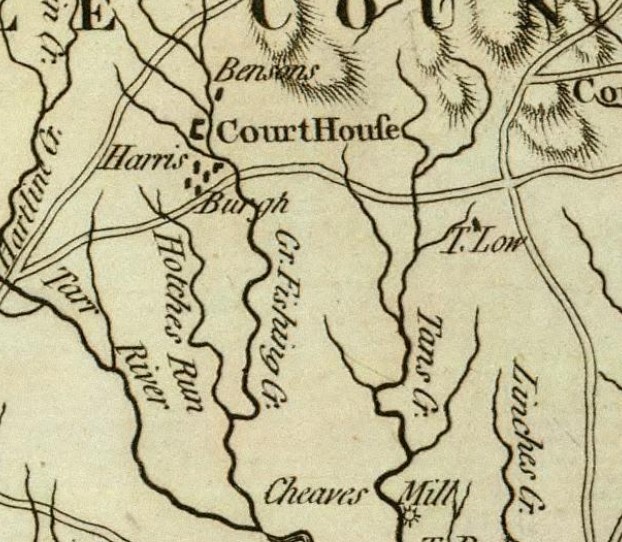

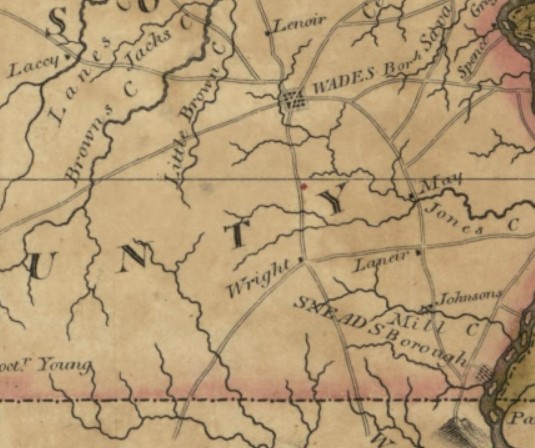

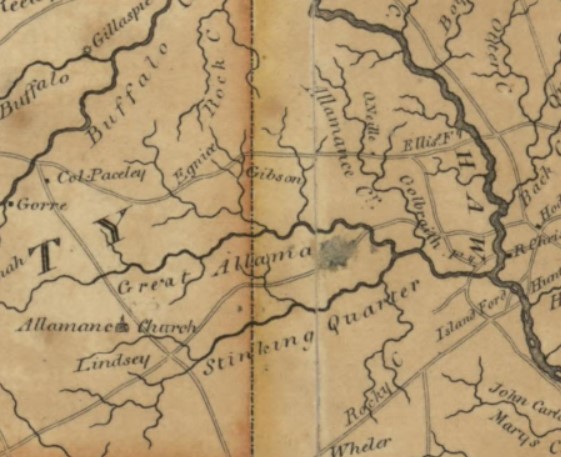

In 1765 the Regulators began petitioning against unfair taxation, exploitative government officials, and a convoluted land grant system. As years went by with no meaningful reform by colonial officials, the Regulators’ frustrations mounted. By September 1770 the Regulators had enough and turned to illegal tactics. In an event called the Hillsborough Riot, a group of them disrupted the District Superior Court and attacked multiple government officials. In response, in March 1771 Governor William Tryon assembled a militia to combat the growing violence. Two months later on 16 May 1771, the colonial militia defeated the Regulators at the Battle of Alamance. Afterward, Regulators and sympathizers who survived had to swear loyalty to the royal government. Though the War for Regulation is a well-known era in North Carolina history, the role women played in shaping these events remains relatively unknown.1

An engraving titled “Governor Tryon and the Regulators. Courtesy of the Bruce Cotten Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library at UNC Chapel Hill.

Keep scrolling to uncover the forgotten stories of women and the War of Regulation.

In March 1771, several North Carolina women aided in the raising of the militia as a way to earn money.

