The Story Lives On: The Legacy of North Carolina's Incarcerated Railroad Workers

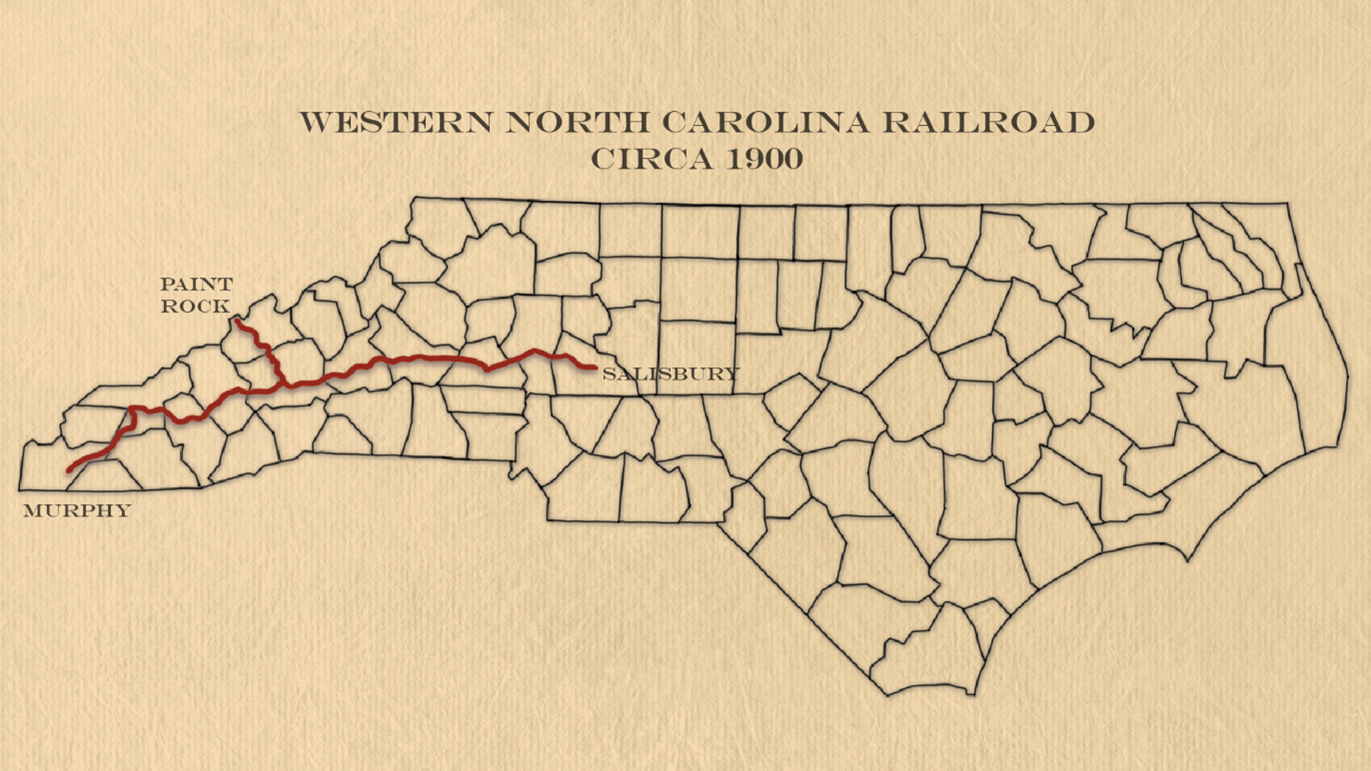

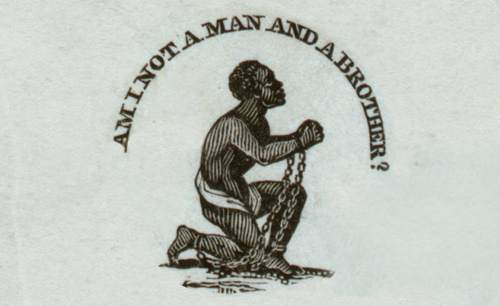

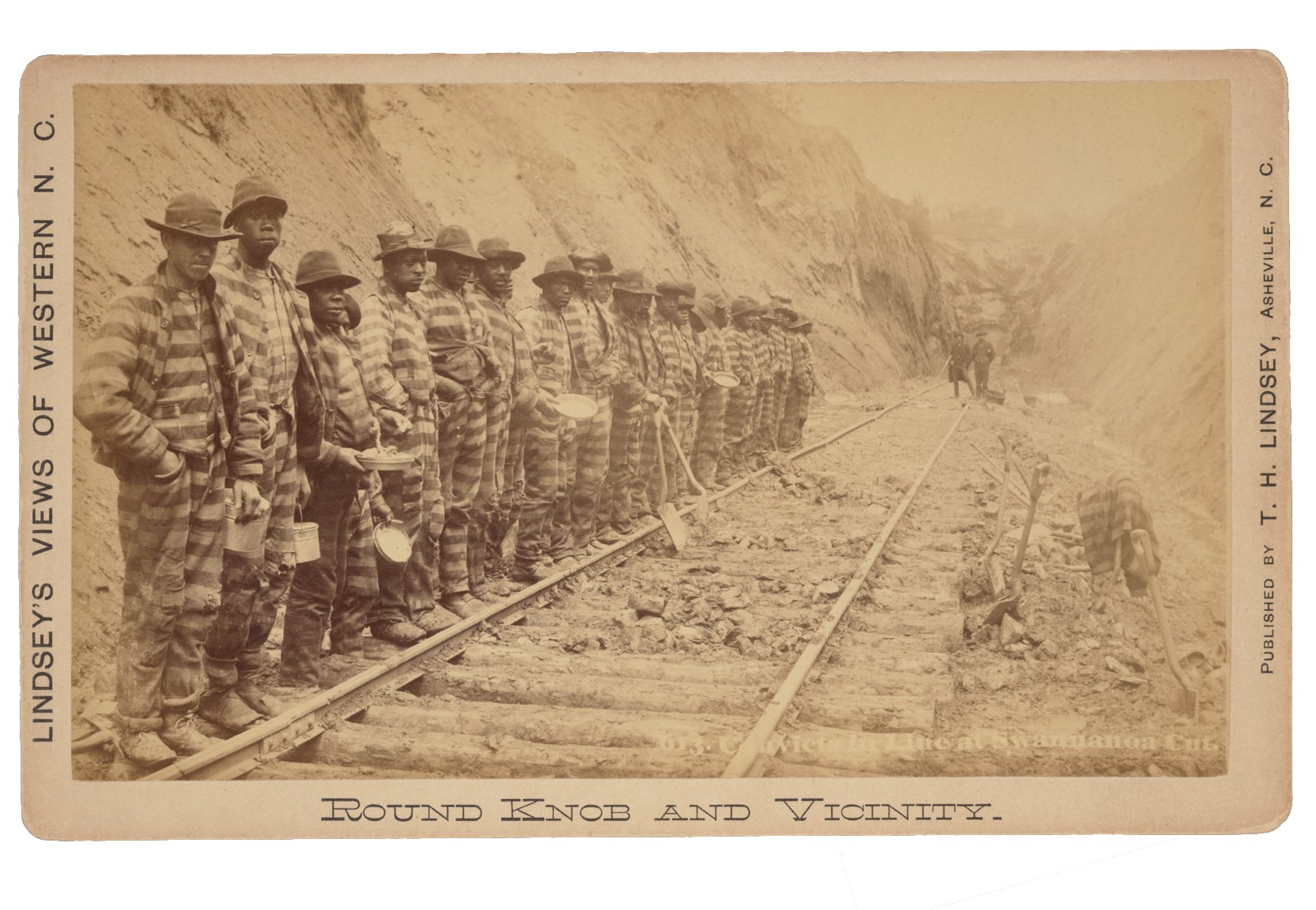

The Western North Carolina Railroad had a major impact on North Carolina history. Today, scholars and activists are emphasizing incarcerated laborers’ role in building this vital infrastructure. Though the system of forced labor used on the Western North Carolina Railroad, convict leasing, was phased out during the early twentieth century, incarcerated people continue to experience harsh labor conditions in the modern era.

Two undergraduate students from Western Carolina University search for artifacts during excavations at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp on the former Western North Carolina Railroad in 2024. Photo by Ashley Evans.