Wealthy women contributed to the militia by lending out their assets. Mary Conway was a wealthy widow who provided housing for the Craven County Regiment in New Bern. By giving the soldiers a more secure location to stay, Conway made a profit and influenced the war. Aside from property, other women like Mrs. Vail also contributed to the war effort through the practice of hiring out enslaved people to the militia. Though it is unclear in what capacity the person Mrs. Vail enslaved worked with the militia, there were many enslaved craftspeople in New Bern including carpenters, blacksmiths, saddlers, and tailors. It is also possible this enslaved person completed domestic tasks for the militia such as cooking and washing clothes.2

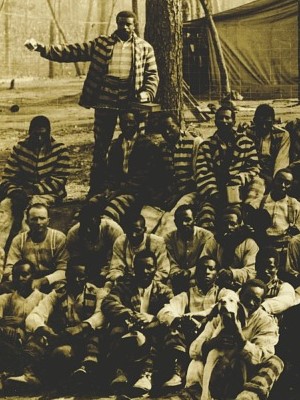

A nineteenth-century engraving of free Black craftspeople at work. The enslaved individual who was hired out to the militia may have worked in a blacksmith wheelwright shop like those depicted in this image. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

An engraving of a woman sewing. Needlewomen played an integral part in the raising of the North Carolina militia. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Women also supported the militia with skills like sewing. Anne Walker made 60 haversacks, enough to outfit an entire regiment. Mrs. Moore sewed canvas which was likely used to make shelters for the militia’s expedition across North Carolina. Colonial militia records also contain many receipts for sewing materials. While these documents contain no direct references to women, it is likely that needlewomen like Anne Walker and Mrs. Moore used these items to create equipment essential for the militia’s expedition.3

An illustration of a soldier with a shot bag. Militiamen used shot bags to hold musket balls, powder, and other materials needed for loading and firing their weapons. Women were likely hired to make these bags for the militia. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, World Digital Library.

A hat with a recreation cockade. Because militiamen were not given uniforms, cockades were attached to their hats to differentiate themselves from the Regulators. Women were likely hired to make the cockades. Courtesy of Alamance Battleground.

While the women listed above made the choice to support the militia, others were forced to. On 8 May 1771 the militia seized Elizabeth Stroud’s horse as they made their march through Hillsborough. Countless other women also had their livestock, crops, or property seized for the militia’s use throughout the course of the war. Although the militia promised to compensate these citizens eventually, these promises weren't always kept.

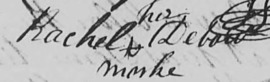

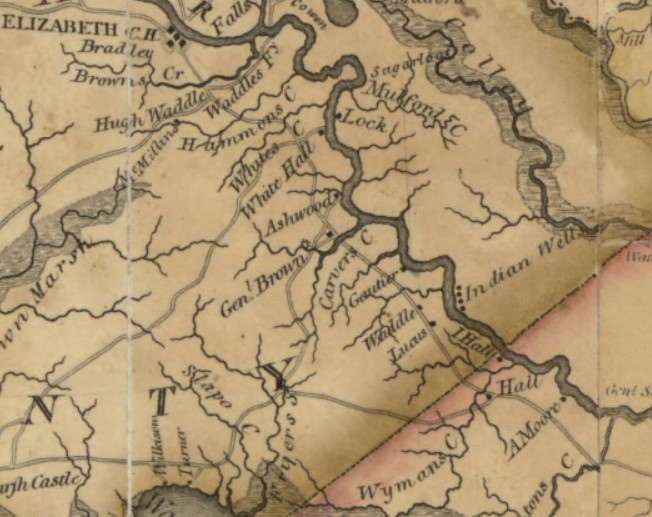

In April 1771 the militia set out on their expedition across North Carolina to quell the Regulators.

At some point during the militia's journey, General Hugh Waddell hired several washerwomen. These women might have been relatives of soldiers who followed them on their march or women local to the encampment. Laundresses helped keep the camps clean and prevent the spread of disease. This was an integral job for any military expedition – a fact many women used to their advantage by charging the highest rates possible for their services.4

A nineteenth-century engraving of women working in an encampment. Laundresses who worked for the militia would have used similar techniques to those pictured, such as line drying. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

At the Battle of Alamance an estimated 1,000 militiamen faced off against 2,000 Regulators. Despite being outnumbered, the militia was able to defeat the Regulators because of its artillery of two light field guns and six swivel guns.

A recreation light field gun like those used during the battle of Alamance. Courtesy of Alamance Battleground.