Impact on the Region

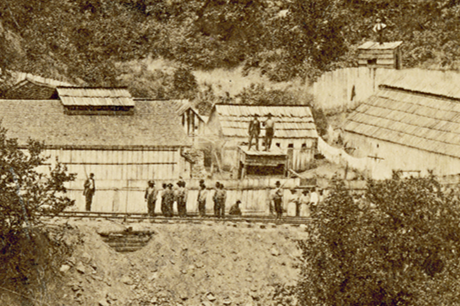

The railroad helped transform western North Carolina. Between 1870 and 1900, the population of Asheville swelled from 1,400 to nearly 21,000 people. Beginning with the operation of the rail lines to Asheville in 1880, passengers and goods moved through the region more quickly than ever before. The railroad facilitated the logging industry and the growth of manufacturing in western North Carolina.

Today, tourists flock to Western North Carolina to experience the beautiful vistas; however, few realize that the roads and rails they’re travelling on through mountain passes were built on the backs of incarcerated laborers nearly 150 years ago.

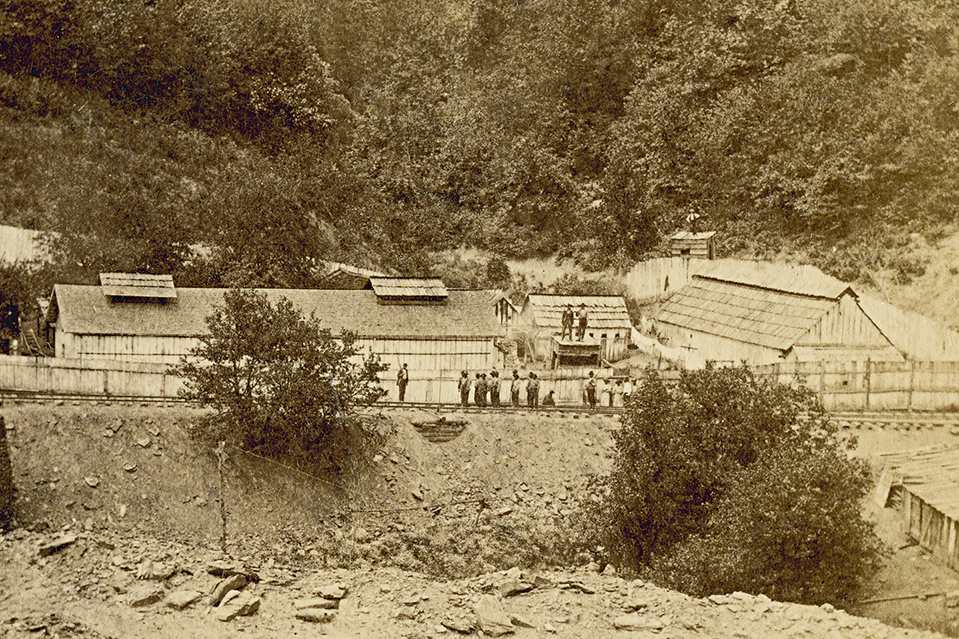

Tourists from around the country came to western North Carolina for sightseeing, utilizing the railways incarcerated laborers built to see sites like Round Knob in McDowell County. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

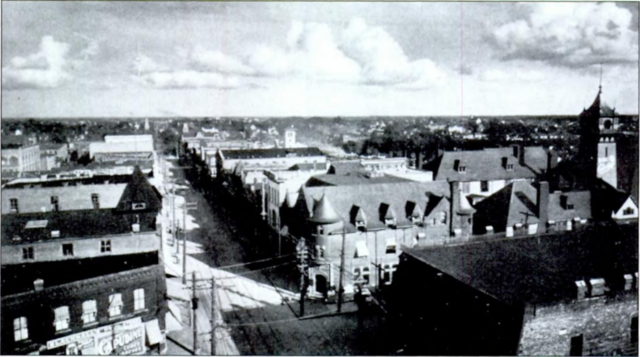

Asheville, photographed here in 1902, grew into a bustling metropolis due to the railroad. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Memorials to the Incarcerated Railroad Laborers

In 2020, Dr. Daniel Pierce and Marion Mayor Steve Little founded the Railroad and Incarcerated Laborer (RAIL) Memorial Project with the goal of memorializing the imprisoned laborers who built the Western North Carolina Railroad.1 The RAIL Project brought together western North Carolina historians, archivists, museum specialists, and other community members. That same year, the Mountain Gateway Museum at Old Fort unveiled a new exhibit about the use of incarcerated labor entitled “The Price of Progress.” The RAIL Project erected the “Memorial to the Incarcerated Railroad Workers Who Built the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad” near the local landmark of Andrew’s Geyser on the outskirts of Old Fort, in 2021. The group commissioned two multi-generational African American stonemasons from the area, Paul Twitty and Jimmy Logan, to build the monument.2

The ”Memorial to the Incarcerated Railroad Workers Who Built the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad” just outside Old Fort. Commissioned by the RAIL Project. Photo by Cayla Colclasure.

The North Carolina Highway Marker Program unveiled a marker in 2024 which commemorates the in carcerated laborers who built the Western North Carolina Railroad, and particularly those that died in the Cowee Tunnel Disaster of 1882.

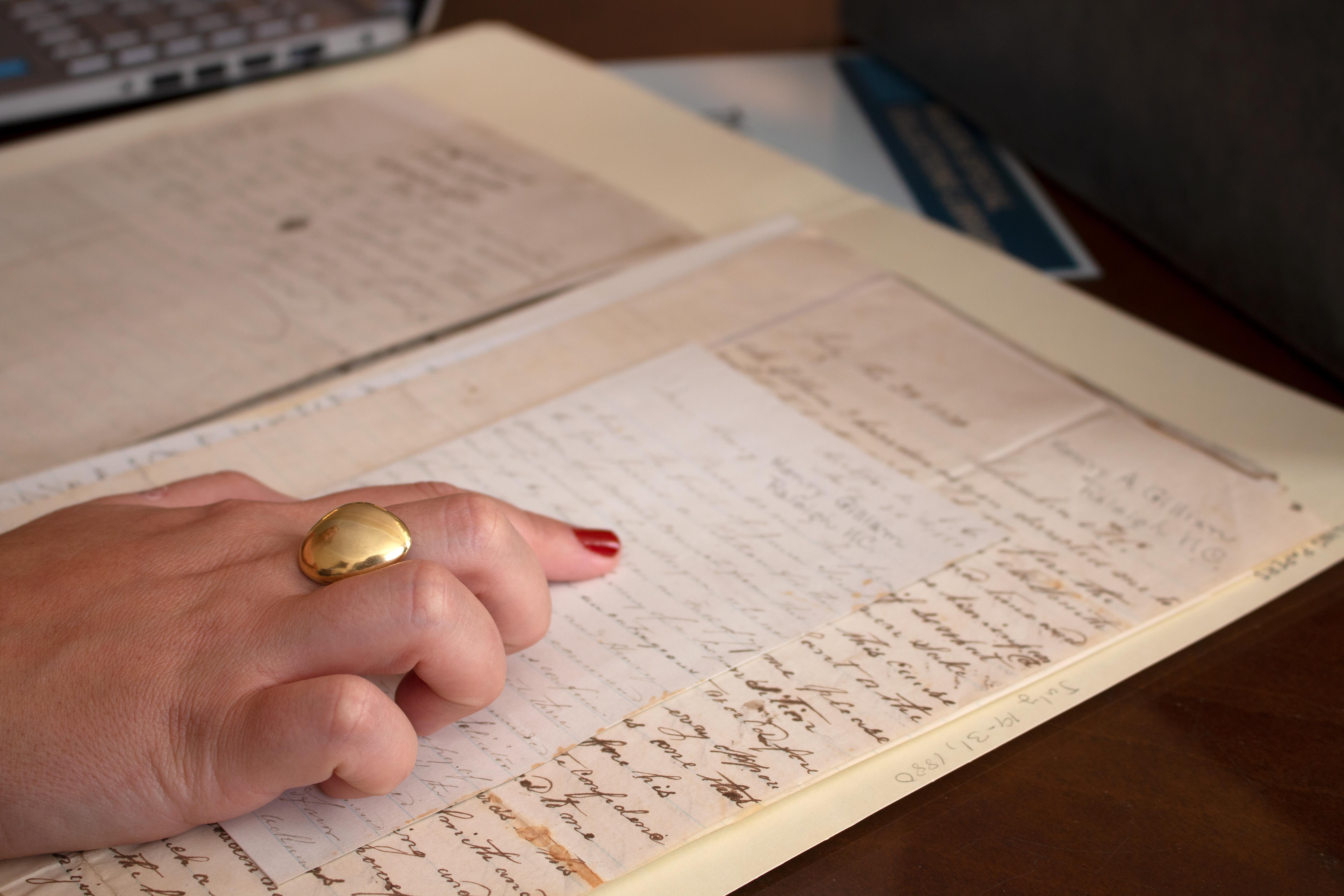

Dedicated in 2024, the Incarcerated Laborers State Historic Highway Marker commemorates the prisoners who built the Cowee Tunnel and lost their lives in the process. The Jackson County chapter of the NAACP applied for the marker and worked with the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources to create the text.3 Also in Jackson County, at Western Carolina University, a temporary exhibit