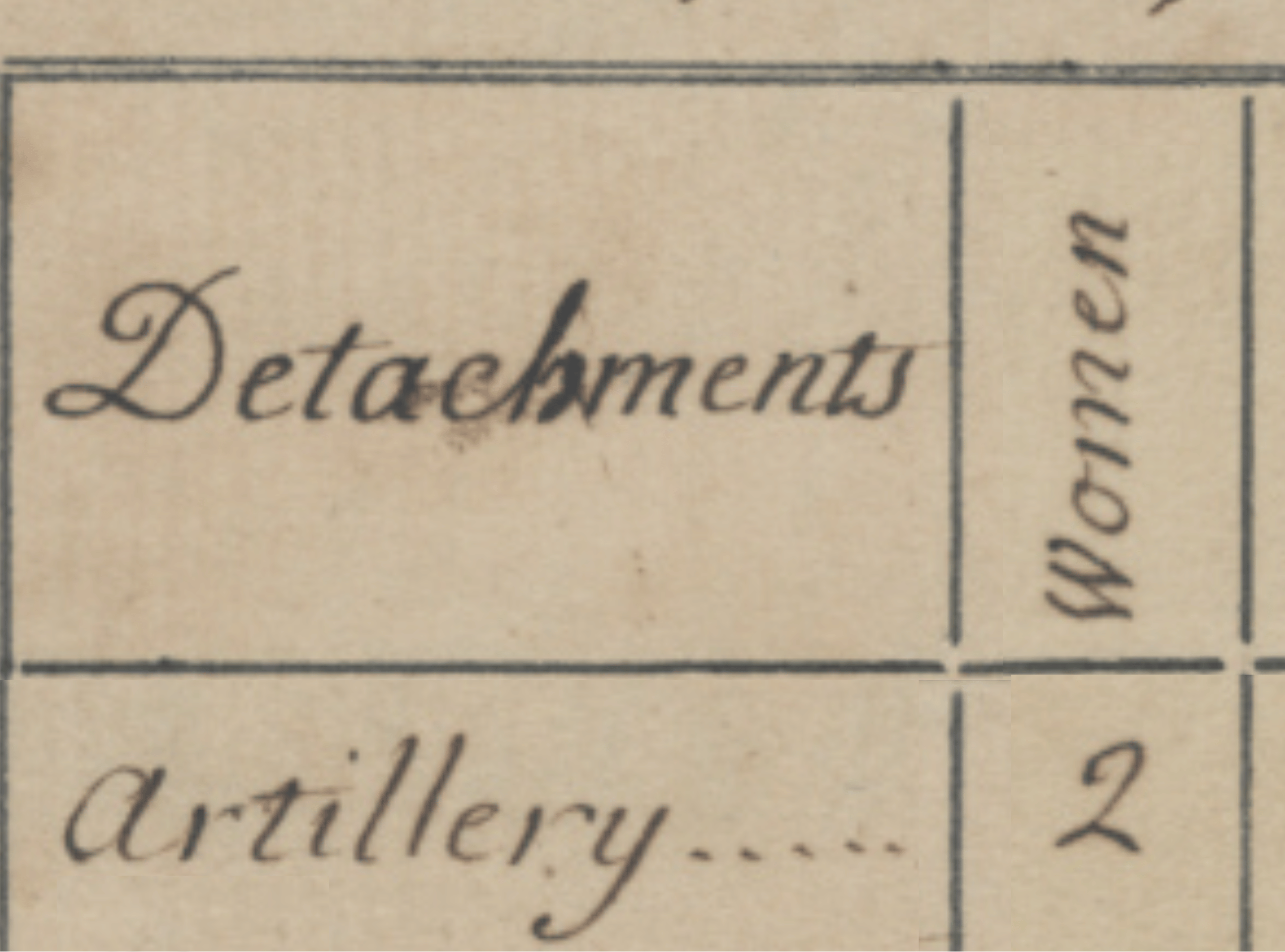

An edited excerpt of the Chart of Returns of the North Carolina Militia, 22 May 1771. This document indicates that two women were assigned to the artillery detachment of the militia.

A chart of the militia written shortly after the battle lists how many officers and soldiers manned the artillery during battle. This document notes two women in the artillery. While they may have been laundresses, the fact that other units were known to have washerwomen that are not enumerated in this report indicates that the women associated with the artillery had a different function. It is possible these women assisted with the operation of the artillery during the battle.

One task the artillery often relied on women for was water carrying. After firing a cannon, the gun crew cleaned out the barrel with water to extinguish remaining sparks and clear out unexploded powder. Over the course of multiple cannon firings, women would gather water from nearby creeks, freeing male soldiers to work the guns. While some women worked with gun crews to support their relatives in the militia, others did so to ensure they received rations.5

An engraving of a woman collecting water. There were several creeks and streams near where the Battle of Alamance took place that women might have used to collect water for the artillery. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

After the battle, women served an important role in caring for the wounded.

While the exact count of those wounded during battle are unknown, it is clear a significant number of individuals were injured. After the fighting ended, Tryon ordered that all the wounded—both militia and Regulators—should receive medical treatment. In addition to the male doctors the militia hired, female camp followers also would have done what they could to treat the injured. When the militia began their journey home two days later, Tryon ordered for the sick and wounded to move to the nearby home of a captain. The same order also authorized officers to hire nurses and pay them with fresh provisions. By serving as nurses, women helped minimize suffering and death for both sides.6

An engraving of a man and woman tending to an injured man. Women were hired as nurses to assist male doctors in treating the sick and wounded after the Battle of Alamance. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The Militia

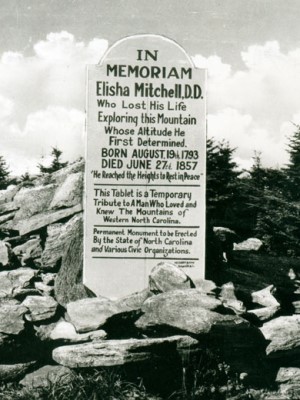

In late 1771 several women whose relatives had died while serving in the militia petitioned the government for financial assistance to support themselves and their families. Documentary evidence shows that at least six women were able to secure pensions. Their names were Anne Bryan, Anne Ferguson, Elizabeth Harper, Faithy Smith, Fearnaught Beasley, and Elizabeth Strange. Some of the women who received pensions were already well off, despite claims in their petitions that their relative’s deaths had left them destitute. For example, Fearnaught Beasley was awarded ten pounds per year following her son’s death. However, based on land grants and deeds it is clear Beasley was an extremely wealthy woman.7

An engraving of a woman with several children. Many women were left to support themselves and their children after their husbands died while serving in the militia. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