entitled “Shadows of Incarceration: the Cowee 19 Story” was guest-curated by Danielle Duffy at the Mountain Heritage Center. This exhibit explored the lives of the men and boys who drowned in the Tuckasegee River on December 30, 1882, and put their stories into broader context. Duffy commissioned local artist, author, and African American memory keeper Ann Miller Woodford to do a painting for the exhibit based on the event.4

Archaeology at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp

Since 2024, historical archaeologist Cayla Colclasure has been doing archaeological excavations at the site of a Western North Carolina Railroad prison labor camp near the Cowee Tunnel. Workers stayed there while building the tunnel, including those who died in the December 1882 disaster. Artifacts from 2024 excavations were displayed as part of the “Shadows of Incarceration” exhibit, and WCU and the Jackson County Public library hosted public talks on the excavations’ discoveries. Excavations will continue in summer 2025.

Cayla Colclasure, PhD Candidate at UNC-CH, and Dr. Benjamin Steere, Professor of Anthropology at WCU, during excavations at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp. Photo by Ashley Evans.

Undergraduate students from Western Carolina University search for artifacts during excavations at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp. Photo by Ashley Evans.

Artifacts found at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp, including rusted 19th century nails from camp buildings and a ceramic Prosser button, likely from a prisoner's uniform. Photo by Cayla Colclasure.

Some of the hundreds of 19th century nails from camp buildings discovered at the Cowee Tunnel Prison Labor Camp. Photo by Cayla Colclasure.