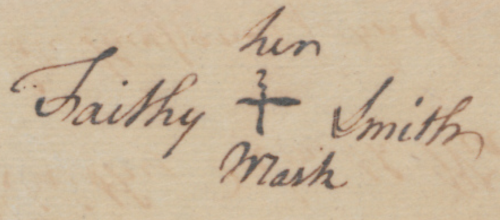

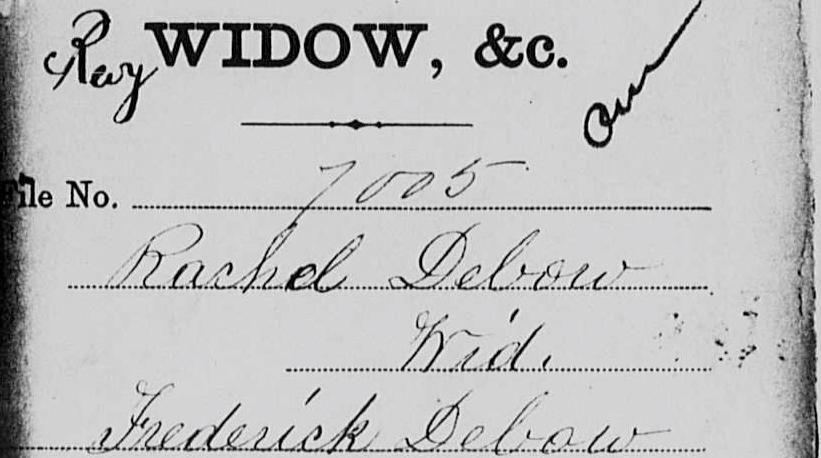

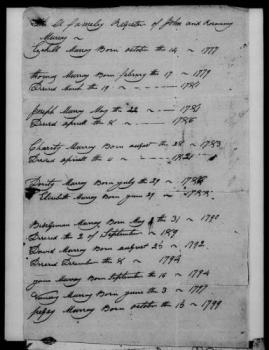

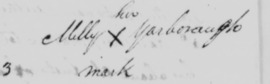

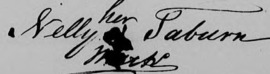

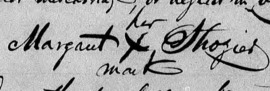

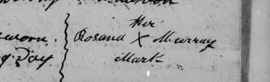

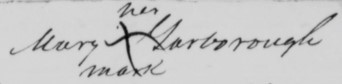

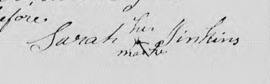

Faithy Smith's signature mark from her petition.

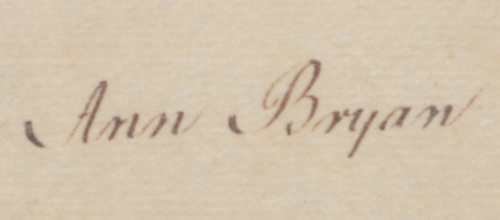

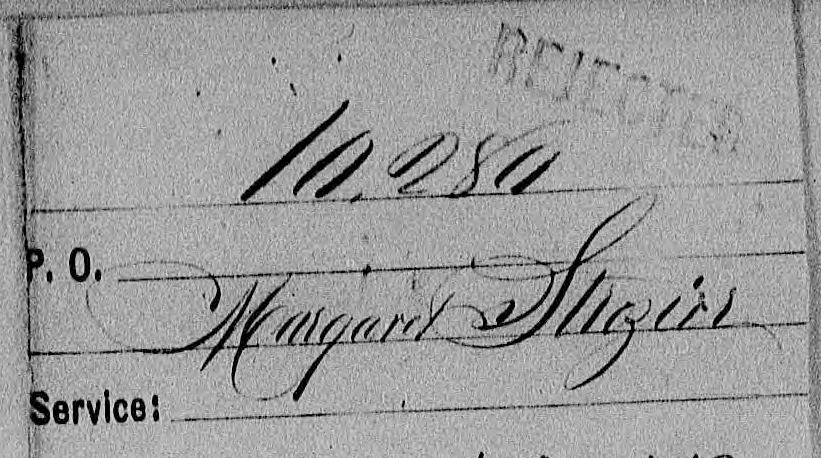

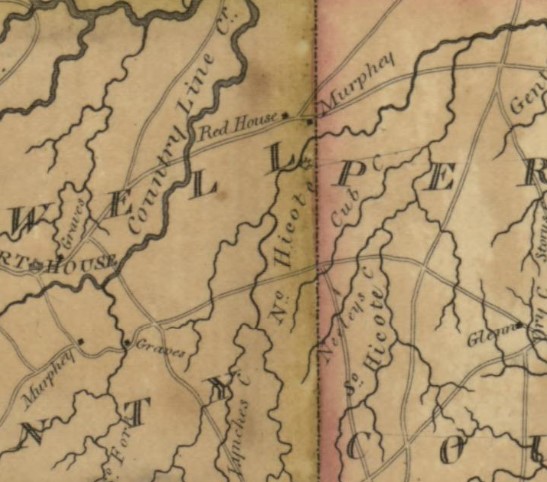

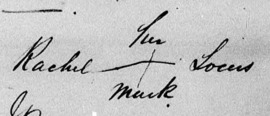

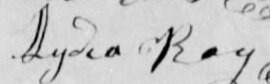

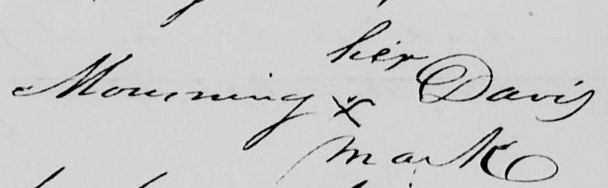

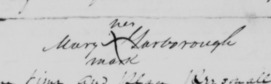

Anne Bryan's signature from her petition.

Many women persuaded the government to grant them pensions by referencing their children. In her petition, Faithy Smith claimed that without the legislature’s help, her infant would have “no kind of support” due to her husband’s death. Anne Bryan similarly described her six small children as in “distressed circumstances”. This proved an effective tactic: the resolution to grant Anne Bryan, Anne Ferguson, Elizabeth Harper, & Faithy Smith pensions referenced the “small children who, by the loss of their Fathers must without the Assistance of the Public be reduced to extreme want.”

The Regulators

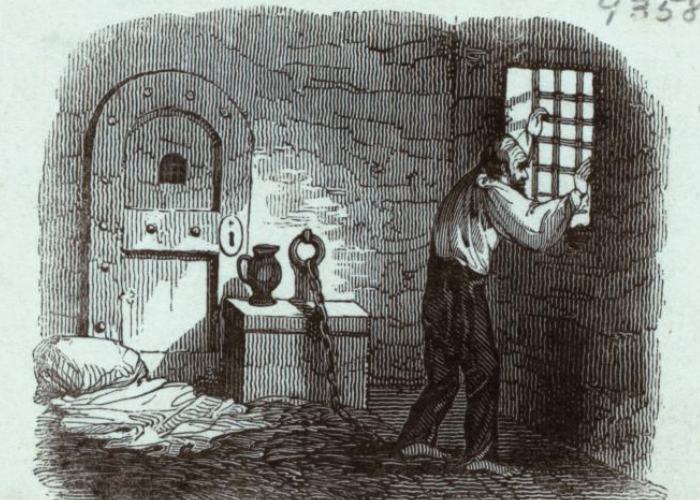

Mothers and wives of militiamen were not the only ones impacted by loss during the War of Regulation. Women from pro-Regulator families also featured prominently in post-war legislative petitions. As the Regulators faced punishment for their actions, many local citizens petitioned the government to secure pardons on the agitators' behalves. Citizens sympathetic to the Regulators could not ask the legislature to absolve the movement’s leaders of their crimes, so they instead appealed to the legislators’ sense of honor, asking them to think of the women and children and how they would be impacted by a man’s imprisonment or execution.

An engraving of a man looking through a prison cell window. Many men were arrested, and even executed, for committing treason throughout the Regulator Rebellion. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

An engraving of two women. Petitioners persuaded government officials to pardon Regulators by alluding to the agitator's female relatives. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

In March of 1771 Elizabeth Fruit’s husband, John Fruit, was tried for violating the Johnston Riot Act, a crime which was punishable by death. Later that year, 127 North Carolinians petitioned for John Fruits’ pardon. They alluded to the impact his execution would have on Elizabeth and their children, stating, “we also further Humbly shew that the said John Fruit hath a wife and sundry small Children who are in the utmost Distress, for want of that Comfort and support which he as a Father and Husband ought to supply them with.” In late 1771 Mary Hunter’s husband James was wanted for treason because he had been a leader in the Regulator movement. A petition from several prominent Guilford County citizens called for Hunter’s pardon. Instead of claiming Hunter was innocent, petitioners alluded to how his outlaw status impacted his wife, his mother-in-law, Mary Ann Walker, and his children. The petitioners stated, “We Begg his Life for the sake of a poar disconslet Wife and Small Children and an aged mother Wo has no other Man in the Life and his affectioned Relations With Whom We Sympathise.”

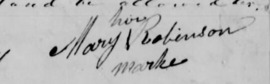

In addition to petitions, women also helped secure pardons for Regulators by providing alibis. John Pugh was a prominent Regulator leader. Due to his position amongst the Regulators, he became a target for retribution and was charged with violating the Johnston Riot Act. In addition to a petition that referenced his wife and small child, several depositions also attempted to clear John Pugh’s name. Elizabeth Jones (the wife of a Regulator sympathizer), Elizabeth Pugh (John Pugh’s mother), and Peninah Walker (John Pugh’s sister), all claimed they saw him a few days after the Hillsborough Riot in another part of the state. A woman named Ann Jones, who may be related to Elizabeth Jones, stated she saw John Pugh the day before the riot and a few days after somewhere 40 miles away from Hillsborough. Catherine Marley, a Guilford County resident, gave the most detailed alibi for John Pugh. She vowed that she also saw John two days after the riot around two p.m. and that he asked her if she had heard any news.8

A print of Tryon Palace. All of the women's petitions and depositions were sent to Tryon Palace to be processed by the North Carolina Colonial Assembly. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

- The Regulator Rebellion is a complex period in both North Carolinian and American history. For more information on the events of the Regulator Rebellion, see Marjoleine Kars, Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina (The University of North Carolina Press: 2003); Carole Watterson Troxler, Farming Dissenters: The Regulator Movement in Piedmont North Carolina (Raleigh: Office of Archives and History, 2011).