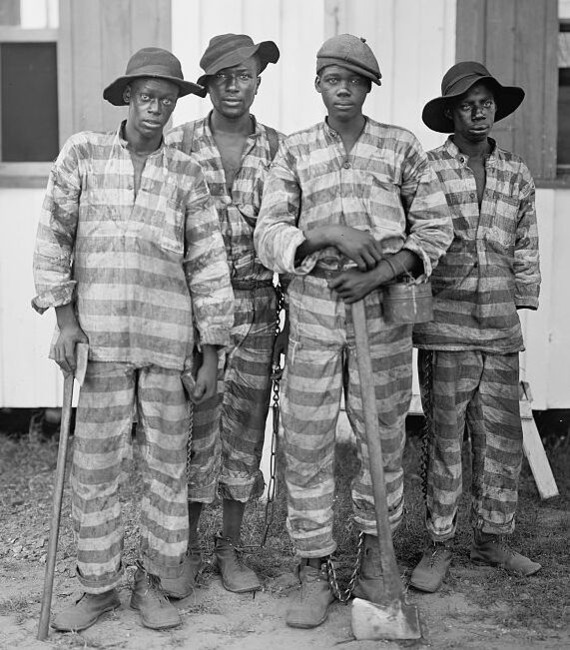

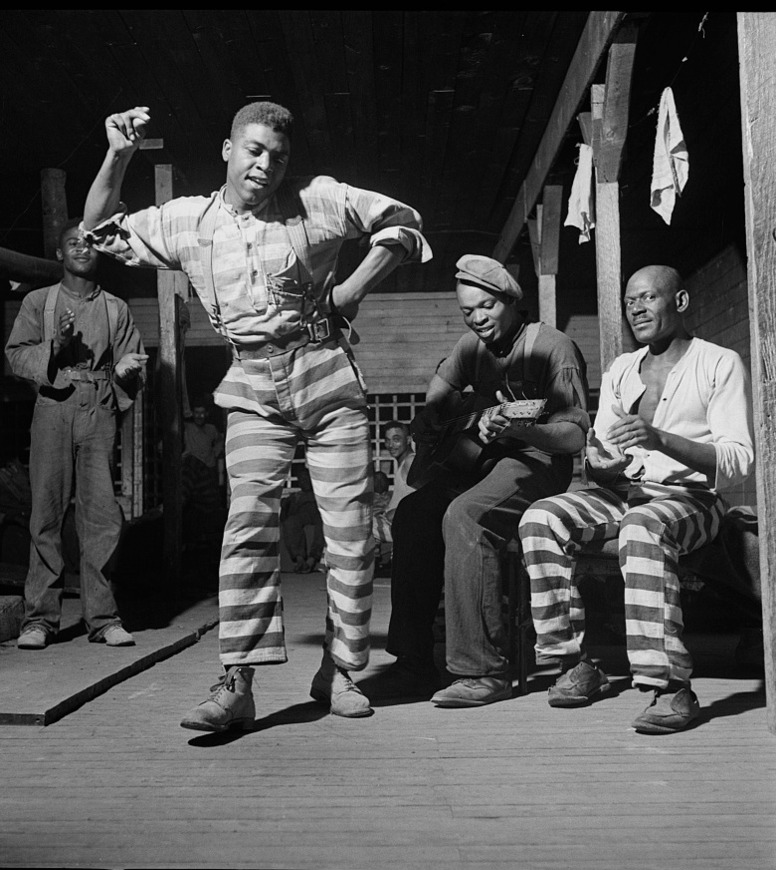

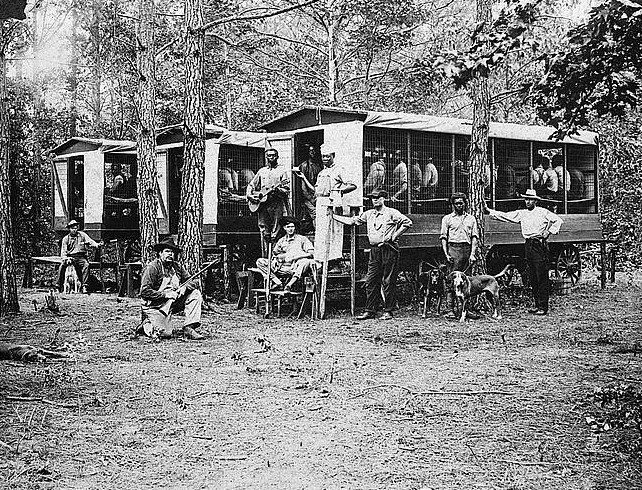

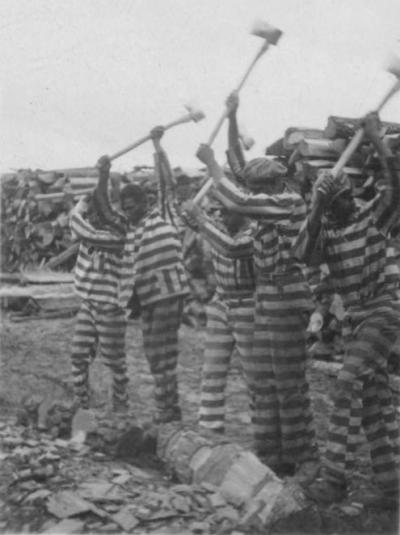

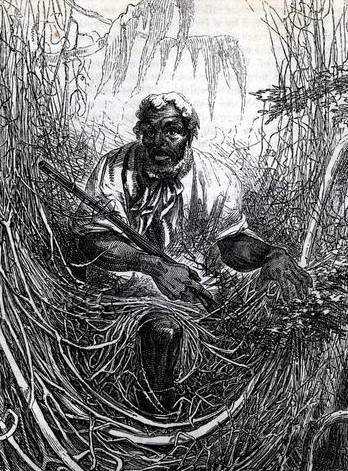

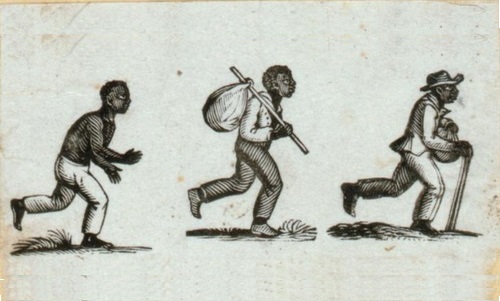

Although the western North Carolina Railroad was completed in the 1890s and North Carolina phased out the convict leasing system in the early twentieth century, the state carries on a legacy of mass incarceration into the modern era. During the early to mid-twentieth century, the state used chain gangs of convicts to build and repair roads throughout the state, following a similar system that the railroad companies had used. Throughout the 20th century prisoners performed all sorts of tasks for the state, from growing and canning food to making license plates.5

"A North Carolina Convict Camp" in Lauringburg, 1910. Five men in the front row hold dogs trained to track runaways. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Incarcerated men processing canned food in a prison labor camp in Caswell, 1945. Courtesy of North Carolina Museum of History.

The 1970s marked the beginning of the “mass incarceration” era in the United States. The dramatic rise in the number of people being imprisoned during this era is tied to economic policies which relocated manufacturing industries to countries in Latin America and Asia and left many working-class Americans unemployed. Today, the United States incarcerates a higher percentage of its population that any other wealthy nation. People of color, especially Black, Indigenous, and Latino people, continue to disproportionately face imprisonment in the U.S. According to census data, African Americans comprise approximately 13.7% of the U.S. population as of July 2021, while 38.7% of inmates in the federal prison system today are Black.6

Incarcerated people today still face abusive labor conditions across the United States. In 2023, prisoners sued the state of Alabama for working conditions they likened to “a form of slavery.” Today, incarcerated people mainly work within the prison itself, though states like Alabama still lease workers to private businesses, and in California prisoners fight wildfires.7 To learn more about incarcerated labor today, check out the resources linked below.

Further Reading:

James Faucette, Didge Daniels, and Kai Fenty, "Paying NC's Imprisoned People."

Kimber Heinz, "Stories from the Inside: Four Eras of North Carolina Prison History."

Prison Policy Initiative. "Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2025."

The Sentencing Project. "Growth in Mass Incarceration."

The Vera Institute, "American History, Race, and Prison."

Sign for Central Prison in Raleigh, North Carolina. It reads "Central Prison 1300 Western Blvd." Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- The RAIL Project.

- Paul Twitty, interview by Cayla Colclasure, Catawba Vale Collaborative, 2023.

- Leslie Leonard, "Incarcerated Laborers Who Built Western North Carilina Railroad to be Featured on N.C. Highway Historical Marker, " North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, 2024. (Accessed 22 April 2025).

- Ann Miller Woodford, Presentation to the Western Carolina University Archaeological Field School, 2024.

- Akilah Davis, "From Plantation to Prison: How American Capitalism Still Utilizes Forced Labor," ABC 11, 2023. (Accessed 21 April 2025); Michael Hennessey, "Take a Look Inside the Prison Plant where North Carolina License Plates are Created," Fox 8, 2023. (Accessed 21 April 2025).

- Federal Bureau of Prisons, "Inmate Statistics: Race," 19 April 2025. (Accessed 22 April 2025).

- Robin McDowell and Margie Mason, "Alabama Profits off Prisoners who Work at McDonald's but Deems them too Dangerous for Parole," AP News, 20 December 2024. (Accessed 21 April 2025); Tammy Webber and Dorany Pineda, "On LA Fire Lines, Inmates Shoulder Heavy Packs and Tackle Dangerous Work for Less than $30 a Day," AP News, 18 January 2025. (Accessed 21 April 2025).

- The banner for this exhibit, a photograph of incarcerated workerns on the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1885, is courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- The banner for the subheadings in this exhibit, a map of the Mountain Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad, ca. 1881, is courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_0_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)