- For more information about Black craftspeople in New Bern, see Catherine W. Bishir, Crafting Lives: African American Artisans in New Bern, North Carolina, 1770-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

- During the general muster of the militia, Governor Tryon ordered that each man in the militia be given, “a pair of Leggings, a Cockade and a Haversack.” Women like Ann Walker would have been hired to make these materials for each of the estimated thousand individuals who enlisted in the militia. Circular letter from William Tryon to North Carolina Militia Officers, 19 March 1771, CO 5/314, National Archives of the United Kingdom. For more information about how canvas was used to create shelters in colonial America, see Zelma Bendure and Gladys Pfeiffer, America’s Fabrics: Origin and History, Manufacture, Characteristics and Uses (New York: Arno Press, 1972).

- The militia relied on washerwomen to prevent the spread of disease through cleaning. Washerwomens’ roles were so important that they received rations and pay. They were also held to the same standard as soldiers—their work was directly overseen by the militia and they were required to march alongside the soldiers, carrying their own supplies. For more information about camp followers see Holly A. Mayer, Belonging to the Army: Camp Followers and Community during the American Revolution (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1999); “Forgotten Revolutionaries: Camp Followers Discovery Cart,” Museum of the American Revolution, May 9, 2020, https://www.amrevmuseum.org/forgotten-revolutionaries-camp-followers-discovery-cart

- Women working with the artillery during the 18th century was a relatively common phenomenon. Scholars estimate that thousands of women served with gun crews in the American Revolution. The job of water carrier was often assigned to women who needed a way to earn rations while accompanying a relative who served in the artillery on their expedition. While it is likely the women listed in the Chart of Returns of the North Carolina Militia, 22 May 1771 worked as water carriers, it is impossible to be completely certain due to lack of documentation. This is a common problem for historians as, “the routine activities of water carriers or common gunners are not apt to be reported to senior officers or even written home about.” For more about women who served in gun crews in the 18th century, see Linda Grant De Pauw, “Women in Combat: The Revolutionary War Experience,” Armed Forces & Society 7, no. 2 (Winter 1981): 209–26; Emily J. Teipe, “Will the Real Molly Pitcher Please Stand Up?,” Prologue 31, no. 2 (Summer 1999).

- In the 18th century, women were responsible for caring for sick family and community members. Women often learned about medical treatments and even medicine recipes from older female relatives. While formally trained male doctors were hired by the militia for surgeries and treating high ranking official, female nurses were responsible for administering medications and seeing to the hygiene of the sick. It is possible that the nurses hired by Governor Tryon were the relatives of army officers or “public” local women. For more about 18th century women and medicine, see John C. Kirchgessner, “Nursing in the Colonial Era and Early Days of the United States 1607–1840,” essay, in History of Professional Nursing in the United States: Toward a Culture of Health (New York: Springer Publishing, 2017), 23–44; Barbara Ehrenreich, Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (New York: The Feminist Press, 2010); Jeanne E. Abrams, Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

- Fearnaught Beasley was made the executor of her husband’s estate in 1759. His will states that he owned at least two plantations and 300 acres of land. In 1766 Fearnaught acquired an additional 174 acres of land in Craven County. Based on this evidence, it is clear she was an incredibly wealthy woman despite the claims she makes in her pension application. Craven County Land Grant File 2723, 26 September 1766, Land Patent Book Vol. 18, pg. 315, Land Grant Microfilm Collection, State Archives of North Carolina; Will of Simon Beasley, 1759, Craven County Original Wills and Estate Papers, State Archives of North Carolina.

- For more about the consequences of the Regulator Rebellion, see Kars, Breaking Loose Together, 206-214; Troxler, Farming Dissenters, 117-124.

The illustration of women completing domestic tasks used in icon for this exhibit as well as other engravings credited to the New York Public Library are from the Alexander Anderson Scrapbooks, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/alexander-anderson-scrapbooks#/?tab=navigation (Accessed 19 July 2024).

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)